Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — Nov 21, 2022

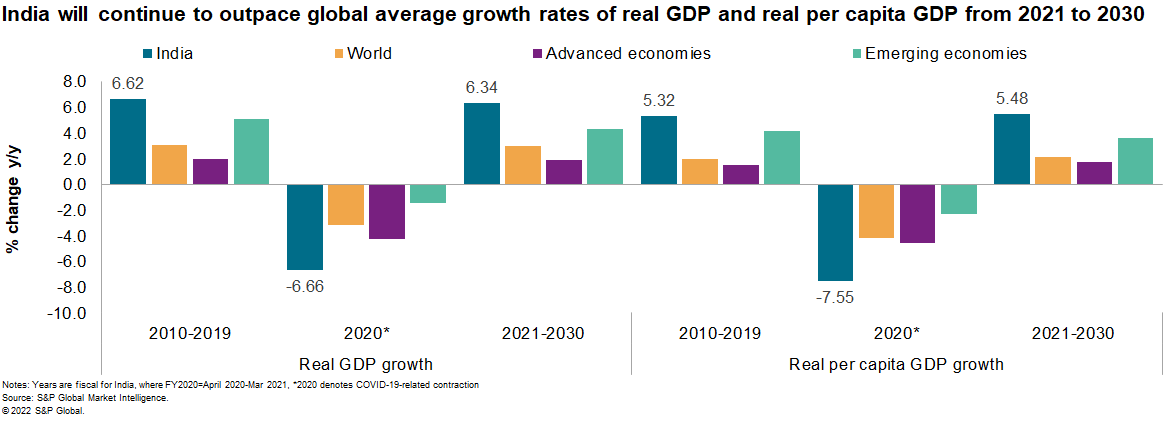

India's real GDP growth is projected to average 6.3% annually in FY 2021-30, enabling it to overtake Japan and Germany to become the world's third-largest economy (in nominal US dollar terms). Real income per capita is projected to achieve significant average growth of 5.3%, with Indian households becoming the greatest spenders among G20 economies.

These projections assume continued structural reforms, including trade and financial liberalization, infrastructure and human capital investment, and labor market reform. Progress is likely to be piecemeal: Although the current government has a parliamentary majority to pass legislation, trade unions are strong, comprise millions of members in sectors highlighted for liberalization, and have routinely opposed policies that they claim threaten job security and increase the influence of big business.

To circumvent stakeholder opposition, the thrust of economic policy will be to make India structurally more self-reliant. Doing so serves three goals: reducing import dependency, providing the labor force with suitable employment opportunities, and creating a more viable market for domestic and foreign investors.

Implementing Production Linked Incentive Schemes

The current government's main policy for boosting domestic manufacturing and facilitating large-scale job creation is through Production Linked Incentive Schemes (PLIS).

Introduced in 2020 and covering 13 sectors to date, under PLIS, the government offers incentives to domestic and foreign investors such as tax rebates, project-specific land acquisition, and license clearance, following a guaranteed increase in manufacturing investment, and subsequent achievement of output targets.

It is very likely that the government is banking on PLIS as a tool to make the Indian economy more export-driven and more inter-linked in global supply chains. India's manufacturing exports have struggled to gain global market share, while the share of manufacturing in India's GDP declined from 17% in FY 2009 to 14% in FY 2021.

A greater share in global value chains would also contribute to India's goals of improving leverage in multilateral negotiations and gaining advantage in its competition with mainland China.

Enabling 'national champions'

India's ambition to increase its economic power is unlikely to be limited to encouraging foreign investor participation. We are seeing, in effect, a promotion of 'national champions' - a handful of India-based conglomerates that the government is seeking to position as competitors to companies from mainland China, Europe, Japan, South Korea, and the United States.

The government is likely to actively advocate that foreign investors participate in joint ventures in India with these national champions. This is particularly likely in strategic sectors such as defense and semiconductors and in PLIS for renewable energy, electronics, and mining.

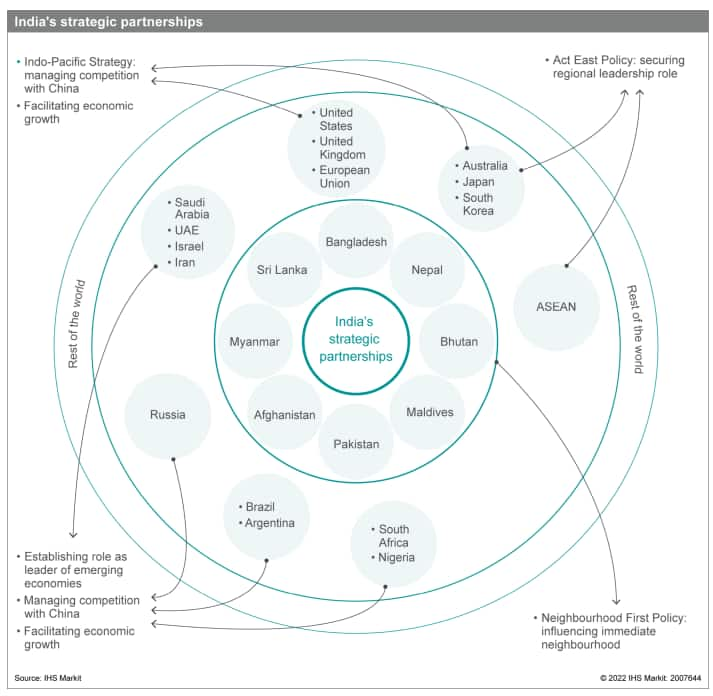

India's government also calculates that, as these conglomerates become more successful, they will be able to increase investment in neighborhood countries, in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and in emerging economies across the globe. Such investments would help India become a more integrated regional player and potentially increase its strategic leverage in emerging economies.

Deepening trade with political partners of strategic priority

S&P Global Market Intelligence Global Trade Analytics Suite (GTAS) forecasting data demonstrates India's increasing role in global trade: Between 2005 and 2021, the value of India's exports increased by 279.5% and imports increased by 301.6%. The US, the United Arab Emirates, and mainland China accounted for about 30% of India's trade in 2021 (in value), and India will pursue trade according to its concentric layers of strategic priority.

India maintains a trade surplus with the US and is accordingly pursuing trade negotiations to increase momentum in India--US trade. India consistently has a significant trade deficit with mainland China, and this is seen as a vulnerability. This dynamic encourages policymakers to seek alternatives, particularly in pharmaceuticals, automobiles, and electronics, where the aim is to make India a major exporter itself.

The overarching strategy is to closely link trade with political trust, focusing on future negotiations with:

Bilateral deals will be preferred over multilateral agreements like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which India exited in 2019. Successive Indian governments have alleged that multilateral agreements tend to increase its import dependence, with little focus on deepening ties in services. In bilateral arrangements, India can negotiate the use of non-US dollar currencies for trade, its position on export-import duties, access to critical minerals, immigration opportunities for its people, and compliance with labor and environmental standards.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.