World economic growth is expected to accelerate gradually in 2014, largely as a result of easing private-sector deleveraging and government austerity in developed economies. But risks loom that could yet derail the fragile recovery.

Global economic conditions are expected to improve modestly in the year ahead, as markets continue their bumpy rebound from the Great Recession. A somewhat mixed forecast will see slowed growth in emerging markets, including China, partially offsetting the gains expected in developed economies such as the US. However, a number of risks loom that, if realized, could yet dim the global economic outlook.

Potential concerns include an oil supply disruption and accompanying price spike; inflation rates approaching deflation in the developed world; and further reductions in capital expenditures. In addition to these known risks, there are also unforeseeable ones, such as those that have emerged in the wake of Russia's March intervention in Ukraine. The manifestation of any of these risks as a full-blown crisis could well trim global economic growth prospects for 2014 and beyond.

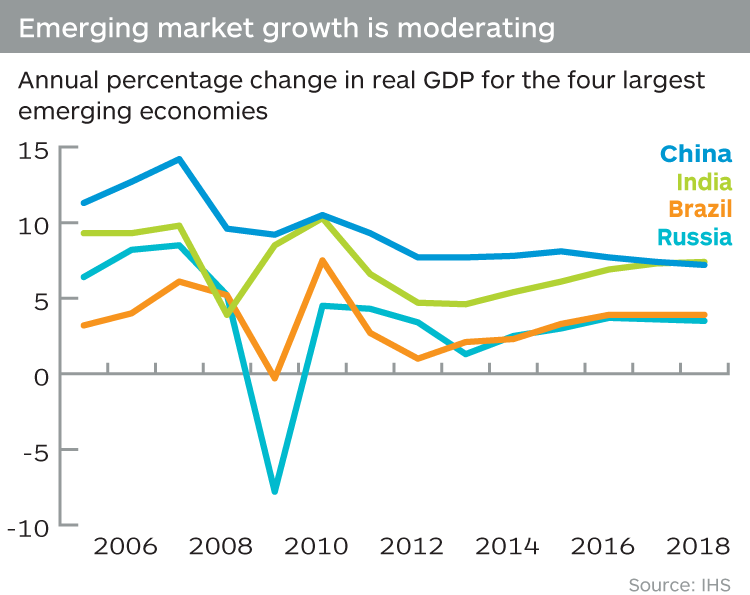

The good news is that global growth is expected to accelerate to 3.2% in 2014 up from 2.5% last year, and the world economy will finally shrug off its two-year stagnation. The irony is that the new locomotives of growth will be the advanced economies, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and possibly Japan. Meanwhile, average growth in the emerging markets, which fell from 7.3% in 2010 to 4.7% in 2013, will continue to disappoint in 2014. In the coming year, emerging markets will contribute the least amount to global growth since 2010, while advanced economies will see their strongest growth in four years, according to S&P Global estimates.(See figure below.)

Notwithstanding this cautiously optimistic assessment, there are multiple risks that could bring about another year of sluggish growth—or possibly worse.

Corporate caution in the developed world

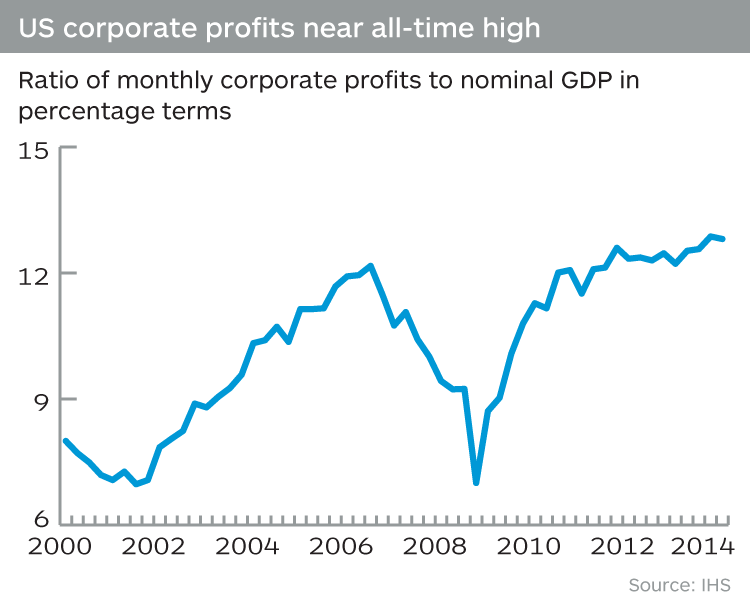

One of the unusual and troubling characteristics of the current business cycle has been the disconnect between profits and capital expenditures (capex). Profits and corporate cash as a percentage of GDP are at or near record highs in the developed world, whereas spending by businesses on physical capital has been extremely anemic. Lackluster topline growth and uncertainty about policy have been the major culprits.(See figure below.)

Since the end of the Great Recession, corporate profits as a percentage of GDP have risen in most of the world's advanced economies. This is not a new trend, but the continuation of a trend that has been in place since the mid-1980s. There are many reasons for the rise in relative profits. The principal long-term, structural driving force has been the plunge in the cost of computing, thanks to rapid advances in information technology which, in turn, have reduced the price of capital relative to labor. This trend has been reinforced by the fall in the effective corporate tax rate and the steady decline in borrowing costs over the past three decades in the developed world, with the notable exception of Southern Europe. To finance the shift from labor to capital, companies have boosted their profits and savings.

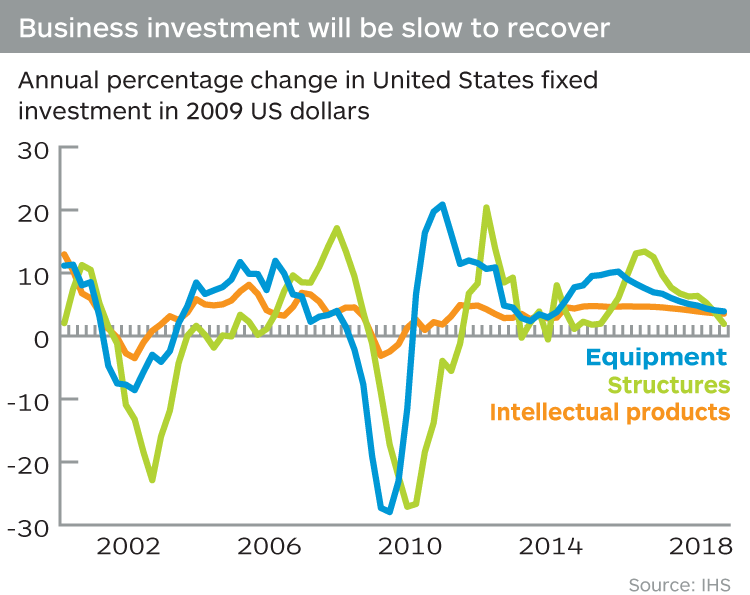

In stark contrast, real gross private nonresidential investment (non-housing capex) is barely above its 2007 peak in the United States and well below its peak in much of Europe. In past economic cycles, this strong growth in profits would have triggered a sharp rebound in capex.(See figure below.)

There are five key reasons why this time is different. First, weak top-line growth and worries about the sustainability of the recovery are major factors. Massive public- and private-sector deleveraging has been a big drag on growth in the developed world. This has made companies extremely cautious. The sharp rise in profits has been almost entirely due to their laser-like focus on cost cutting and productivity improvements.

Second, the severe lack of credit availability in the past few years has made the financing of capex a major challenge and reinforced business risk aversion. This is a particularly big risk in Europe now.

Third, these trends have been more pronounced among publicly traded companies than privately held ones. For example, capex is approximately 7% of the total assets of private companies, versus 4% for listed companies. For obvious reasons, the latter are more focused on earnings per share than are the former. This can reinforce the bias in favor of cost cutting and efficiency over risky investments with longer-run payoffs.

Fourth, policy uncertainty has been a major factor in the current capex cycle. The toxic budget debates in Washington and the lack of clarity regarding which taxes might be raised and which programs might be cut have made strategic planning by corporations extremely difficult. Similarly, the protracted sovereign debt crisis in Europe has made businesses extremely risk averse.

Lastly, the regulatory environment has also become more onerous. Since 2009, the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation and the Affordable Care Act (along with other regulatory changes) in the United States have raised corporate anxiety with respect to both their design and implementation. In Europe, the complex and sometimes contradictory energy and environmental policies have hurt competitiveness and become major headwinds for European businesses.

Threat of secular stagnation

Corporate caution has raised the specter of "secular stagnation," a concept that dates back to Karl Marx, who asserted that overproduction in capitalist societies would drive down the rate of return on capital and thus bankrupt the system. This concept was revived by Harvard economist Alvin Hansen in the 1930s. Hansen, a disciple of John Maynard Keynes, worried that too much saving and too little investment would lead to a permanent slump, the only cure for which was more aggressive fiscal stimulus.

Recently, some economists (notably Lawrence Summers of Harvard and Paul Krugman of Princeton) have taken up the banner of secular stagnation again. These new "stagnationists" worry that with short-term interest rates at the "zero lower bound," central banks have no room to maneuver. Moreover, with rates of inflation falling in the developed world and dangerously close to deflation, real interest rates are rising—further depressing capital spending.

Fortunately, the hypothesis of secular stagnation is belied by recent US data. Many of the trends that have worried analysts and policymakers in recent years—low rates of household formation, depressed birth rates, low levels of capital spending relative to GDP, and large numbers of long-term unemployed workers—have recovered and are on track to attain pre-recession levels in the next few years. Still, if US corporations retreat back into their shells, then another period of subpar growth cannot be ruled out.

Arguably, secular stagnation was a more apt description of Japan's economic circumstances until a year ago, when the government of Shinzo Abe began a series of aggressive stimulative policies. Until then, Japan's economy had suffered through two lost decades and persistent deflation. Part of the problem was the unwillingness of the Bank of Japan to expand its balance sheet and the monetary base. "Abenomics" has changed all that, with inflation rising and real interest rates falling over the past year.

A mild form of secular stagnation is also likely afflicting parts of Europe—especially in the south. Compared with the United States, Eurozone banks are less well capitalized, home prices in several key economies, including France, have only just begun to fall, and the demographic and growth outlooks are much less favorable. All of this hurts the prospects for capital spending. Just as crucial, the European Central Bank (ECB) has fallen "behind the curve." After expanding the monetary base from 2010 to 2011, the ECB has allowed this essential tool in its monetary arsenal to contract. This means that the risk of deflation in the Eurozone is higher than in the United States.

A lot will depend on what policymakers do next. In the case of Japan, Abenomics needs to "stay the course" to ensure that the improved economic prospects and easing deflationary pressures are a permanent part of the economic landscape. In Europe, where secular stagnation is a bigger risk, the burden is on the ECB to expand the monetary base again—aggressively—and prevent a dangerous drift into deflation. The United States probably has the easiest challenge. Given that the risks of secular stagnation are relatively low, the need for more fiscal stimulus is difficult to justify. By the same token, as the economy is beginning to show signs of life, any further austerity would be highly counter-productive. The implications for the Federal Reserve are also relatively straightforward. The decision to begin a gradual tapering of its bond purchases seems to be justified in light of improving economic conditions. But it is one thing for the Fed to take its foot off the accelerator in a measured way and another to step on the brakes. The latter should not—and likely will not—happen until there is further evidence a sustained recovery is in place and the risks of deflation are fading.

China's shadow banks pose a big risk

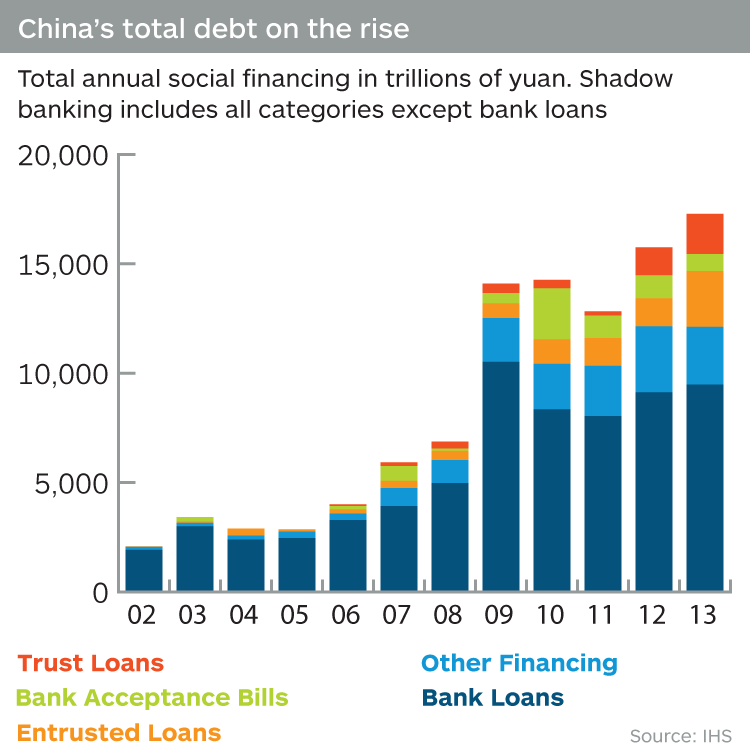

The proliferation of shadow banking activities in China continues to pose systemic risk and, as such, is set to become a key political priority in 2014 and beyond. A recent near-default case involving a CNY3 billion shadow banking product issued by China Credit Trust clearly illustrates the inherent risks and underlying interconnectedness within China's financial system. Rescue for the near-bankrupt fund stands at odds with authorities' increasingly clear preference to grant market forces a more decisive role in the economy. While recognizing some justifications for the bailout, including higher pre-holiday market volatility and the pending release of new shadow banking regulations, S&P Global considers this event a missed opportunity for the authorities to have shown clear commitment to restraining a prominent moral hazard and bringing shadow banking under greater control. Although there appears to be a general consensus favoring financial sector liberalization, the demand for cheap credit from powerful state-owned enterprises and well-connected local governments threatens to slow or block reform. Lower economic growth increases the latent risk from shadow banking while exacerbating the very high overall level of credit risk within China's financial system.(See figure below.)

Prior banking/debt crises in China have shaved about one-third off real growth rates over a five-year period relative to the prior five-year period. By a rough definition that would include 2009 or 2010 onward as a debt "crisis," Chinese GDP growth over a five-year period could drop by another 1 to 2.5 percentage points if the current banking/debt crisis deepens considerably. Single-year drops could be more dramatic, which could have serious ramifications for global growth.

Renewed emerging markets crisis

The fragile predicament of emerging markets came into sharp focus again in the early months of 2014. Weaker-than-expected data on the Chinese economy, expectations of further tapering by the Federal Reserve, and continuing fears about the precarious finances of some emerging markets caused a run on the Argentine peso, which in the end Argentina's government chose not to fight. The following week, Turkey was forced to raise short-term interest rates massively in an effort to halt the run on its currency. At roughly the same time, the central banks of India and South Africa also raised rates. Most of these countries now face stagflation—very weak growth and rising inflationary pressures—which is being exacerbated by market pressures and central bank actions.

The good news is that a repeat of the 1997–98 emerging-markets crisis is unlikely. The fragilities seem to be specific to a relatively limited group of countries, and there does not seem to be a systemic problem. Compared with the earlier episode, most countries have more flexible exchange rates, larger foreign exchange reserves, and healthier banks. Meanwhile, countries such as China, Mexico, South Korea, and Taiwan have not been hurt much by the recent market turmoil.

The bigger problem for the big emerging economies, including China, is that after having enjoyed a boom in the decade of the 2000s, there has been an alarming deceleration in the past four years. This has little to do with the "taper panic" that gripped financial markets in the spring and summer of 2013; the more daunting challenges facing most emerging markets are structural. The "BRICs party" of the 2000s was fueled by three global drivers: a credit boom, a commodities "super cycle" propelled in large part by China's double-digit growth rates, and "hyper-globalization" as multinational corporations expanded global supply chains.

All three of these drivers have lost their steam, leaving many emerging markets high and dry. Meanwhile, most of these economies enjoyed the boom without putting in place the structural reforms that would have improved their productivity, raised their competitiveness, and guaranteed a strong long-term trend in GDP growth. In fact, potential GDP in the emerging world is now growing at barely half the rate that it grew in the mid-2000s. Without major microeconomic reforms that would open up labor and product markets, reduce fiscal burdens, and lower unit labor costs as a result of productivity gains, a return to the "BRICs party" of the 2000s is unlikely.

Supply disruptions and the risk of an oil shock

Ongoing supply outages and the fear of further political instability in major producing countries are counteracting downward price pressure from the uncertain economic climate—especially in emerging markets—and the ongoing US tight oil production boom.

Geopolitical risk—especially within OPEC—will continue to preoccupy the market, as about 3 million barrels per day (mbd) of crude remains off the market. In Libya, the seizure of infrastructure by regional and tribal groups continues to shut in more than 1 mbd of production. In Venezuela, antigovernment protests underscore the risk that the country's economic and political climate will deteriorate further, possibly turning its production profile from sideways to downward. Talks for a final nuclear accord with Iran will be a tough slog. Meanwhile, Iran's oil production and exports are unlikely to increase appreciably. In Iraq, looming elections, political uncertainty and rising violence could disrupt the oil sector. Finally, renewed fighting in South Sudan threatens oil output. These and other factors suggest that any further disruption in oil supplies could begin to push oil prices back up again, threatening global growth.

And then there is Ukraine

The ouster of the pro-Russian president of Ukraine earlier this year and the subsequent annexation of Crimea by Russia have precipitated a geopolitical crisis not seen since the end of the cold war. S&P Global analysts assess that the most likely outcome of this crisis is a sustained standoff or a "frozen conflict"—a scenario in which Russia remains in control of Crimea but makes no further territorial incursions into Ukraine. This means that existing US and EU sanctions will remain in place, but there will be no further tougher measures. If, on the other hand, Russia does invade parts of Eastern Ukraine (motivated perhaps by clashes between ethnic Russians and Ukrainian nationals) then much tougher sanctions are likely to be implemented.

Ukraine's economy was already in very bad shape before this crisis, because of serious mismanagement. However, recent promises of aid from the International Monetary Fund and closer trade links to the European Union will likely provide some relief, though probably not enough to prevent a deep recession for Ukraine this year.

Arguably, the biggest economic loser from this crisis—even in a "frozen conflict" scenario—is Russia itself. Its economic growth last year was an already weak 1.3%. Investor sentiment towards Russia had already turned very sour, in large part because of Russian resource nationalism. And even though Russia has a current account surplus, its currency was hammered along with those of other emerging markets last spring and summer during the so-called "taper panic."

Russia's recent actions have exacerbated an already bad economic situation. The ruble is now one of the hardest hit currencies, as more investors have fled the market; stock prices have dropped precipitously; inflationary pressures are rising; and the central bank has been forced to raise interest rates. The crisis has also galvanized Western Europe to reduce its reliance on Russian natural gas—which currently supplies 30% of consumption—though such a shift will take time. This is very bad news for Russia, because natural gas exports account of about 40% of its total exports.

If the crisis escalates and Western sanctions become tougher, then the impact on the Russian economy could become quite severe, pushing it into recession. In such a scenario, European growth would also be hurt, which would be an unwelcome risk to the global economy.