Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Jan 25, 2022

Flash PMIs signal sharp slowing in developed world growth at start of 2022 as Omicron wave hits

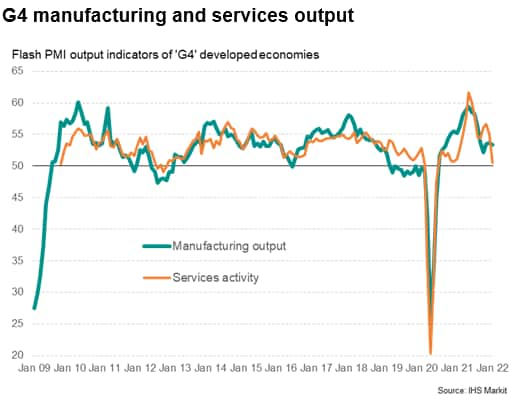

The pace of economic growth across the four largest developed economies slowed sharply in January to the lowest since June 2020 as the Omicron variant disrupted business activity. The impact was most fiercely felt in the service sector, with manufacturing supported by an easing of supply constraints. The reduced supply squeeze helped alleviate price pressures in manufacturing, but service sector charges spiked higher on rising energy and staff costs, pointing to still elevated levels of inflation in coming months. The outlook meanwhile remained one of heightened uncertainty, albeit with easing supply constraints helping boost prospects in the manufacturing sector.

Developed world growth slides to 19-month low

Flash PMI surveys for January signalled a sharp slowing in the pace of economic growth across the world's largest developed economies to the weakest since the recovery from the first lockdowns began in mid-2020. Growth in the 'G4' developed economies of the US, Eurozone, Japan and the UK had surged to an all-time high in May 2021 as economies opened up from pandemic-related restrictions, but growth subsequently slowed sharply as the demand recovery faded and the COVID-19 Delta wave further disrupted economies and supply chains. Another downshifting in the rate of expansion is now evident at the start of 2022 as the Omicron variant led to a further surge in virus infection rates.

Although new orders across the four largest developed economies continued to rise, the January increase was the weakest for nearly a year, in turn resulting in the smallest increase in companies' backlogs of work for ten months.

Measured across the G4 economies, the service sector was especially hard hit by Omicron, with activity slowing to near-stagnation, registering the weakest increase for 18 months. Manufacturing output growth slipped to the second-lowest in 17 months, but remained relatively resilient, buoyed in part by a further alleviation of supply constraints.

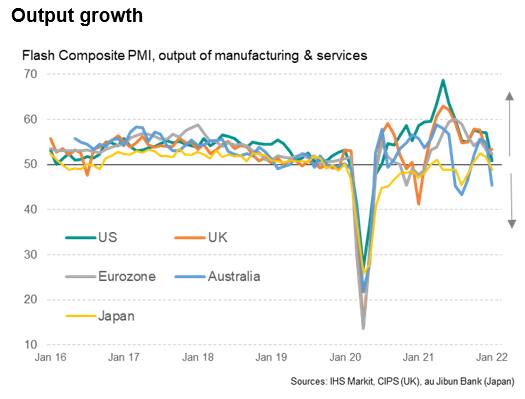

Japan and Australia contract, US stalls

The flare up of Omicron caused both Japan and Australia (the latter also covered by the flash PMIs) to fall back into decline, representing their third downturns so far during the pandemic. Both saw reduced service sector activity, with Australia's manufacturing economy also slipping into contraction. However, Japan's factory sector continued to expand, and at a solid rate.

The US meanwhile saw growth slow sharply to indicate a near-stalling of the economy, with both manufacturing and services reporting greatly weakened performances to record only very modest expansions during the month.

In Europe, Eurozone growth hit an 11-month low and growth in the UK continued to run at a rate similar to the 12-month low seen in December. Both economies battled against the Omicron variant, though with manufacturing output growth rates picking up amid fewer supply chain delays.

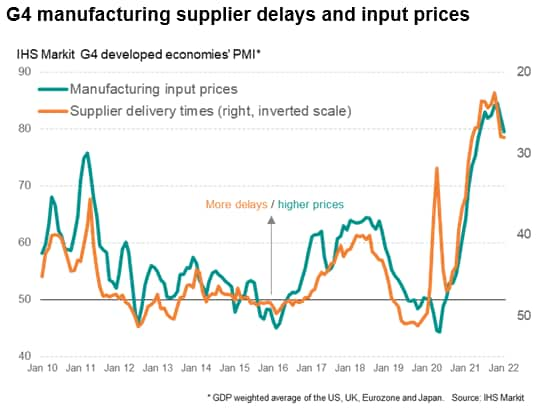

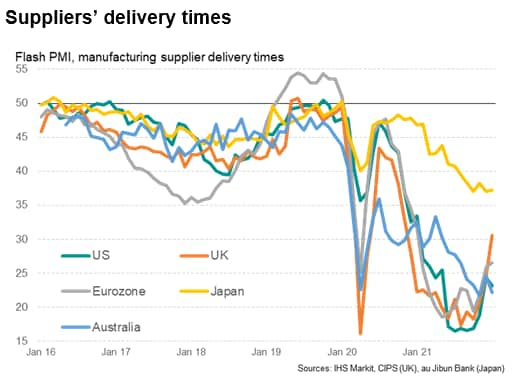

Supply constraints ease further record highs, though not in the US

One of the principal reasons for the relative resilience of manufacturing could in part be explained by spending switching from face-to-face services to goods as the Omicron wave took hold, but the factory sector also saw an easing of supply chain disruptions. Measured across the G4 economies in January, supplier delivery times continued to lengthen, but to the smallest degree since March of last year. The incidence of delays appears to have peaked back in October amid the Delta wave, and it has been encouraging to see delivery times not lengthen at an increased rate so far during the Omicron wave.

However, there are some notable regional differences in supply chains. While delivery delays in Europe eased considerably during January, delays worsened in the US, likely due to ongoing port congestion and other logistical issues which appear to be on the wane in Europe but still prove problematic in the US.

Varying sector price trends

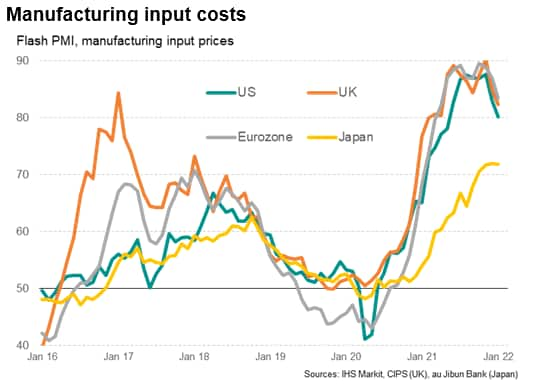

A welcome by-product of the broad easing in supply chain pressures was a cooling of input cost inflation, with raw material prices paid by manufacturers across the G4 economies showing the smallest monthly increase since last May. Notably, this easing in cost pressures included the US, despite the additional domestic supply chain pressure recorded during the month.

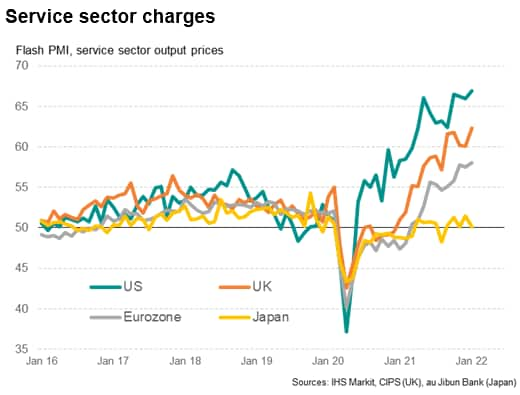

However, while producers' input cost inflation eased, average prices charged for services rose at a record rate across the G4 economies, with new highs recorded in the US, Eurozone and UK. Japan remained a striking exception, with charges barely rising.

Higher service charges were associated with soaring energy and staff costs, compounding supply and demand imbalances.

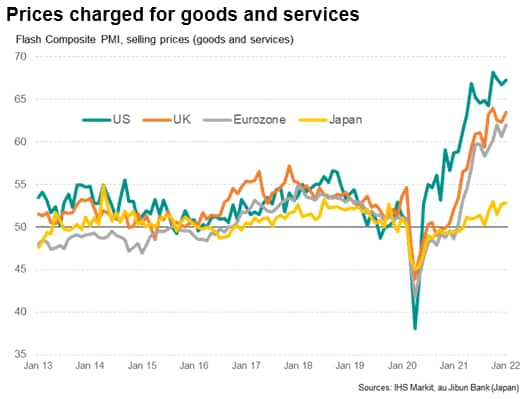

Average prices charged for goods and services consequently rose at increased rates in all G4 economies, running at or near record rates in all cases to hint at further sustained and elevated inflationary pressures.

Future expectations

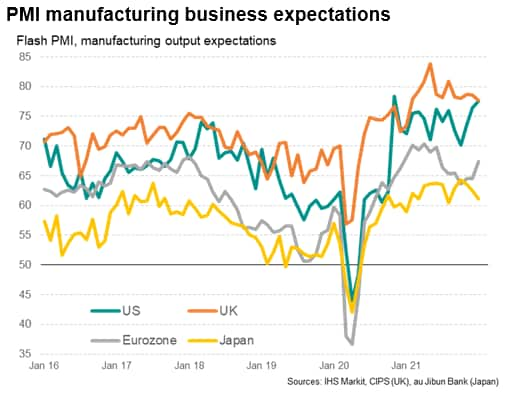

Looking ahead, hopes of alleviating supply shortages played a material role in lifting manufacturers' future output expectations higher in both the US and the Eurozone, albeit with optimism in the former limited by concerns over shipping delays. In the UK, improved prospects due to alleviating shortages were conflicted by concerns over the damaging effect of Brexit on trade with EU countries. In Japan, COVID-19 worries dominated, pushing expectations lower.

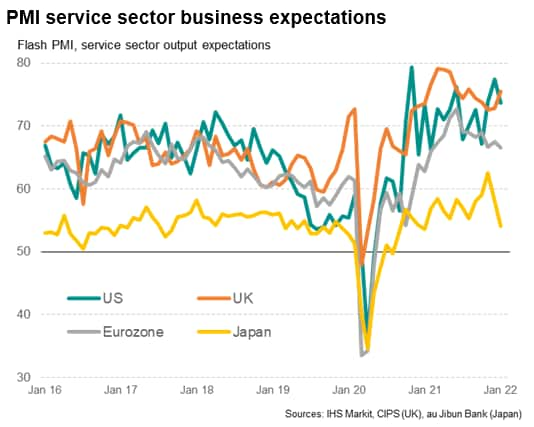

In the service sector, COVID-19 worries likewise pushed future activity expectations lower in Japan, the US and Eurozone, but prospects brightened in the UK. This likely reflects the timing of the Omicron wave, which hit the UK earlier than the other economies. UK firms consequently reported a brightening picture due to the imminent re-opening of the economy, but firms in other countries remained very uncertain either as to when restrictions will be lifted, or case numbers start to decline. Much will of course depend on how governments react to the Omicron wave, with the UK (and specifically England) appearing to be relatively relaxed regarding the health impact of the Omicron wave.

Outlook

When looking ahead, it is encouraging that demand - as measured by new orders - continued to rise at a stronger rate than output across the G4 economies in January, reflecting the ongoing constraints on output (namely supply chain delays and worker shortages due to the virus). Output growth could therefore reaccelerate, provided supply constraints continue to ease. We will therefore need to assess the broader supply situation out of Asia in January and February via the final PMIs to gauge extent of global supply constraints more fully.

As for demand, it's worth noting that, although the cooling of demand growth witnessed in January was in part attributable to the spread of the Omicron variant, the slowdown often coincided with reports of customers baulking at higher prices or having incomes squeezed by recent inflationary pressures, as well as fewer reports of companies building inventories.

Geopolitical concerns, notably in Ukraine, and the trend towards monetary and fiscal tightening that is widely anticipated in many economies - led by the US - in coming months is also likely to be detrimental to demand growth.

It is therefore possible that, while the global economy may be over the worst in terms of supply delays, these constraints are persisting (though not worsening) at a time during which demand growth is also waning, which points to risks being tilted towards a slower pace of economic expansion.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

© 2022, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole

or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fflash-pmis-signal-sharp-slowing-in-developed-world-growth-at-start-of-2022-as-omicron-wave-hits-Jan22.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fflash-pmis-signal-sharp-slowing-in-developed-world-growth-at-start-of-2022-as-omicron-wave-hits-Jan22.html&text=Flash+PMIs+signal+sharp+slowing+in+developed+world+growth+at+start+of+2022+as+Omicron+wave+hits+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fflash-pmis-signal-sharp-slowing-in-developed-world-growth-at-start-of-2022-as-omicron-wave-hits-Jan22.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Flash PMIs signal sharp slowing in developed world growth at start of 2022 as Omicron wave hits | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fflash-pmis-signal-sharp-slowing-in-developed-world-growth-at-start-of-2022-as-omicron-wave-hits-Jan22.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Flash+PMIs+signal+sharp+slowing+in+developed+world+growth+at+start+of+2022+as+Omicron+wave+hits+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fflash-pmis-signal-sharp-slowing-in-developed-world-growth-at-start-of-2022-as-omicron-wave-hits-Jan22.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}