Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

May 19, 2015

UK falls into deflation, but falling prices look set to be short-lived

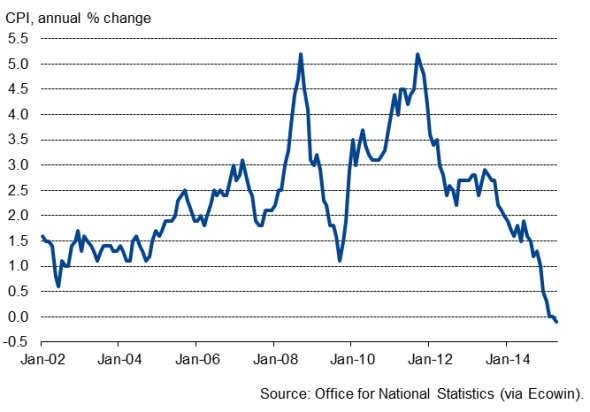

Deflation has hit the UK, but looks unlikely to stay for long. Consumer prices were 0.1% lower than a year ago in April. The government's number crunchers reckon this is the lowest since 1960. It's certainly the lowest since the existing index was first compiled in 1989, according to the Office for National Statistics.

Consumer prices

The ongoing lack of inflation is a boon for consumers, acting as a welcome surrogate for wage growth which, although showing signs of rising, remains subdued. Alongside falling unemployment, low prices, especially for fuel, have boosted consumer spending, providing the main thrust to economic growth at the moment. The so-called 'Misery Index', which combines inflation and unemployment data to provide a barometer of household woe, is currently at an all-time low (data were first available in 1989). However, there's an inherent danger here, as PMI surveys showed economic growth all-too dependent on the consumer-oriented service sector in April, with growth rates slowing sharply in both manufacturing and construction.

Prices to perk up

Further weak inflation numbers are expected in coming months, but deflation is likely to be short lived, and the UK shows few signs of sinking into a Japanese-style deflationary slump. The inflation rate looks set to start picking up later this year, largely in response to the price of oil, and could easily move back into positive territory as early as May due to the fact that April's numbers were driven lower by the timing of the Easter holidays (which pushed up last year's travel prices but did not affect this year's calculation).

There is far greater uncertainty, however, as to the extent to which inflation may take off, with important implications for both economic growth and interest rates.

A small uplift in inflation wouldn't be a bad thing, as it removes the threat of a deflationary mind-set becoming entrenched. At the moment, falling prices are boosting consumer spending and economic growth. But this won't last forever: if prices continue to fall, there is a danger than people will start deferring purchases in the hope of lower prices in the future.

A small uptick in the inflation rate also merely puts the Bank of England on a steady course of gradual interest rate increases.

A more marked upturn in inflation is the bigger worry, as this would not only subdue consumer spending, removing the main driver of current economic growth, but also push the Bank of England into a more aggressive policy tightening.

How worried should we be?

It's not hard to see why the Bank of England is warning that "inflation should pick up notably" towards the end of 2015.

The oil price is 40% cheaper than a year ago so far in May, but even if the price merely stabilises at around $65 per barrel it will be rising in year-on-year terms by the end of 2015, exerting upward pressure on inflation.

There is also the possibility of global food prices picking up sharply later this year as harvests look set to be disrupted by a stronger than usual El Ni"o.

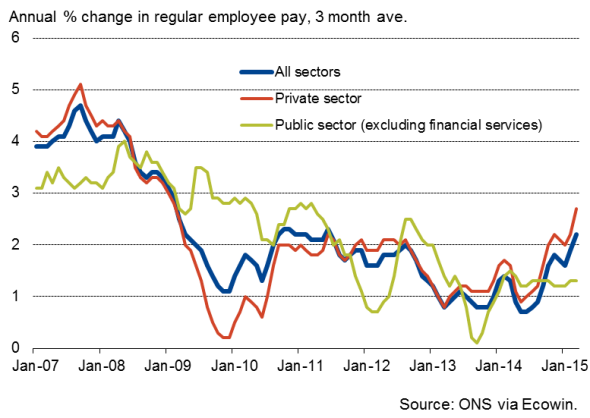

Wage growth also appears to be reviving as the labour market tightens, meaning companies will seek to charge more for their goods and services to protect margins. Consumers will meanwhile become less price conscious. The latest official data showed private sector employee earnings rising at the fastest rate since early-2009 after stripping out bonuses, up 2.7% on a year ago. With unemployment continuing to fall and companies still recruiting in healthy numbers, wage growth could well pick up further in coming months.

Wage growth

On the other hand, retail competition remains intense, especially among the supermarkets, and wage growth is far from rates that tend to worry policymakers. There are also signs that low inflation is feeding through to weak annual salary reviews, which may cap future pay growth this year. Finally, global economic growth remains subdued, which should help keep a lid on oil prices. In any event, if the economy slows, the Bank of England may once again choose to "look through" any upturn in inflation caused by oil and food prices.

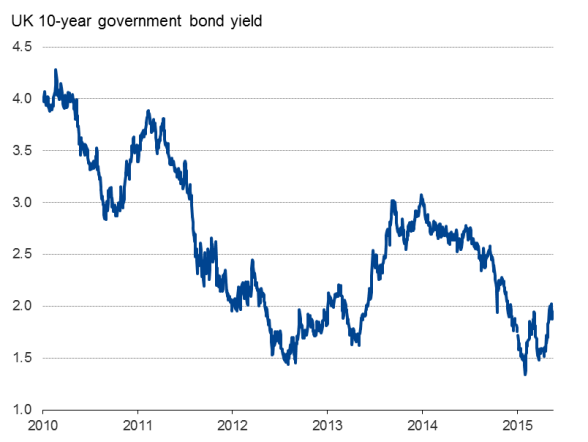

Bond market hit

While a strong lift-off in inflation is therefore by no means definite, it certainly seems that the threat of deflation has been overplayed, which is likely to be one of the reasons that fixed-income markets are being hit (higher inflation effectively reducing the real return of these investments). The yield on 10-year UK government bonds (which move inversely to price) has risen to around 2% as markets price in higher future inflation. Yields remain historically low though, as the most likely scenario is one of inflation picking up only moderately, leaving interest rate hikes to also be delayed until late this year at the earliest, and to then rise only gradually.

Source: Markit.

Chris Williamson | Chief Business Economist, IHS Markit

Tel: +44 20 7260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f19052015-Economics-UK-falls-into-deflation-but-falling-prices-look-set-to-be-short-lived.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f19052015-Economics-UK-falls-into-deflation-but-falling-prices-look-set-to-be-short-lived.html&text=UK+falls+into+deflation%2c+but+falling+prices+look+set+to+be+short-lived","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f19052015-Economics-UK-falls-into-deflation-but-falling-prices-look-set-to-be-short-lived.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=UK falls into deflation, but falling prices look set to be short-lived&body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f19052015-Economics-UK-falls-into-deflation-but-falling-prices-look-set-to-be-short-lived.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=UK+falls+into+deflation%2c+but+falling+prices+look+set+to+be+short-lived http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f19052015-Economics-UK-falls-into-deflation-but-falling-prices-look-set-to-be-short-lived.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}