Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Nov 26, 2020

Assessing the economic impact of escalating Australia-China trade frictions

- China-Australia trade tensions have escalated significantly during 2020, and IHS Markit's PMI data show Australia's exports slumping.

- With Australia exporting around one-third of its total exports to mainland China, there is a high degree of vulnerability to disruptions in bilateral trade. Recent developments have resulted in mounting concerns about the economic implications to the Australian economy from a protracted disruption of Australian exports to China.

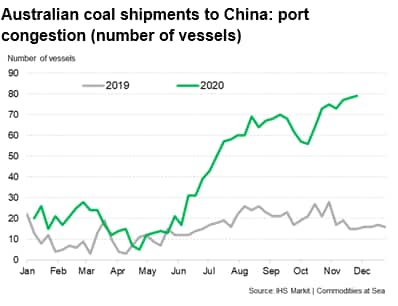

- Latest data from IHS Markit Commodities at Sea highlights the significant impact of bilateral trade frictions on Australian coal exports, with 76 bulk carriers loaded with Australian coal waiting at anchorage at the various Chinese ports. China's General Administration of Customs has also halted barley shipments from Australia since September 2020, while exports to China of a number of other products have also been impacted.

The escalation of trade tensions between China and Australia

Mainland China is the largest export market for Australia, accounting for 32.6% of total exports of goods and services in the 2018-2019 financial year. The importance of mainland China as an export market for Australia has increased dramatically over the past two decades, with Australian exports to mainland China having grown from AUD 8.8 billion in the 2000-01 financial year to AUD 153 billion in the 2018-19 financial year.

Consequently, Australia has become increasingly vulnerable to trade sanctions by China on its exports. Due to escalating frictions on a wide range of issues, bilateral trade tensions have increased significantly during 2020.

Total Australian exports of services to mainland China amounted to USD 18.5 billion in 2018-19, with education and tourism accounting for around 90 per cent of this total. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Australian exports of tourism and education services to China have largely come to a halt since April 2020 due to the strict travel bans by Australia on foreign visitors entering the country. Since Australian exports to China for both education and tourism have been severely disrupted due to the Covid-19 pandemic, this has removed any scope for trade policy action on these sectors, at least while the travel bans remain in place.

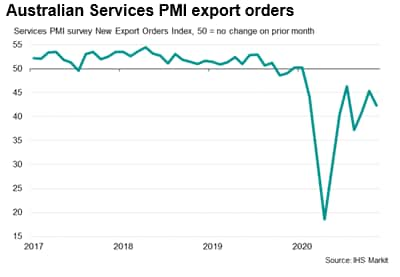

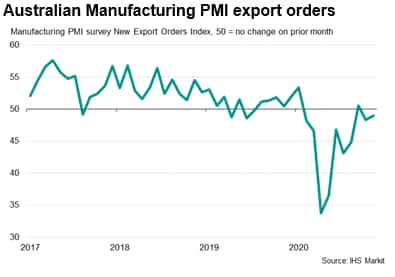

The economic shockwaves to Australia's service sector exports due to the pandemic are of course not limited just to exports to China. Total Australian services exports to all countries in September 2020 were down around 40% year-on-year, according to trade data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The latest flash IHS Markit Australian Services PMI reflects the continuing contractionary conditions that are impacting on Australia new export orders in the services industry.

However, Australian exports of goods have been impacted by an increasing array of trade policy actions by China. Even during 2019, there had been some temporary disruptions of Australian coal shipments to certain Chinese ports, with long delays in permission to unload Australian coal cargoes at Chinese ports.

In May 2020, the Chinese government also imposed punitive tariffs on Australian exports of barley to China, amounting to a combined 80.5% tariff on Australian barley, comprised of a 73.6% anti-dumping duty and a 6.9% countervailing duty. In September 2020, China's General Administration of Customs said barley shipments from Australia would be halted after they stated that pests were found on multiple occasions. Australian barley exports to China amounted to around AUD 1.4 billion per year prior to China's trade policy measures, with 70% of Australian barley exports having been shipped to China.

There has been a more intense escalation in trade measures by China in relation to Australian products since early November 2020. These measures, which include unofficial guidelines to Chinese importers as well as non-tariff measures such as customs procedures, have created considerable concern amongst Australian exporters of a wide range of products. The scope of the Chinese policy measures is reported to include beef, lobster and wine.

According to Chinese and international media reports, Chinese traders received an informal notice from authorities that Australian products in seven categories - barley, sugar, lobster, wine, timber, coal, and copper ore and concentrate - will not be cleared in customs from 6 November 2020.

However, the Chinese government denied any restrictions on Australian commodities. Amidst the confusion, there were reports that the Chinese end-users and traders are trying to resell their cargoes that have not reached Chinese ports and could cut down arrivals of Australian cargoes in the short term at least.

Australian total exports of goods to all countries were down 3% year-on-year in October 2020, with exports of coal down 27% and gas exports down 43% year-on-year. However, the overall contraction in exports has been mitigated by the continued strong performance of certain mineral commodity exports, notably metal ores, which rose 37% y/y in October 2020. This strong increase in metal ore exports has been helped by robust iron ore export volumes as well as buoyant iron ore prices throughout 2020. Meanwhile gold exports have benefited from the surge in world gold prices during 2020.

Due to the importance of iron ore in overall export values to mainland China, total Australian exports of goods to China actually increased by 13.3% y/y in October 2020, despite the various trade policy actions on a range of Australian exports during 2020.

Among the impacted export sectors, the Australian wine industry has seen rapid growth in exports to mainland China over the past decade, which reached AUD 1.2 billion in the year to September 2020, amounting to around 39% of total Australian wine exports. However Australian wine exports to China are reported to have faced severe customs clearance hurdles since early November. China's Ministry of Commerce announced on 18th August that it had launched an anti-dumping investigation into Australian wine. As a result, the Australian wine industry has reported that new shipments of wine to mainland China have been significantly curtailed while these hurdles to customs clearance continue.

Disruption of Australian coal exports to China

Australian coal shipments to China are also reported to have been delayed at Chinese ports.

According to IHS Markit's Commodities at Sea data, during 02-08 November 2020, no vessels laden with Australian coal vessels were discharged at the Chinese ports. In the last two and half weeks (09-24 November 2020) only nine vessels laden with Australian coal were discharged which is significantly below the normal levels analyzed in the past. As per IHS Markit shipping data, a total of 76 bulk carriers loaded with Australian coal are waiting at anchorage at various Chinese ports, with major congestion at Jingtang (22 vessels), Caofeidian (15 vessels), and Bayuquan (9 vessels). In terms of vessel segments, out of a total of 76 ships, 26 are Capesize vessels while the remaining 50 are Panamax vessel segments.

Due to the long queue, some vessels are also being diverted. For example, MV NAVIOS STELLAR (169,001 dwt) had loaded coal at Newcastle (sailed 5 October 2020) initially destined for Zhoushan; however, around 19 October 2020 got diverted to Krishnapatnam, India.

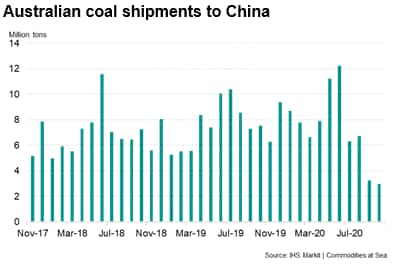

As a result of the severe disruption to Australian coal cargoes being shipped to China, latest IHS Markit Commodities at Sea data also shows that new loading of shipments of Australian coal cargoes destined for China have slumped in September and October, with weekly data also showing very weak coal shipments for China during November.

According to the McCloskey Coal Report (13th November 2020 edition) published by IHS Markit, Chinese buyers have been turning to the Atlantic market for replacement coal shipments due to the difficulties of customs clearance for Australian coal. Chinese buyers have been picking up numerous cargoes from South Africa and Colombia. In January-September 2020, Australia exported 74.9 mt of coal to China (41.1 mt of thermal, 33.6 mt of met coal), but by October 2020, monthly Australian coal shipments to China had fallen to a total of around 3 mt of both thermal and met coal, compared with 7.5 mt in the same month a year ago. In calendar 2019, Australia exported around 93 mt of coal to China.

Asia-Pacific Free Trade Agreements

Both China and Australia are members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) trade deal that was signed by 15 Asia-Pacific nations on 15th November 2020. The scope of RCEP includes reducing tariffs on trade in goods, as well as creating higher-quality rules for trade in services, including market access provisions for service sector suppliers from other RCEP countries. The RCEP agreement will also reduce non-tariff barriers to trade among member nations, such as customs and quarantine procedures as well as technical standards.

Nevertheless, the impact of this regional trade deal on reducing bilateral trade tensions between China and Australia has not yet been felt.

China and Australia also have in place the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement that entered into effect on 20th December 2015. This free trade agreement is due for a five-year review in December 2020, in the midst of significant turbulence in bilateral relations.

Outlook for Australia-China trade flows

A key weakness for Australia is that many of its major exports to China are agricultural and mineral commodities, many of which can be substituted by China for similar imports from other countries. Thermal as well as metallurgical coal is widely available from other global suppliers. China is willing to pay $115/t for USA mid-vol metallurgical coal versus cheaply available Australian mid-vol PHCC coal offered at $100/t which also had a freight advantage and short voyage journey.

While some Australian coal shipments can be diverted to other markets, China accounts for around 25 per cent of total Australian coal exports, amounting to around 100 mt per year, so it is extremely difficult to find alternative markets rapidly for such a large displacement of coal exports. However, over the medium term, Australian coal exporters had already recognized the need to develop their coal exports to other Asian markets such as India, Vietnam and Pakistan.

Similarly, agricultural commodities such as barley or beef can be bought by Chinese importers from other major agricultural exporting nations. As over 50 per cent of Australian barley exports had been sent to China in recent years, it will be difficult for Australian barley exporters to quickly find alternative markets for the entire displaced barley exports to China. However key international barley markets such as Saudi Arabia, India and Vietnam do offer some alternative market opportunities, and farmers will also shift production to other crops, mitigating the overall economic impact.

A particular challenge for Australia is that China is trying to meet its bilateral Phase One trade deal commitments to the US to ramp up imports of US goods. Consequently, substituting Australian agricultural exports for US exports would help China with its own commitments to the US under the US-China Phase One trade deal agreed in late 2019.

While a large share of total Australian exports to China, such as iron ore and LNG, have not been impacted so far by China's trade policy measures, there are intensifying concerns that an increasing range of Australian exports to China could face such measures.

Australian trade policy responses

Over the past decade, many Australian export industries had become increasingly vulnerable to disruptions of market access to China due to rising concentration risk to that single market. This had become well recognized as a key risk by Australian policymakers and industry leaders in recent years. However, as the former Citibank CEO Charles Prince was quoted as saying in 2007 prior to the Global Financial Crisis in relation to the leveraged lending business, "As long as the music is playing, you've got to get up and dance". The music has certainly stopped for a number of Australia's significant exports to China.

While Australia is unlikely to embark on any kind of tit-for-tat retaliatory trade measures, particularly given the very asymmetric bilateral trade relationship, the policy implications for Australia are that most Australian export industries with significant exports to mainland China will be urgently looking at diversification strategies to reduce their vulnerability to future Chinese trade policy measures. It seems clear that any hopes of a return to "business as usual" have become a rapidly receding mirage.

However, the process of trade diversification for various industries is likely to be gradual, over a protracted period of time, as different industries look to diversify into a wider range of export markets.

Despite the tremendous challenges of significantly diversifying its export markets, Australia will benefit from its proximity to many other large consumer markets across the Asia-Pacific region. India is already the world's fifth largest economy, with its consumer market forecast to grow strongly over the next decade. The ASEAN region has also become a very large consumer market with a total regional GDP of USD 3 trillion and a population of over 600 million. Consequently, ASEAN and India are likely to be high priorities for Australia's export diversification strategy over the decade ahead.

Rajiv Biswas, Asia Pacific Chief Economist, IHS Markit

Rajiv.biswas@ihsmarkit.com

Rahul Kapoor, Vice President, Maritime & Trade, IHS Markit

Rahul.kapoor@ihsmarkit.com

© 2020, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole

or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fassessing-the-economic-impact-escalating-australiachina-trade-frictions-nov2020.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fassessing-the-economic-impact-escalating-australiachina-trade-frictions-nov2020.html&text=Assessing+the+economic+impact+of+escalating+Australia-China+trade+frictions+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fassessing-the-economic-impact-escalating-australiachina-trade-frictions-nov2020.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Assessing the economic impact of escalating Australia-China trade frictions | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fassessing-the-economic-impact-escalating-australiachina-trade-frictions-nov2020.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Assessing+the+economic+impact+of+escalating+Australia-China+trade+frictions+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fassessing-the-economic-impact-escalating-australiachina-trade-frictions-nov2020.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}