Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

CREDIT COMMENTARY

Aug 17, 2018

Banks and Turkish exposure - but don't forget Italy

Turkey's self-inflicted problems have had ramifications well beyond its borders and led to comparisons with previous emerging market crises. Mexico in 1994; south-east Asia in 1997; Russia in 1998; Argentina in 2001: all have been invoked as precursors to Turkey's seemingly inevitable descent into debt distress and recession.

But we are not there yet. Government mismanagement of monetary policy and deteriorating relations with the US exposed underlying weaknesses in the economy, and spreads remain beholden to the decisions of an unpredictable regime. The uncertainly is reflected in the inversion of the credit curve, where near-term default risk is higher than over a longer timeframe. But the government still has the tools to address market concerns, though whether it uses them is another matter.

Turkey's five-year spreads have partially recovered to dip under 500bps and we are yet to see the dreaded contagion. Argentina has also suffered a sharp fall in its currency, but unlike Turkey it has responded by hiking interest rates. Spreads are over 500bps but the curve shape is still positive. South Africa has also come under scrutiny and its spreads have widened from 180bps to 225bps during the recent turmoil - a significant move but nothing out of the ordinary. Tighter monetary policy in the US and Europe will test the weaker emerging market sovereigns over the coming months and years. However, it is not clear that Turkey will be the trigger for a decisive shift in risk appetite across the asset class.

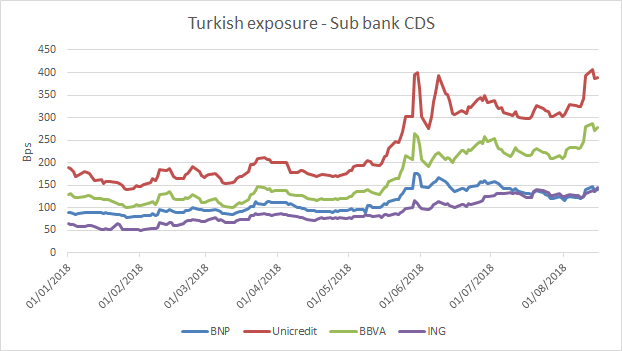

We know from the Great Financial Crisis that the banking sector is the true transmission mechanism for economic destruction. Could the exposure of European banks to Turkey result in a wave of credit deterioration engulfing the region? This seems unlikely when the financial statements of the exposed institutions are examined. BNP and ING both have a presence in Turkey but the size of their interests is relatively insignificant in the context of their balance sheets. This is reflected in the modest widening in their subordinated CDS levels.

BBVA has the biggest exposure through its 49% ownership of Turkish bank Garanti, which accounts for 13% group revenues. It's five-year subordinated CDS widened to 288bps, over 150bps wider than where they started the year. An increase in bad loans through a plummeting lira and Turkish recession would have an impact, but it seems manageable.

Source: IHS Markit Price Viewer for bonds

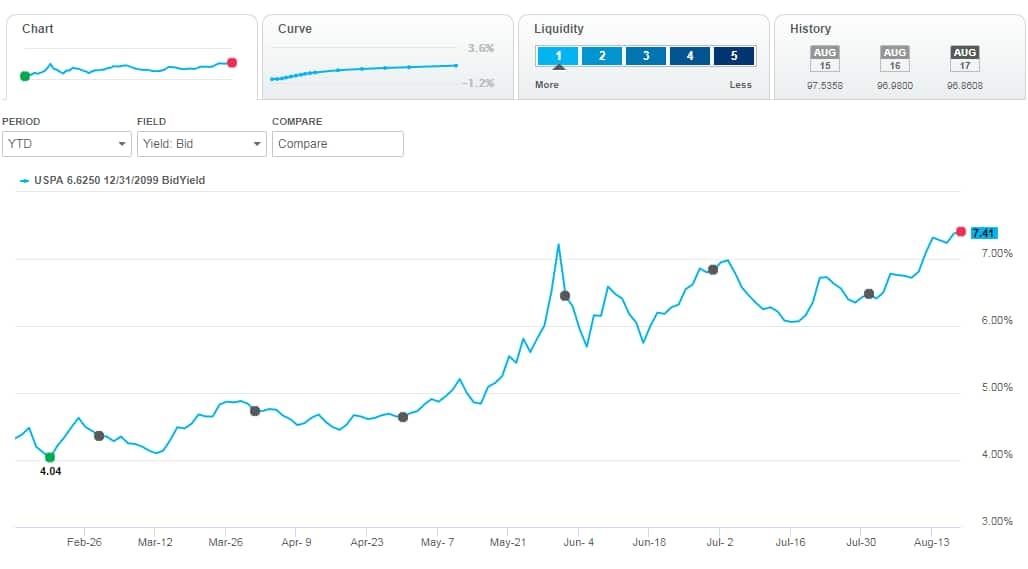

Unicredit has seen an even larger widening in subordinated spreads, a level of 406bps on August 13 marking the first time it has closed the day over 400bps since December 2016. The bank's AT1 bonds are yielding in excess of 7%, according to IHS Markit data. Its exposure to Turkey is relatively small compared to BBVA, so its underperformance seems striking. But the Italian bank is a major player in eastern Europe, a possible concern to some investors with risk rising in emerging markets.

Maybe just as important is the precarious state of Unicredit's home country. The new government is working on the budget for 2019, and it is still not clear how it will reconcile the populist spending policies that they have proposed with the fiscal rectitude demanded by the EU. The prime minister is making emollient noises about bringing the debt/GDP ratio down from its current 132%, but it seems inevitable that elements in the coalition will make pronouncements that cast doubt on this aim. Italian credits will no doubt experience volatility as a result, regardless of whether the Turkey crisis escalates.

S&P Global provides industry-leading data, software and technology platforms and managed services to tackle some of the most difficult challenges in financial markets. We help our customers better understand complicated markets, reduce risk, operate more efficiently and comply with financial regulation.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbanks-and-turkish-exposure-but-dont-forget-italy.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbanks-and-turkish-exposure-but-dont-forget-italy.html&text=Banks+and+Turkish+exposure+-+but+don%27t+forget+Italy+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbanks-and-turkish-exposure-but-dont-forget-italy.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Banks and Turkish exposure - but don't forget Italy | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbanks-and-turkish-exposure-but-dont-forget-italy.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Banks+and+Turkish+exposure+-+but+don%27t+forget+Italy+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbanks-and-turkish-exposure-but-dont-forget-italy.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}