Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Blog — 30 Mar, 2021

By Brenon Daly

Highlights

Blank-check firms spent more than $100bn on their 40 tech transactions through mid-March

Unlike VCs, SPAC investors can get back their money if they don't like the looks of the bet the blank-check firm plans to make with their money.

Introduction

Coming out of nowhere, a new player has disrupted the tech M&A landscape. Flush with billions of dollars and driven by the need to spend right away, special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) have created a third option for startups that, historically, have had to choose either to sell or go public when they want to exit.

And, as a record number of tech vendors have shown, this new hybrid alternative, which combines elements of both IPOs and M&A, can be much more immediate and far more lucrative than either option on its own. Through this wildly popular structure, startups can essentially sell themselves public. It's a kind of 'exit 2.0' for the tech industry, with SPACs opening a new route to quick riches in Silicon Valley.

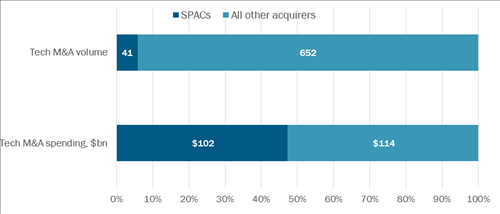

2021 Tech M&A Activity, by Buyer Type

Source: 451 Research's M&A KnowledgeBase. Data through 3/16/21.

To understand the disruption SPACs are causing – and are likely to continue to cause – it's revealing to contrast the current market power of these acquisition vehicles with their decidedly humble origins several decades ago. They weren't all born in boiler rooms, of course, but few of the blank-check firms in the early days could claim any true Wall Street lineage.

So how did these highly speculative transactions move from the fringes to the mainstream? What allowed them to shift from targeting penny-stock purchases to snapping up household tech names? How did the somewhat shady deals get legitimate?

Market: Unprecedented success for an unproven model

As with any market activity, the answer is always shaped by the interplay between supply and demand. We break down both sides of the equation in the rest of this special report. But before we get to the how of SPACs, far more important is the why around SPACs, since these speculative acquisition vehicles have upended the tech M&A market more than any other recent factor:

Demand: More SPACs than you can shake a stick at

Beginning with their underlying structure, SPACs are an unconventional – and largely unproven – option for all parties: sponsors, investors and targets. Compared with other financial products, SPACs come to market with a lot more open-ended questions. Cynically put, a largely unknown and untested blank-check firm raises money by selling shares in a company that does nothing, with the funds then used to open a back door onto Wall Street for a to-be-named-later company that may – or may not – be ready to be public.

Despite their checkered history, however, the current batch of tech-focused reverse mergers are far from the shadowy transactions of the past. (Investors, and indeed the SEC, may well recall some of the dodgy SPACs of the past, which might have involved, for instance, a deal for a vaguely operational and far-distant mining company that succeeded in only bilking a few widows and orphans out of their savings.) In fact, with actual GAAP metrics in SEC filings, the financials of target companies are more credible and rigorous than they likely kept as a private entity, where executives tend to 'round up' their numbers egregiously and talk about 'adjusted EBITDA' with a straight face.

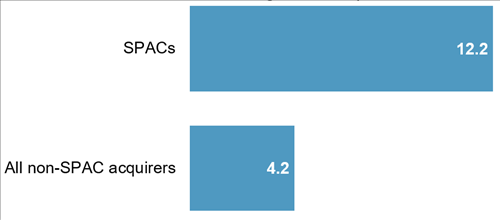

2021 Median Price/Sales Valuation, by Buyer Type

Source: 451 Research's M&A KnowledgeBase. Data through 3/16/21.

Still, blank checks require leaps of faith, both to finance and accept. To offset some of the unknowns, blank-check companies have filled in a few of the blanks. For instance, the current round of sponsors includes many well-known tech figures, rather than the B-listers that often pooled capital in other industries. (Michael Dell and LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman have both launched SPACs recently, along with dozens of executives and even private equity and VC firms that have worked in the tech industry for decades.)

Further, there are structural provisions that help de-risk blank-check investments, which can be thought of as VC-like bets on tech. (Whether typical retail investors are suited for the life on the sharp, unforgiving edge of the risk curve is another matter altogether. But based on their recent trading of GameStop shares, basement-based traders appear willing to roll the dice on pretty much anything.) Unlike VCs, however, SPAC investors can get back their money if they don't like the looks of the bet the blank-check firm plans to make with their money.

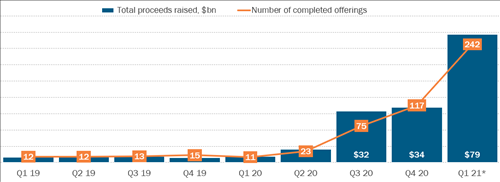

Recent Quarterly Offerings and Funds Raised by US-Listed SPACs

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence. Q1 2021 data through 3/16/21.

The blank-check formula is clearly working. More SPACs have raised more capital already in 2021 than any other year in history. Through mid-March, 243 blank-check companies had come public on US exchanges, netting $79bn in the record-setting spree, according to transaction screening data on S&P Global Market Intelligence. That slightly eclipses the full-year 2020 level, when the current SPAC craze was just taking off. For a more representative comparison, SPACs have already drawn in six times more money in 2021 than any of the prior four years.

Supply: Tech is a target-rich environment

Of course, not all of the SPACs' record haul of dollars is going to get spent on tech companies such as software vendors, electric vehicle makers and online businesses – all of which have been popular places for blank-check bets since mid-2020. But tech will get more than its fair share. A rough analysis of the language in the SPAC filings on the S&P Global Market Intelligence platform indicates that tech is likely to receive about one-third of the total dollars raised for acquisition.

Whatever the exact portion, tech is going to be overrepresented when it comes to SPAC activity, likely somewhere in the neighborhood of twice the 15% of the gross domestic product in the US accounted for by the tech industry. The outsized portion of tech-focused SPAC offerings also shows up when viewed against the broader equity capital markets (ECM). Depending on the year, the tech industry typically only matches (or even lags) the funds raised globally via conventional ECM offerings in other sectors such as healthcare and financial, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

And yet, tech has emerged as the single most popular market for SPACs to shop. Why? The simple answer is that's where the deals are likely to be found. As one indication, 451 Research's database of private tech companies lists about 150 tech startups that we estimate have topped $100m in revenue. This is by no means an exhaustive list. (To be clear, our database, which mirrors the enterprise focus of our overall research, includes only startups that have briefed 451 Research analysts who have then covered the vendor to some degree.)

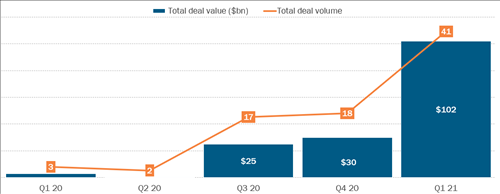

Recent Quarterly Tech Acquisitions by Blank-Check Companies

Source: 451 Research’s M&A KnowledgeBase. Q1 2021 data through 3/16/21.

Suffice to say, there are plenty of startups (a 'large cohort' in tech-speak) that have the scale to make their way to Wall Street, not to mention an enviable growth rate that will get investors excited for the aftermarket. Further, 'SPAC-quisitions' of these startups can be facilitated by their backers, since many tech companies have hit the natural expiration of their time in VC – and less often, PE – portfolios. (Investors, too, need exits so they can get back to their real job: raising their next fund.)

As an example of this capital market handoff, consider last month's reverse merger of 23andMe. Since its founding in 2006, the online genetics testing specialist had raised over $750m from more than 20 different investors, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. Already on the cap table was Virgin Group founder Richard Branson, who launched his SPAC (called VG Acquisition) last October and then parlayed that into the $4.4bn acquisition of 23andMe just four months after the raise.

23andMe is also representative of another trend that has come to define the recent SPAC spree in the tech industry: robust valuations. In fact, terms for the reverse merger value the online health site at 11.4x trailing sales, in line with the overall multiple for SPAC deals so far this year of 12.2x trailing sales, according to the M&A KnowledgeBase.

Even when pricing doesn't hit those lofty double-digit levels, reverse mergers can still be princely priced. For instance, the M&A KnowledgeBase shows that supply chain management vendor E2open fetched a 3.3x trailing sales multiple when it went private with Insight Partners in 2015. Last October, a SPAC set up by investment houses CC Capital and Neuberger Berman paid 8.4x trailing sales for E2open. That transaction closed last month.

Outlook: SPACs gotta spend

As dramatically as SPACs have already reshaped the tech M&A market, the real impact of this rapid – and accelerating – trend has yet to fully register. Blank-check companies are sitting on a mountain of capital, which they have only begun to spend down. And the clock is ticking on them. SPACs typically have about two years to spend the capital they raise, or they have to return the proceeds to investors. In other words, these acquisition vehicles have both the means and the will to transact in record amounts, even compared with other buyers they are going up against.

For the SPACs right now, the need to do deals – along with the competition for many of those deals – has never been higher. That comes through clearly when we again look at the severe imbalance between supply and demand in the current market.

Since January 2020, nearly 500 SPACs have successfully raised money to go after companies in all sectors, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. The platform adds 4-5 new offerings each day. Yet, on the other side of the ledger, our M&A database lists only about 80 reverse mergers for tech startups since the start of last year. As a reminder, our analysis of SPAC filings indicate that roughly one-third of all blank checks will be written for companies in the tech sector. That works out to tens of billions of dollars that's already banked, ready to be spent on deals by SPACs in the next year or two.