Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Blog — 8 Sep, 2022

Introduction

The Black Hat Conference recently celebrated its silver anniversary, having been spun off of DEF CON 25 years ago as an attempt at a more professional information exchange between security researchers and those interested in the information security space. That original purpose was reflected in the conference's first name, Black Hat Briefings, with "black hat" being a moniker for an actor that abuses computer systems for malicious reasons. This year's event hit on familiar themes, including bemoaning the security product space — an increasingly tenuous position with a full expo hall just outside, but speakers must play to an audience of beleaguered security professionals. However, 2022 also has unique challenges, and keynote talks by former Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) director Chris Krebs, journalist Kim Zetter, and conference founder Jeff Moss focused on issues of cyberoperations between countries, the role of government, the elevation of the individual and small teams, and protection of critical infrastructure.

The Take

Moss opened the conference with a discussion of the "super empowered" individual or small group. His past example was pointing out the degree to which the internet once depended on BIND and DNS software, and the degree to which BIND itself relied on maintainer Paul Vixie. He noted the Spamhaus spam block list and the degree to which it is leveraged by email providers, giving that organization outsized influence in blocking email. He then turned to the current conflict in Ukraine, noting two specific examples: Nominet suspending services for Russian domain registrars and MongoDB Inc. (NoSQL database) terminating user accounts and databases from Russia and Belarus.

While organizations can choose where and where not do business, this scale of sanction has historically been the domain of governments. The internet's dependency on tools or code maintained by small groups suggests that those same individuals or small groups will exercise greater influence in both current and future geopolitical conflicts, even to the point where debates are occurring within these maintainer communities on how to sanction more precisely. The most obvious corollary beyond tools and services is the near total dependence on open-source code in modern applications.

Key points of the keynotes

Moss and Krebs offered complementary outlooks for the future. The former's focus on "outsized influences" spoke to both the good and bad of the new asymmetrical landscape. Krebs, in turn, focused on broader policy changes that were based on nimbler organizations to reflect the new threat landscape. For the U.S. to respond better to threats in privacy, safety and trust, he cited the Reorganization Act of 1939 as a precedent to reorganize. Changing the way government works – by not necessarily going with the lowest-cost providers, or by focusing solely on checklists and freeing up CISA from under the Department of Homeland Security – might offer a faster security focus for both the U.S. government and its public policies. The complementary outlooks from Krebs and Moss reflected the stoic philosophy for individuals and organizations to "control what they can control." Organizations may have difficulty predicting the exact timing, likelihood and severity of a potential Chinese invasion of Taiwan, but they can and should begin to plan for disruptions. Krebs noted that after the invasion of Ukraine, organizations made decisions to de-platform CIS/Russia quickly and sometimes without fully understanding the harm to civilians. Last, Krebs and others have mentioned the idea of governance and regulations to be based on outcomes rather than "checklists." In this transition, industry regulation has shifted from singular, point-in-time checks to more continuous assessments over time. PCI-DSS 4.0, released in March, is the latest framework that increases audit frequency and a more disciplined and deliberate assessment. While checklists have frequently been criticized for their lack of relevance regarding security outcomes, it is perhaps better argued that checklists need to be constantly revised to achieve better outcomes.

The conflict in Ukraine and "cyberwar"

Following on Moss' commentary about the outsized influence of individuals or small groups with respect to the conflict in Ukraine, one of the more well-attended talks presented compiled research from a variety of sources at security vendors that cataloged the various known cyberattacks on both sides of the conflict and their intended or actual effects. Probably most well-known is the April attack on Ukraine's energy suppliers, an attempt to cause a blackout, and not the first, which probably led to the improved response to this attempt. This conflict has employed data-wiping malware, or wipers, to an extent not yet seen. Part of that past reluctance to use wipers makes sense as a strategy. Wipers do exactly what one might imagine they do – destroy data – but they also burn the previously gained access of attackers, which has an opportunity cost. As most espionage operations rely on an attacker quietly maintaining access once gained, wipers are a very different kind of strategy. The script instances themselves and the techniques used to deploy them are examples of using a minimum viable product in a much more targeted scope than prior efforts, very different than 2017's NotPetya, which seemed to overrun its target, causing significant collateral damage.

Black Hat also included a surprise visit from Victor Zhora, the deputy director of Ukraine's State Service of Special Communications and Information Protection, who noted an exponential increase in cyber incidents. Zhora did not mince words when describing the unprecedented cyber operations occurring during this conflict, calling them "cyberwar crimes." A debate continues within the industry as to what types of attackers or combination of attacks, or additional context classifies something as cyberwar, separate from espionage and hacktivism, and what the downstream effects might be, including other countries observing this as an example and increasing their investments in critical infrastructure protection.

Black Hat is (mostly) commercial

While there is no shortage of important security research that is revealed at Black Hat and DEF CON, it was only a matter of time before Black Hat became mostly commercial – sponsored by and for vendors. Black Hat's schedule reflects these changes, with 99 non-sponsored briefings and 97 sponsored sessions. This increased commercialization reflects the continued industry lift from its grassroots origins to a more mainstream security conference.

Long registration lines

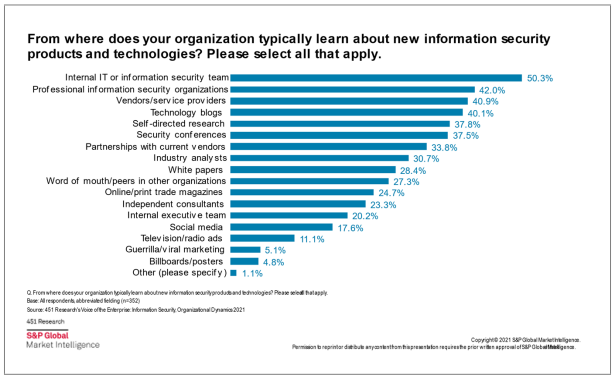

While official attendance numbers are not yet available, the secondary anecdotal indicators of a long-snaking registration line and packed sessions seem to indicate at least a beginning of a return to form for the large security conferences. Despite its origin as a slightly more professionally wrapped DEF CON, Black Hat has emerged as one of the major commercial infosec conferences alongside the RSA Conference in San Francisco. The return of in-person conferencing as vaccine rollouts and other mitigations of the pandemic take hold isn't entirely unexpected – as Figure 1 shows below, enterprise security managers consistently rate conferences as one of the main ways they find out about innovation in the security product or services space once beyond self-directed research. A major question for the Black Hat Conference will be what aspects of virtual conferences to pull forward as in-person conferencing returns. The availability of on-demand video released shortly after a talk, for example, is a feature that is carrying over from the COVID-19-induced virtual conference era that allows even in-person conference attendees to miss a session and still virtually attend it later. Moving this closer to real time will allow conference participants both onsite and remote to experience a talk at the same time. While there is some resistance to this idea as onsite tickets are an important part of the revenue model for conferences, since organizers are less interested in disincentivizing onsite attendance, it is not clear from the in-person attendance that this effect would be realized.

Figure 1: Sources of Information on Security Product or Service Innovation

Source: 451 Research's Voice of the Enterprise: Information Security, Organizational Dynamics 2021