Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Sep 24, 2021

Developed world economies hit by slower growth and rising prices

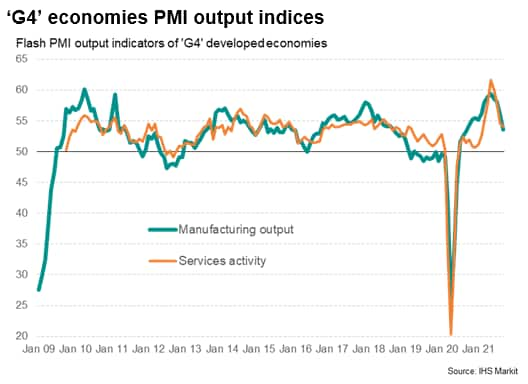

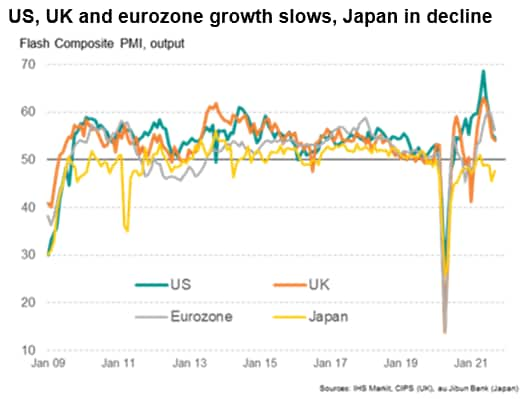

The rate of growth of the world's four largest developed economies deteriorated for a fourth month running in September, according to the flash PMIs. Growth slowed in the US, UK and Eurozone, while Japan remained in contraction for a fifth successive month. Price growth meanwhile accelerated to fall just shy of June's all-time high in the 11-year series history as costs rose at an unprecedented rate, linked in turn to growing material shortages and supply chain constraints.

These divergent output and inflation paths present a growing headache for central banks, though clearer trends should soon emerge.

Developed world growth weakens

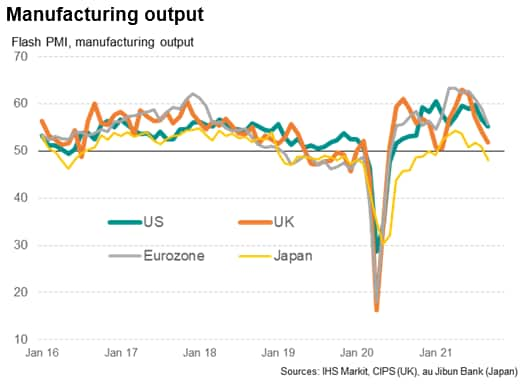

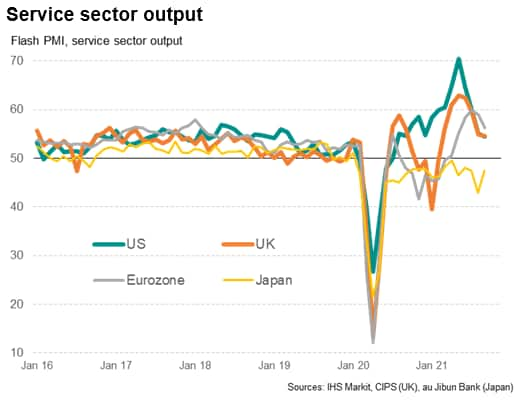

A weighted average of the output indices from the US, UK, Eurozone and Japanese flash PMI surveys showed business activity growing in September at the slowest rate since February. Across the four economies, manufacturing output growth slowed to the weakest seen over the past year while service sector growth hit the lowest since February.

Despite the falls, it should be noted that both sectors nevertheless remain in solid expansion territory, albeit with some marked variations around the world. Furthermore, the overall loss of momentum in September was the weakest seen over the past four months.

However, the PMI's forward-looking indicators such as new orders and future expectations lost further ground, hinting that growth is likely to continue to moderate in coming months.

Supply constraints hobble manufacturers

Manufacturing output growth slowed to a 10-month low in the Eurozone and an 11-month low in the US, though both considerably outperformed the UK, where growth likewise slowed sharply, and Japan, where the manufacturing sector fell back into decline for the first time since January.

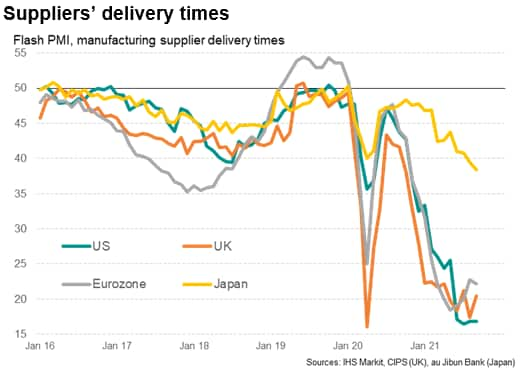

Producers in all economies saw a shortage of components and supply delays as a key factor behind the weakening manufacturing performance. On average, suppliers' delivery times lengthened across the four economies in September to an extent only exceeded by the deteriorations seen in June and July. The US reported the highest degree of supply chain lengthening, followed closely by the UK and the eurozone. While Japan saw relatively fewer delays, it was nevertheless the greatest lengthening recorded since the Fukushima incident in 2011.

In the UK, Brexit was also reported to have exacerbated the broader shortage-led slowdown.

Service sectors see weaker demand, and growing constraints

While service sector growth eased sharply to the lowest since May in the eurozone, even weaker expansions were recorded in the US and UK. The former saw growth slide to a 14-month low while the UK recorded the worst performance since January's lockdown. Japan meanwhile reported lower service sector output for a twentieth successive month, albeit with the rate of decline moderating.

Slower service sector expansions were linked to weaker demand, in turn often associated with disruptions due to COVID-19 infections and the spread of the Delta variant. Note that worldwide COVID-19 containment measures were tightened slightly during September, according to IHS Markit's tracking data, as governments including those of the US and Germany sought to control the spread of the Delta variant. In other countries, notably the UK, rising infection rates were often reported to have either quelled demand or disrupted businesses due to staff absences.

Staff shortages were also commonly reported to have hindered service sector and manufacturing growth in the US, adding to component supply issues.

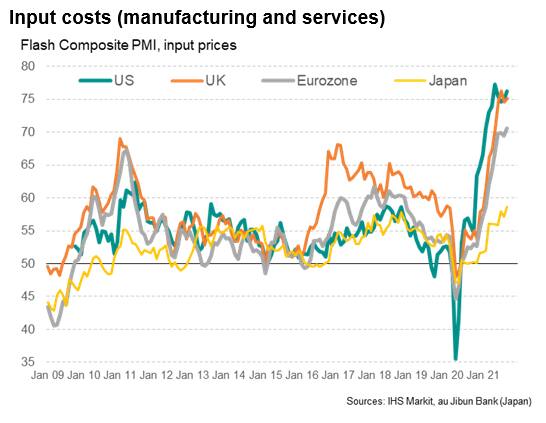

Prices rise across the board

A common thread in the September flash surveys was the feeding through of supply shortages, and in the cases of the US and UK, labour supply issues, in turn driving up prices. Average input costs rose at accelerated rates in all four major developed economies, rising close to almost regain recent all-time survey highs in the US and UK and climbing to a 21-year high in the eurozone. Even in Japan, input cost inflation accelerated to the fastest for 13 years.

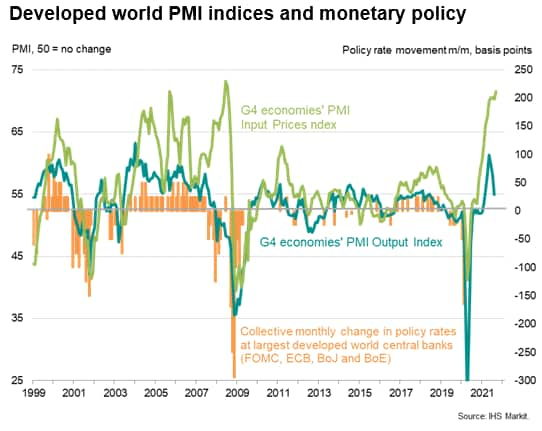

Policy headache

The divergence between the PMI signals of slower economic growth and steepening price pressures presents a dilemma for policymakers in the major central banks. While the price gauges fuel calls for policy accommodation to be scaled back, the deteriorating output momentum calls for caution.

Part of the dilemma is the assessment of the extent to which the current slowdown in output is a function of weaker demand or supply issues. Certainly the latter are causing some of the slowdown (for example, if an auto maker cannot produce cars due to a shortage of semiconductors, they are not going to be buying as many other inputs such as tyres, steel etc, and also not buying in as many industrial services). But it is unclear just how much of the slowdown reflects a softening of demand after the initial surge in spending as economies opened up once vaccine roll-outs reached successful stages. Let's not forget that the global economy looked far from healthy in the lead up to the pandemic. The global PMI came close to a decade-low back in October 2019, albeit picking up slightly as we moved into 2020.

For hawks, however, the additional concern is that it is also not clear how long the supply constraints will persist for. Each month of deteriorating supply not only adds to producer price pressures, but also adds to the likelihood of these higher prices feeding through to higher wages. Any material pick-up in such second-round inflation effects could mean inflation stays higher than central banks are currently envisaging.

The coming months of PMI data should therefore prove crucial in illuminating some of these trends, and hopefully pave a clearer path for policy.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

© 2021, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole

or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fdeveloped-world-economies-hit-by-slower-growth-and-rising-prices-sep21.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fdeveloped-world-economies-hit-by-slower-growth-and-rising-prices-sep21.html&text=Developed+world+economies+hit+by+slower+growth+and+rising+prices+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fdeveloped-world-economies-hit-by-slower-growth-and-rising-prices-sep21.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Developed world economies hit by slower growth and rising prices | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fdeveloped-world-economies-hit-by-slower-growth-and-rising-prices-sep21.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Developed+world+economies+hit+by+slower+growth+and+rising+prices+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fdeveloped-world-economies-hit-by-slower-growth-and-rising-prices-sep21.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}