Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

CREDIT COMMENTARY

Mar 09, 2015

A new era for senior debt

The Austrian government's decision to suspend payments on Heta's senior bonds may be a sign of things to come for European banks.

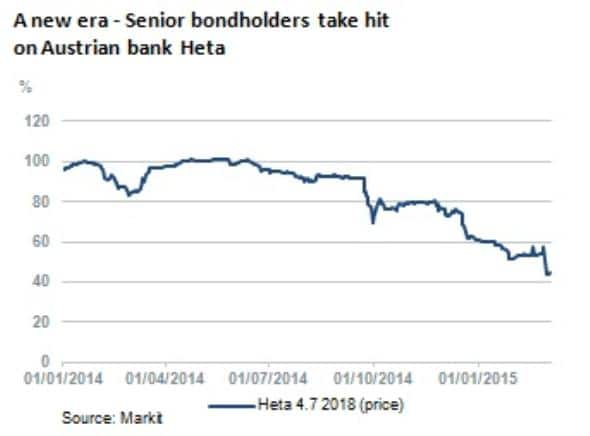

- Heta's bonds dropped sharply following the moratorium

- Little sign of effects on the broader European banking sector

- But Austria's approach will become the norm after the EU's Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive is implemented next year

When it comes to how banks finance their activities, there is little doubt we are in a new era. If anyone did question that the climate has changed, then a little-known Austrian institution may have caused them to think again this week.

The government of Austria announced that Heta Asset Resolution, the "bad bank" that resulted from the restructuring of failed Hypo Group Alde Adria, would no longer make principal and interest payments on its senior bonds. Austria took this action after it was revealed that Heta had a €7.6bn capital shortfall. Unsurprisingly, the price of the bank's senior bonds dropped dramatically - the 2018 paper fell from 58 to 44.

Although Heta is a minnow in the European financial system, the moratorium on the bond payments has implications for banks across the continent. Austria was an early adopter of the EU's Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) last month, and this is the first example of how the new rules will affect banks.

Senior bonds were considered sacrosanct during the banking crisis, as the taxpayers of Ireland know all too well. But from January 1st 2016 the BRRD will be implemented across all EU states, and investors will have to be aware that it is not just subordinated debt that can be bailed-in by governments.

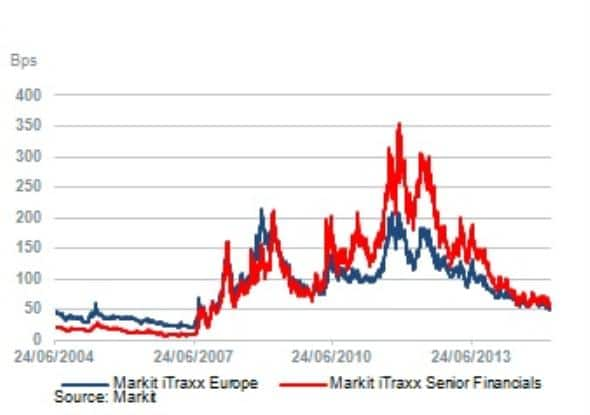

The news from Austria had a negligible impact on the broader market. The Markit iTraxx Senior Financials index widened 2bps to 56.8bps, but by Friday news that the ECB was launching its QE programme on March 9th led to the index rallying to 53bps. Perhaps Heta's diminutive size caused the markets to disregard its travails.

But the BRRD will surely have an impact on the cost of capital for European banks, and this will have to be taken into account. Pre-crisis, banks could raise funds at an artificially low level thanks to the implicit support from governments - they are too big to fail. With the pain of banks bailouts still being felt, taxpayers are no longer so generous. Bondholders will have to fill the breach.

This could push credit spreads on senior bank debt wider. But the more stringent capital requirements are arguably positive for bondholders as they strengthen balance sheets (equity investors won't enjoy the benefits). This means that the relationship between bank credit and the broader corporate markets - demonstrated by the basis between the Markit iTraxx Europe and the Senior Financials - is not straightforward, and it is far from certain that the latter index will dip below the former, as it did last year and was the norm before the crisis struck.

Gavan Nolan | Director, Fixed Income Pricing, IHS Markit

Tel: +44 20 7260 2232

gavan.nolan@ihsmarkit.com

S&P Global provides industry-leading data, software and technology platforms and managed services to tackle some of the most difficult challenges in financial markets. We help our customers better understand complicated markets, reduce risk, operate more efficiently and comply with financial regulation.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f09032015-Credit-A-new-era-for-senior-debt.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f09032015-Credit-A-new-era-for-senior-debt.html&text=A+new+era+for+senior+debt","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f09032015-Credit-A-new-era-for-senior-debt.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=A new era for senior debt&body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f09032015-Credit-A-new-era-for-senior-debt.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=A+new+era+for+senior+debt http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f09032015-Credit-A-new-era-for-senior-debt.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}