Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ARTICLES & REPORTS — Nov 14, 2023

by Christoph M. Puetter and Stefano Renzitti

Let us consider a slightly hypothetical but instructive case study. A bank and a counterparty enter an uncleared over-the-counter trade agreement. They regularly exchange variation (VM) and initial margin (IM) to mitigate counterparty credit risk [1]. Assume the bank has a credit rating of A and the counterparty a credit rating of BBB or lower. Suppose also that when the counterparty defaults, a significant exposure gap suddenly opens to the detriment of the bank, causing a large loss. In principle, IM is designed to protect against such gap risk, but it does so only to a certain extent. The questions are then: How much protection does IM provide in severe or highly idiosyncratic circumstances where default and close-out are best described by jump-at-default dynamics? And how cost-efficient is the (regulated) IM when considering its impact on both counterparty credit risk and funding costs?

The tight adverse interaction between the default and market risk factors just described is the hallmark of systemic wrong-way risk and is often only deemed relevant when dealing with a highly rated, systemically important counterparty. In this article, however, we relax this assumption and allow the counterparty to be less important and its credit rating to be less than stellar for two reasons. For one, doing so helps to clarify the role and impact of IM in a jump-at-default wrong-way risk setting. And for another, applying jump-at-default wrong-way risk dynamics to a lower rated counterparty seems also plausible and realistic, albeit atypical. For example, when dealing with a highly leveraged and highly concentrated counterparty, a forced liquidation of positions upon counterparty default within a short time frame can incur sudden and large close-out losses for a bank. Recall the events and losses associated with the demise of Archegos Capital Management in March 2021, which was assigned an internal credit rating that fluctuated between BB and B prior to the default by one of the surviving banks (the now resolving Credit Suisse, which itself held an external credit rating of A at the beginning of 2021) [2].

Counterparty credit exposure is conditional on default and represents the residual exposure at close-out after accounting for all available margin (VM and IM). Risk measures that characterize this exposure are the credit valuation adjustment (CVA) when seen from the bank's perspective and the debit valuation adjustment (DVA) when viewed from the counterparty's angle. Any exposure and/or collateral exchange prior to default also needs to be funded. Their costs are summarized as funding valuation adjustment (FVA) for uncollateralized exposures, collateral valuation adjustment (CollVA) for VM, and margin valuation adjustment (MVA) for the bank's IM (assuming symmetric credit support). Applying a shareholder-centric valuation adjustment framework that avoids DVA/FVA double counting and ignores capital valuation adjustment, the total valuation adjustment amounts to [3, 4]:

We can simplify this expression further when we assume that VM is always exchanged and collateral optionality is insignificant or nonexistent (in that we discount at the collateral rate). As a result, FVA and CollVA vanish, and only CVA and MVA components remain:

These components behave differently under different default dynamics. The CVA term is highly sensitive to wrong-way risk jumps that occur at default or over the course of the close-out. The MVA term, on the other hand, is completely insensitive to the default dynamics. To get a better grasp of the behaviors, we compare below two distinct types of dynamics: (a) portfolio and collateral evolve diffusively without jumps over the close-out period, and (b) portfolio and collateral evolve diffusively with jumps over the close-out period. In the latter case, the jumps are driven by default-conditional discontinuities in the underlying risk factor evolution. For details on jump-at-default exposure modeling, see Puetter and Renzitti, 2023 [5].

As examples, the portfolios examined here align with the single-trade portfolios presented in Puetter and Renzitti, 2023 [5]. They consist of a 10-year USD interest rate swap, a 10-year resetting JPY/USD basis swap, and a 10-year non-resetting JPY/USD basis swap (initially all at-the-money). Assume that collateral for the interest rate swap and the cross-currency basis swaps is exchanged solely in the form of 10-year T-bonds and JPY cash, respectively. For the sake of argument, and out of convenience, suppose further that the risk factor jumps are modelled such that they are consistent with a 10% drop in the value of a 10-year T-bond for the interest rate swap case and a 30% drop in the JPY/USD exchange rate for the cross-currency basis swap cases (as estimated in Chung and Gregory, 2019 [6]). Finally, imagine that the annualized spread for funding IM is 1% and the bank's credit rating is A. Our simulations then produce the results shown in Tables 1-3.[1]

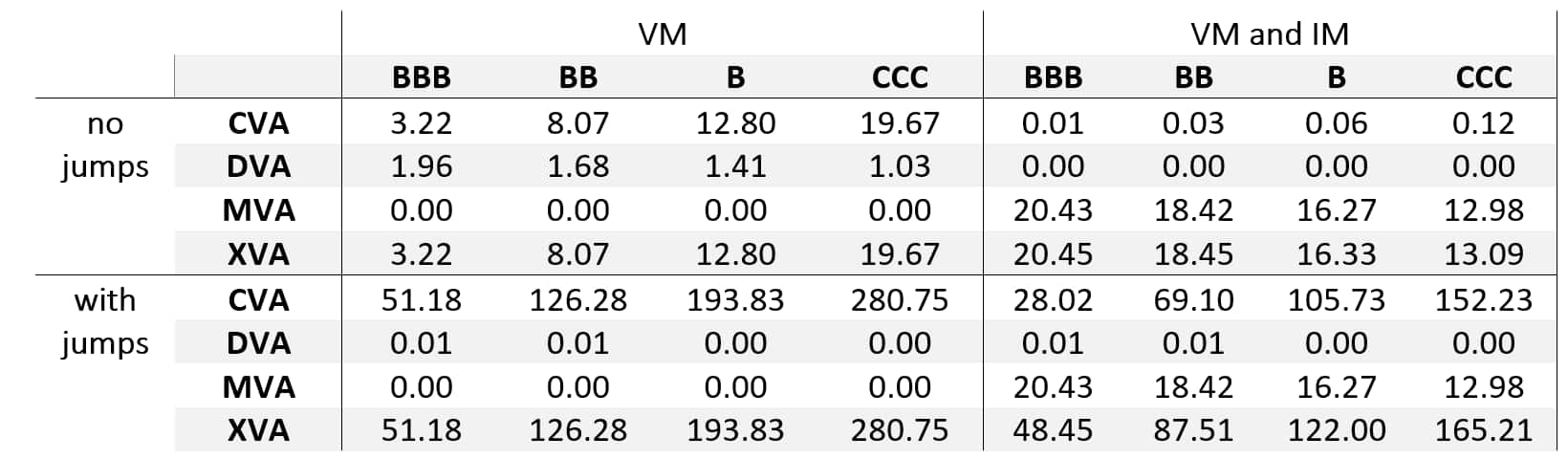

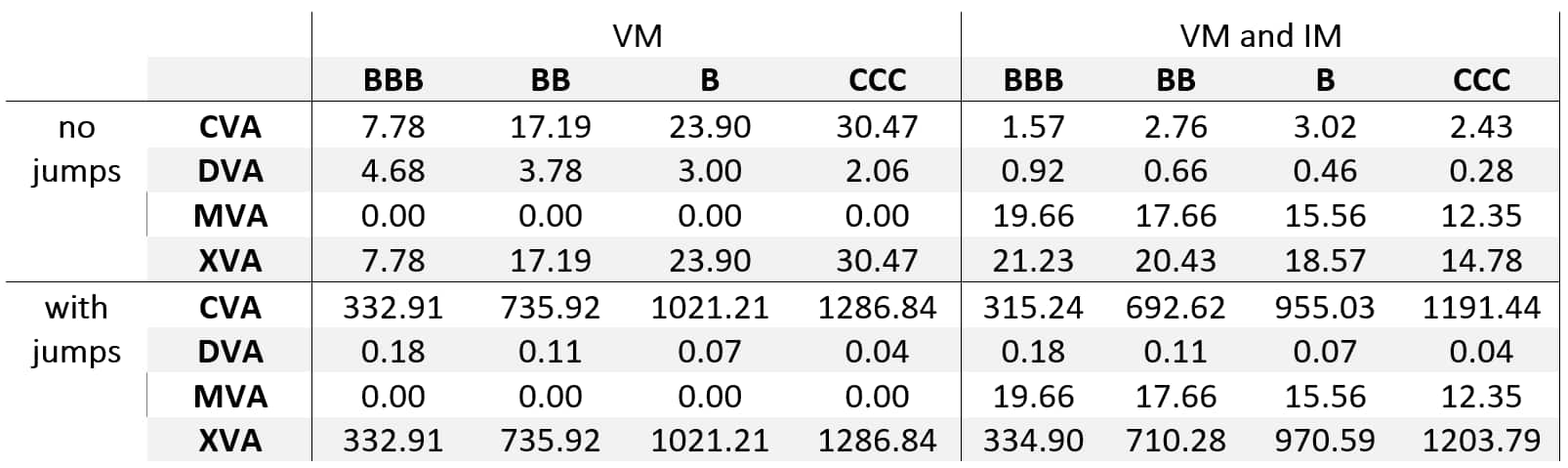

Table 1. Selected valuation adjustments for a partially (VM) and a fully (VM and IM) collateralized 10-year USD interest rate swap (pay fixed, receive float) for different counterparty ratings. Collateral consists of 10-year T-bonds only. All values are expressed in basis points of trade notional.

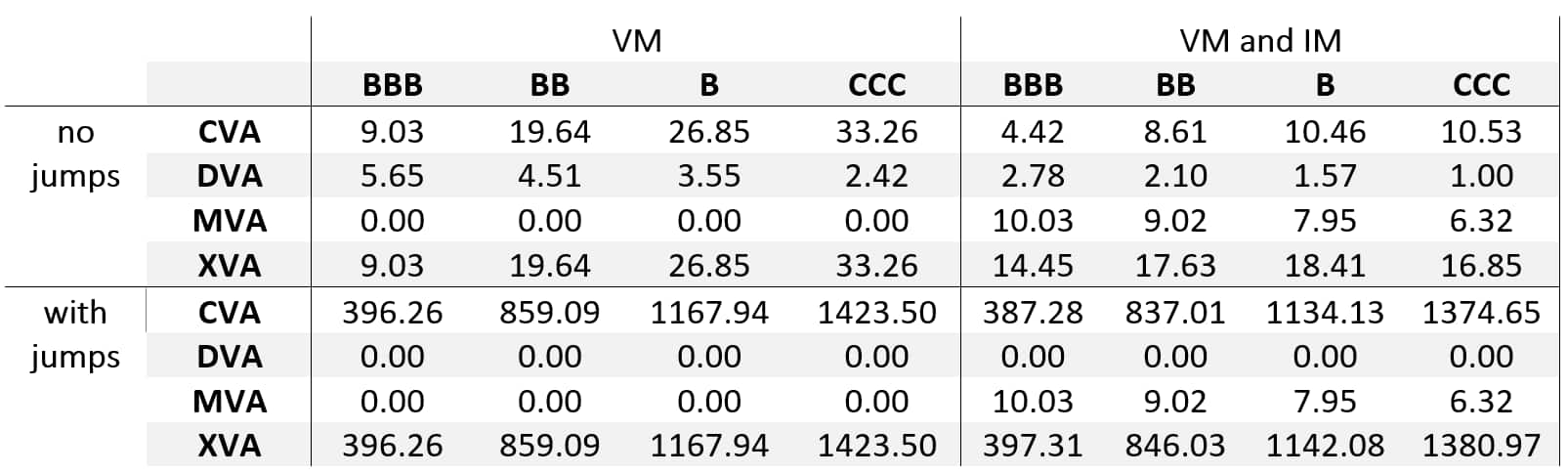

Table 2. Selected valuation adjustments for a partially (VM) and fully (VM and IM) collateralized resetting mark-to-market 10-year JPY/USD basis swap (pay JPY, receive USD) for different counterparty ratings. Collateral consists of JPY cash only. All values are expressed in basis points of trade notional.

Table 3. Selected valuation adjustments for a partially (VM) and fully (VM and IM) collateralized non-resetting 10-year JPY/USD basis swap (pay JPY, receive USD) for different counterparty ratings. Collateral consists of JPY cash only. All values are expressed in basis points of trade notional.

Two observations stand out. First, in the absence of jump-at-default, IM has the desired impact and substantially reduces the counterparty credit exposure. Not only are the CVAs smaller in the presence of IM for all counterparty credit ratings but the CVA reduction is also more material the lower the rating is. At the same time, the cost of IM (MVA) decreases with the counterparty credit rating, due to increasingly shorter effective lifetimes. As a result, an idle trade-off between CVA and MVA exists. That is, facing a higher rated counterparty, it would have been more cost-efficient, with respect to the XVA total, if the regulation had relaxed the IM rule for higher quality credit names. For instance, looking at the case of the interest rate swap (Table 1), XVA (expressed as a fraction of trade notional) increases from 3.22 bp to 20.45 bp for a BBB counterparty and decreases from 19.67 bp to 13.09 bp for a CCC counterparty when IM is exchanged in addition to VM. For all example portfolios, the crossover point lies somewhere between credit ratings BB and B.

Second, in the presence of wrong-way risk jumps, a similar behavior is observed, except that counterparty credit exposures and CVAs are now orders of magnitude larger. While IM and MVA amounts remain at the same level and the impact of IM on counterparty credit exposure is substantial in absolute terms, as above, its relative impact is meager. For example, the CVA for the interest rate swap (as the strongest of the three examples) reduces by at most 50% for all counterparties (e.g., from 51.18 bp to 28.02 bp for BBB), whereas in the absence of wrong-way risk jumps, CVA shrinks by multiples and nearly disappears when IM is included (e.g., from 3.22 bp to 0.01 bp for BBB). This is not too surprising, considering that as of the valuation date, just after trade inception, the IM amounts start out at 500 bp, 200 bp, and 450 bp of trade notional for the interest rate swap, the resetting cross-currency basis swap and the non-resetting cross-currency basis swap, respectively, and shrink (almost linearly) over the swaps' lifetimes. The jump-at-default wrong-way risk counterparty credit exposures without IM (VM only), however, are 1.8, 15, and 6.7 times larger [5], respectively, so the chance of full compensation is slim. The large multiples for the cross-currency basis swaps are partially attributable to the IM exemption carved out for fixed notional exchanges of cross-currency swaps and forwards, leaving out a portion of the exchange rate risk [1]. Finally, we note that the trade-off between CVA and MVA still exists, but the crossover point has moved further to the left to approximately BBB.[2]

These observations suggest that, in a severe wrong-way risk setting with jump-at-default, standard IM amounts are of limited use in mitigating counterparty credit risk. To shield against gap risk in this situation, it is paramount to identify and analyze such unique counterparty and portfolio combinations early and impose additional alleviating measures [7, 8].

[1] Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and Board of the International Organization of Securities Commissions (2020). Margin requirements for non-centrally cleared derivatives. Retrieved from https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d499.pdf

[2] Credit Suisse (2021). Special Committee of the Board of Directors Report on Archegos Capital Management [Report]. Retrieved from https://www.credit-suisse.com/about-us/en/reports-research/archegos-info-kit.html

[3] Gregory, J. (2015). The XVA Challenge: Counterparty Credit Risk, Funding, Collateral and Capital. John Wiley & Sons.

[4] Andersen, L., Duffie, D., & Song, Y. (2019). Funding Valuation Adjustments. The Journal of Finance, 74(1), 145-192.

[5] Puetter, C. M., & Renzitti, S. (2023). Jump-at-Default Exposure Modeling with Physical Collateral. SSRN Working Paper. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=4477691

[6] Chung, T.-K., & Gregory, J. (2019). CVA Wrong-way Risk: Calibration Using a Quanto CDS Basis. Risk, July, 1-6.

[7] Anfuso, F. (2023). Collateralized Exposure Modeling: Bridging the Gap Risk. Risk. February, 1-6.

[8] Arnsdorf, M. (2023). Leveraged Wrong-Way Risk. SSRN Working Paper. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=4340426

[1] As valued on 2022/07/29. We use the International Swaps and Derivatives Association's Standard Initial Margin Model (SIMM) to compute IM. Notional exemption rules apply for the IMs of the cross-currency basis swaps.

[2] We also mention another, higher order effect. When the default dynamics include a wrong-way risk jump component, IM has a greater chance of allaying counterparty credit exposure across many simulation paths. This is reflected in our results as well. For instance, again referring to Table 1 for the interest rate swap, exchanging IM in addition to VM reduces the CVA for a BB-rated counterparty by 8.04 bp (8.07 bp minus 0.03 bp) in the absence of jumps and by 57.18 bp (126.28 bp minus 69.10 bp) in the presence of jumps. Comparable findings apply for the other ratings and portfolio examples.

S&P Global provides industry-leading data, software and technology platforms and managed services to tackle some of the most difficult challenges in financial markets. We help our customers better understand complicated markets, reduce risk, operate more efficiently and comply with financial regulation.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

Location