Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Jul 04, 2019

Nowcasting Europe

- We introduce two new dynamic factor models to track economic performance in the UK and euro area

- Models provide unbiased, judgement free estimates of quarterly changes in economic growth

- Models rely heavily on PMI data as basis for creating business cycle proxies

In this research paper we build on our previous nowcasting work with Purchasing Managers' Index® (PMI®) data by introducing two dynamic factor models that can be used to provide judgement-free estimates of underlying changes in gross domestic product (GDP) for the eurozone and the United Kingdom.

Our research provides two key takeaways.

Firstly, a factor derived from a dataset covering a vast array of economic indicators, including business surveys, official figures and financial conditions data, is loaded heavily onto our own PMIs, reflective of the timeliness and close relationship that exists between the PMI data and changes in quarterly GDP.

Secondly, the derived factor can subsequently be used to calculate accurate and robust estimates of underlying GDP growth, providing unbiased, judgement-free estimates of economic performance in real-time.

Nowcasting: The Dynamic-Factor Model

Nowcasting, which is a process of measuring what's happening in the economy today, or in the very near past or future, has garnered an increasing amount of attention amongst policymakers, economists and investors in recent years. However, faced with an increasingly fast-paced economic environment, characterised by a large number of data sources of varying quality, volatility and timeliness, extracting a meaningful signal to track the economy in a timely fashion remains a demanding exercise.

Dynamic-factor models (DFM) can help in this regard. By extracting a single time-series "common-factor" from their datasets, modellers are able to capture and summarise a substantial proportion of the covariation between indicators. This factor can then be used as a proxy of the business cycle and, in turn, make judgement-free predictions about movements in gross domestic product (GDP), the most widely-used yardstick of changes in economic activity.

Crucially, the set-up of the statistical framework comfortably deals with the dual demands of non-synchronous releases and unavailability of lagging data sources e.g. industrial production, retail sales data. The ability of the model to fill in the dataset's so-called 'jagged edge' allows the maximisation of the information content held within timely, reliable indicators and allows the refinement of nowcasts in 'real-time' i.e. as and when data sources are refreshed and updated.

Here in the Economics Indices team at IHS Markit, we have followed the broad approach outlined above and constructed a model that produces DFM-based GDP nowcast estimates for both the euro area and the United Kingdom (UK).

Our nowcasting models utilise a variety of closely-watched indicators that are commonly used by economists to track the performance of these economies. The models cover various sectors of the economy by drawing on business surveys, official output data, labour market figures and information on financial conditions. A full list of the indicators used in each model is provided in the appendix.

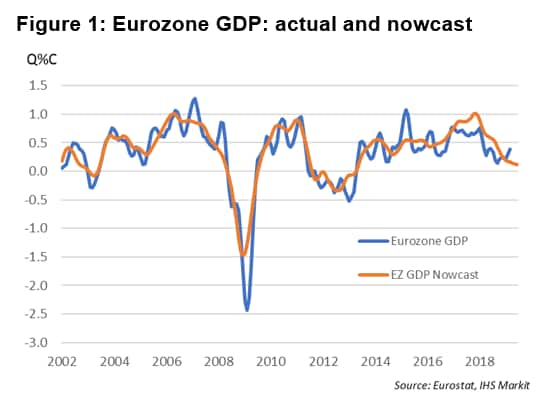

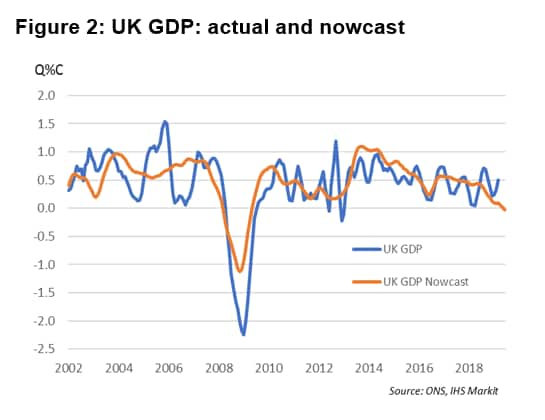

Our historical GDP nowcasters for the euro area and the UK are charted below against three-month-on-three-month changes in GDP. Note we have used our models to produce monthly estimates of official GDP growth between the official quarter end figures (ensuring we have a monthly time series to compare against).

In both instances, the GDP nowcasters line up well against GDP. For the eurozone, the correlation coefficient is 0.90 and for the UK 0.76. Some of the missing explanatory power partly reflects the smoother nature of our nowcasts: they tend to cut through some of the volatility exhibited in the GDP series, especially in the UK post-financial crisis era.

This is arguably a key feature of the dynamic-factor model: these models can provide solid estimates of the underlying performance of an economy, cutting through the noise of GDP figures which can be impacted greatly by one-off, idiosyncratic events that overly influence growth rates during a single quarter.

The strong build-up of inventories in the UK ahead of the (at the time) planned March 29th UK departure from the European Union (EU) is a topical example in this regard. Strong stock accumulation in the first quarter of 2019 arguably provided a "false" signal of the real position and health of the UK business cycle: Inventory positions will likely be unwound in the months ahead with the effect, all things being equal, of a lower UK growth profile.

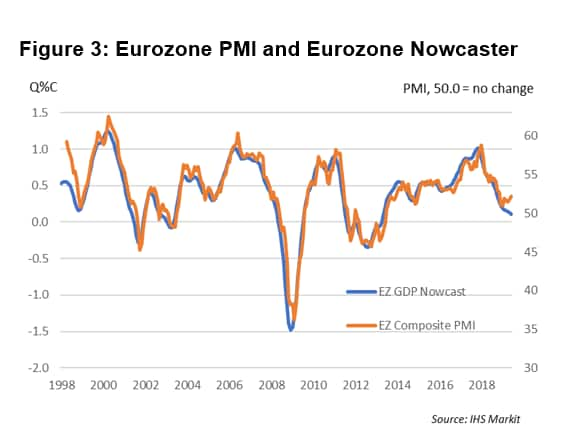

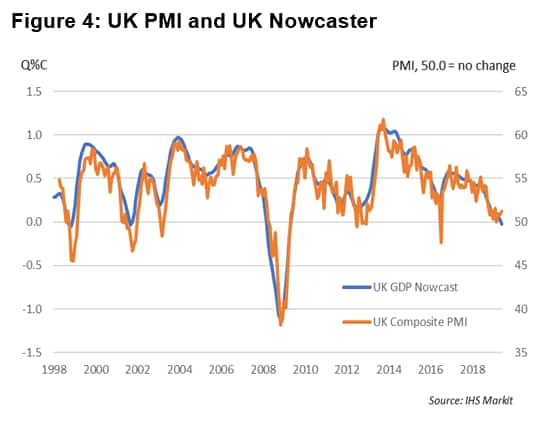

Notably, we find that the smoothness exhibited by the GDP nowcasters reflect the strong contributions made to the models by the respective Composite PMI data series. Given its timeliness, plus its own strong relationship with GDP data, the models lean heavily on the PMI and help to reduce the volatility seen in other series, such as industrial production, trade, retail sales figures etc.

Indeed, when tracked against each other, the nowcasters register correlations of 0.91 and 0.92 for the euro zone and the UK PMIs respectively. This indicates that PMIs are the best single source summaries of regional business cycle conditions (see figures 3 and 4).

Model Performance

We now turn to the short-term predictive power of the DFM models in anticipating quarterly changes in GDP.

Both of our models have been run in pseudo 'real-time' i.e. when making predictions about GDP growth we mimic the broad data structures that would have been available when the nowcasts are made.[1].

For instance, when making a prediction in early June about GDP growth for the second quarter of 2019, two months of business survey data related to activity over the quarter would be available. In contrast, there would be no information from official data sources such as industrial production figures.[2]

As data availability increases through a quarterly cycle, the nowcasts typically evolve. Our a priori expectations are that nowcast accuracy will improve in line with the dataflow i.e. the accuracy of the nowcast made just prior to the actual release of GDP data will be more accurate than those made at the start of a quarter when there is little or no data related to current economic activity available.

We have taken three distinct nowcast snapshots: the first just after the end of the first month of a quarter, the second around the midpoint of the nowcasting cycle, and the third just before the first release of GDP figures (when the data available is highest).

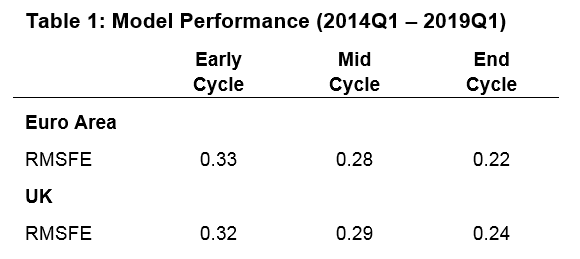

Table 1 provides a summary of the model performances for the euro area and the UK through a typical nowcasting cycle. Our out-of-sample exercise covers the period 2014Q1 to 2019Q1. The gauge of nowcast performance is the root mean square forecasting error (RMSFE). Readings closer to zero should be viewed as the most positive (i.e. containing the least error).

As expected, the RMSFE's generally improve through the nowcasting cycle, illustrating how the availability of high frequency data such as surveys and the flow of information are important in reducing error. From the early nowcast to the final nowcast, the gains in accuracy are 25% for the UK, and 32% for the euro area respectively.

The RMSFE readings of 0.20-0.25 at the end of the nowcasting cycle are also consistent with our reading of the academic literature in the post financial crisis period - and indicate sound model performance.

Where are we now?

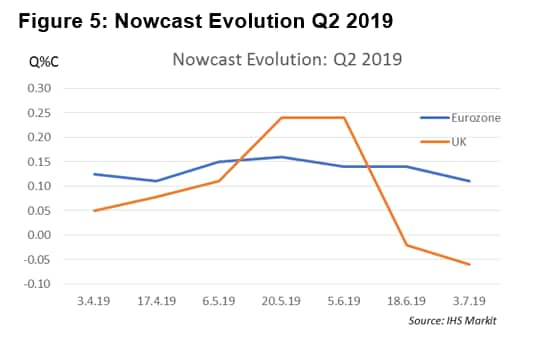

We have been running our models in real-time on a fortnightly basis since the turn of 2019. Here we discuss the latest nowcasts and their evolution over the second quarter of 2019.

The recent message from our nowcasters is not especially encouraging in terms of the health of the Eurozone and UK economies.

The euro area economy, characterised by global trade worries and political uncertainties, is set to register minimal growth at best in the second quarter of the year.

Underlying growth is estimated to be running at a quarterly rate of just 0.11%, a noticeable slowdown from the 0.4% increase seen during the first quarter, and amongst the softest rates of growth seen in the past six years - consistent with the recent messages from the timely PMI data.

The region's key German manufacturing base remains a particular source of weakness, with industrial production down by -1.9% on the month in April, whilst wider regional exports slid by -2.5%.

Eurozone growth therefore remains primarily dependent on private consumption, supported by the positive tailwinds of low unemployment and higher wage compensation. This is likely to help ensure further, albeit similarly subdued, GDP growth in the third quarter of the year. Our initial nowcast for Q3 2019 is for 0.18% q/q GDP expansion.

The picture is similar in the UK, albeit a little more volatile in terms of the growth profile following the strong boost to national output in the first quarter from Brexit-related stockpiling in the run-up to the original EU exit date of 29th March.

Following the release of poor April industrial output numbers (down -2.7% on the month) and trade data (exports down -2.0%, imports down -6.3%), plus ongoing PMI softness up to June, our nowcaster has been revised dramatically lower in recent weeks.

Indeed, the nowcast model suggests a slight contraction of the UK economy (-0.06%) in the second quarter of the year, whilst an initial nowcast for the third quarter points to economic stagnation (0.04%).

Although a little early to raise the possibility of a UK recession, if the newsflow continues to disappoint in the coming weeks the chances of such an outcome will inevitably rise.

Summary

In this research paper we introduced new nowcasting models to track economic growth in the eurozone and the UK. Drawing on a wide-variety of indicators to track economic performance, we found that these nowcasters leaned heavily on our own PMIs to provide reliable and timely estimates of growth.

Going forward, we plan to continue to update and communicate our nowcast results on a regular basis via our commentary webpage at www.ihsmarkit.com and historical data are available to subscribers on request. Any feedback from users is also welcomed.

Finally, we are also developing similar models for other large economies in Europe and around the globe. These will be introduced - and updated on a continuous basis - later in 2019.

Please click here for the full report

Paul Smith, Economics Director, IHS

Markit

Tel: +44 1491 461 038

Email: paul.smith@ihsmarkit.com

Joseph Hayes, Economist, IHS Markit

Tel: +44 1491 461 006

Email: joseph.hayes@ihsmarkit.com

[1] Note, however, that we stop short of replicating the data vintages that would have been available at the time, prior to subsequent revisions, due to difficulties in obtaining these data.

[2] We discussed the importance of timeliness in an economic indicator in our paper "Eurozone PMI and predicting economic growth. Please click here for full report.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fnowcasting-europe-040719.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fnowcasting-europe-040719.html&text=Nowcasting+Europe+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fnowcasting-europe-040719.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Nowcasting Europe | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fnowcasting-europe-040719.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Nowcasting+Europe+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fnowcasting-europe-040719.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}