Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Mar 14, 2018

Forgotten but not gone: NMRF proxies and the struggle for accurate QIS and capital efficiency under FRTB

The non-modellable risk factor (NMRF) requirements under the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB) continue to keep risk managers awake at night. With banks' trading operations already struggling to maintain profitability under high capital requirements from Basel III, firms are looking for strategies to mitigate punitive NMRF-related capital while also meeting the FRTB guidelines.

Since the Basel Committee first announced the FRTB requirements in 2016, we've been undertaking research on the impact of NMRFs and proxying. We've observed that most banks, despite participating in recurrent regulatory QIS (Quantitative Impact Studies), have little ability to assess the real impact of proxies on capital, given that their infrastructure is still largely configured for Basel 2.5 and existing prototypes do not necessarily provide an end-to-end view.

That is why we have designed our infrastructure to run "interactive capital studies" to measure the impact in IMA capital terms of switching NMRF data sources (for instance between internal transactions and pooled real price observations), as well as changing risk factor taxonomy or granularity (including approaches to risk factor bucketing) or even changing NMRF proxy selection methods.

These interactive capital studies have also helped banks assess the relationship between their own capital and proxies choices, as well as other subjective FRTB-related decisions. We've found that their understanding of the relationship between capital and desk structure, NMRF data sourcing and definition, or advocacy focus is approximative at best. Why are banks finding it so difficult to estimate the capital impact of such central IMA configuration decisions?

The complex nature of NMRF proxies

Proxies have been used by banks to substitute returns and back-fill historical data since risk models were first invented. NMRF proxies are, however, far more complex to implement and far more important to get right as they drive capital. Banks have to contend with the complexity of the actual ES calculations (up to 63 partial runs) and SES calculations. When introducing proxies, they also need to calculate the SES charge using a stress test applied to the basis between the original NMRF and its modellable substitute.

Depending on the proxy choice itself, banks may also add new (modellable) risk factors to ES which may impact PLA and back-testing. Needless to say, this requires more data when selecting proxies in a larger universe than the risk factors driving the actual portfolio. The data required to calculate the risk on the actual portfolio under FRTB will in turn be greater than Basel 2.5 as firms work to improve "risk coverage" to pass the PLA test.

Regulatory uncertainty is another key dimension which banks must grapple with. A good example is the debate triggered by the publication of the EBA discussion paper on 18 December 2017 which could impact both implementation and capital costs materially.

The benefits of getting proxying right

Given that NMRF proxies are so complex to implement, we have a dedicated stream of research on exploring their potential. It has led us to draw three main conclusions:

- Data pooling* can increase the modellability of risk factors and lead to capital reductions of as much as 40%. See our previously published research on the topic.

*Combining external real price observation data with a bank's existing, internal data sets - The use of proxies - where a risk factor is non-modellable - can deliver further capital savings

- The selection of the proxy methodology can have a significant impact on NMRF capital charges. According to our research, a statistical modelling approach to proxying produced a capital saving of 19% compared to a saving of just 11% for the simple, rules-based approach. See page 10 of the following document for more detail.

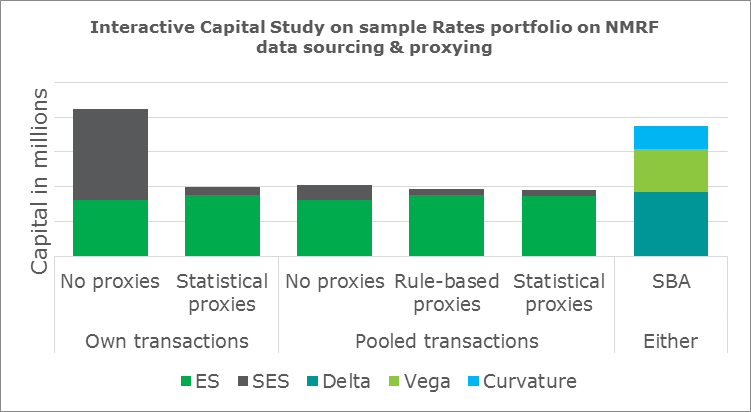

In one of our studies, we compared the impact of data pooling and proxying on the IMA capital charge of a sample rates portfolio. The findings were somewhat surprising in that the impact of pooling transaction data across multiple participants was not as significant as applying a sophisticated NMRF proxy approach on the un-pooled dataset. The chart below shows the results:

The statistical proxy technique shown in the second and fifth bars represents an upper limit to the capital saving achievable through proxying and may not be appropriate for all banks. However, the analysis illustrates that there are several routes available for banks to improve on the "risk sensitivity" of their proxies and hence improve the capital efficiency under the FRTB.

With Basel policymakers meeting recently to discuss possible revisions to the identification and capitalization of NMRF[1], there is still hope amongst risk managers that the NMRF framework will be softened. However, revisions are unlikely to be extensive, so banks should start looking for a Plan B. Carefully constructed proxies for NMRF are perhaps one underexplored area that has the potential to save the day.

This discussion has also glossed over the added complexity when tackling asset classes with inherent challenges under FRTB combined with poor liquidity, such as CDS, which we will cover in a later blog post.

Paul Jones, Global Head of Risk Utilities, Executive Director, Financial Risk Analytics at IHS Markit

[1] Risk.net, FRTB: banks grapple with hard-to-model risks, 9 February 2018

S&P Global provides industry-leading data, software and technology platforms and managed services to tackle some of the most difficult challenges in financial markets. We help our customers better understand complicated markets, reduce risk, operate more efficiently and comply with financial regulation.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fforgotten-but-not-gone-nmrf-proxies.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fforgotten-but-not-gone-nmrf-proxies.html&text=Forgotten+but+not+gone%3a+NMRF+proxies+and+the+struggle+for+accurate+QIS+and+capital+efficiency+under+FRTB+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fforgotten-but-not-gone-nmrf-proxies.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Forgotten but not gone: NMRF proxies and the struggle for accurate QIS and capital efficiency under FRTB | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fforgotten-but-not-gone-nmrf-proxies.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Forgotten+but+not+gone%3a+NMRF+proxies+and+the+struggle+for+accurate+QIS+and+capital+efficiency+under+FRTB+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fforgotten-but-not-gone-nmrf-proxies.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}