Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

CREDIT COMMENTARY

May 31, 2018

CDS and redenomination

The spread volatility seen in recent days brings back memories of the 2010-2012 eurozone debt crisis. Whether they are fond recollections or not - many investors are no doubt scarred by the experience - in such febrile times observers from all asset classes reach for the CDS toolbox to try and gauge sovereign credit risk.

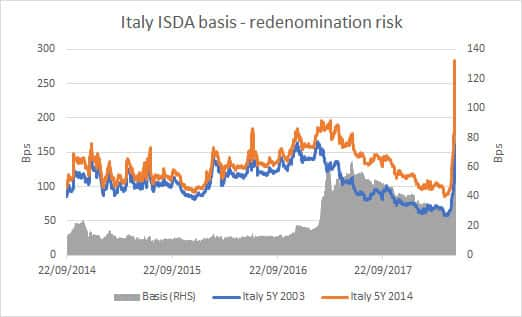

Since the eurozone crisis 1.0, however, there has been a significant change in how the CDS market operates. The ISDA 2014 definitions were introduced, and the resulting bifurcation in activity on sovereigns (as well as banks) means that spreads are quoted on both 2003 and 2014 definitions. The basis between the two spreads - often referred to as the ISDA basis - provides valuable market-derived information on the risk of a country leaving the eurozone. Some refer to this as the redenomination basis.

As this metric (covered in this column on several occasions) is now being looked at by non-credit specialists, it's worth revisiting what it really means. The 2003 definitions were drawn up in a time when the thought of a country leaving the eurozone and redenominating its debt was considered borderline unthinkable. Rates had converged, and member states could borrow money at very similar rates. Nonetheless, the possibility of redenomination is covered by the 2003 rules. Some press articles have asserted that redenomination wouldn't trigger 2003 CDS contracts - this is incorrect.

But the 2003 definitions do include some clauses that muddy the waters and possibly make it less likely that a redenomination would result in a credit event. In particular, this applies to G7 countries such as France, Germany and - most importantly - Italy. Section 4.7 (a)(v) of the 2003 rules define what is a Permitted Currency. If the currency of a debt obligation is changed to a non-permitted currency in a binding manner, then it would make it likely that a restructuring credit event would occur. But if the country in question is a G7 country (or an OECD country with a AAA rating) then the successor currency would still be permitted and therefore not trigger CDS. A deterioration in the creditworthiness of the reference entity would also have to be proved, as is the case for all restructuring credit events.

The ISDA 2014 definitions, on the other hand, were written after Greece had defaulted and the rest of the eurozone was rescued by Mario Draghi's "whatever it takes" stance. In short, a country leaving the eurozone was no longer unthinkable, regardless of its size. Hence the clause referring to G7 and AAA-rated OECD countries was removed and replaced by a broader definition. If a debt obligation is redenominated into a currency other than that of Canada, Japan, Switzerland, the UK, the US and the euro, then this could potentially trigger a restructuring credit event. Certain conditions still have to be met, crucially that an implied haircut (using a freely available market rate on the new currency) results from the redenomination.

To sum up the legal minutiae (a necessary evil of CDS), the 2014 definitions make a redenomination of debt from a currency leaving the eurozone more likely to trigger CDS. This is not as straightforward as it sometimes presented, as we have seen. But the basis between 2003 and 2014 spreads on eurozone sovereigns does indeed imply risk from renouncing the euro and subsequently redenominating obligations.

Italy's ISDA basis shot up from 30bps to 122bps over the course of the last month, with 50bps of the move coming in during the extremely volatile session of May 29. The 2014 five-year spread hit 284bps and the curve flattened, a sure indicator of credit deterioration and reminiscent of behaviour during the debt crisis (though still nowhere near the levels reached in 2011-2012). The basis has since recovered to less than 100bps amid talk that the nascent populist coalition can reach a compromise with the president and form a government. Italy leaving the eurozone is still an improbable scenario and would take a gargantuan effort from the government, a tough ask in a political system with checks and balances such as Italy's. But it can't be dismissed entirely and the CDS market, through the 2014 contract, is equipped to manage this risk.

S&P Global provides industry-leading data, software and technology platforms and managed services to tackle some of the most difficult challenges in financial markets. We help our customers better understand complicated markets, reduce risk, operate more efficiently and comply with financial regulation.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcds-redenomination.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcds-redenomination.html&text=CDS+and+redenomination+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcds-redenomination.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=CDS and redenomination | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcds-redenomination.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=CDS+and+redenomination+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcds-redenomination.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}