S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

BLOG — May 15, 2023

Following Croatia's accession on Jan. 1, 2023, seven out of 27 EU member states are yet to adopt the euro. While some, such as Bulgaria, would like to join but do not fulfill the convergence criteria, others, such as Hungary, Denmark and Sweden, lack the political willingness. Overall, we expect the current seven non-eurozone EU countries except Denmark and Sweden to join the currency union between 2026 and 2040, but it is political will rather than Maastricht criteria that will determine the timeline.

First comes Bulgaria

Bulgaria entered the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) II "waiting room" alongside Croatia in July 2020 but remains stuck, with its accession prospects hampered by global challenges and persistent political instability. In February 2023, Finance Minister Rositsa Velkova announced that the country would not meet the criteria to adopt the euro in January 2024, as planned. Instead, a new target date of 2025 was set, although analysts at S&P Global Market Intelligence think it won't be achieved until 2026 at the earliest.

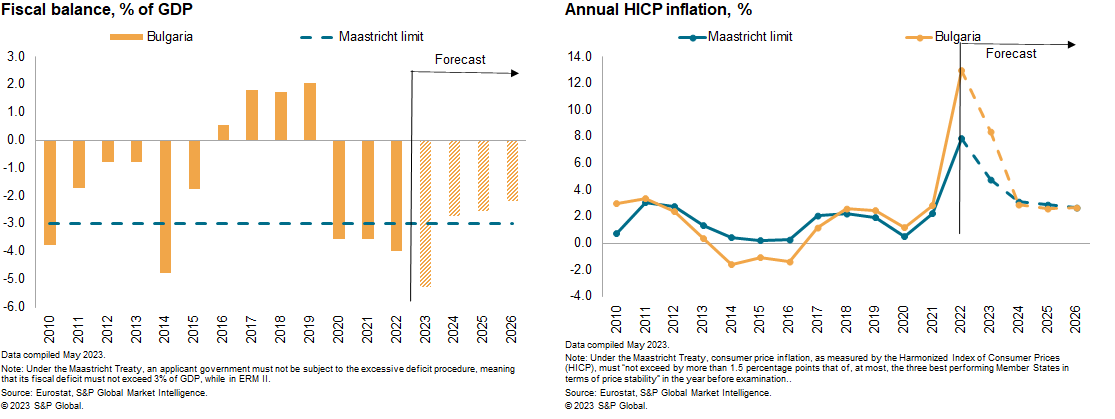

From an economic perspective, Bulgaria is yet to fulfil the criteria on price stability and fiscal discipline. Bulgarian consumer price inflation has exceeded the limit set in the Maastricht criteria since 2018. In our forecast, consumer price inflation in Bulgaria is projected to fall below the Maastricht limit in 2024. Even after accession is achieved, there are concerns regarding the sustainability of inflation convergence in Bulgaria over the longer term, especially considering the marked increase in labor costs over the past decade, which is expected to continue into the medium-term.

Following years of fiscal discipline, the global pandemic pushed the deficit close to 4% in 2020-21. However, with the whole of Europe facing similar challenges, the EU Commission suspended its excessive deficit procedure (EDP) rules for member states in 2020-22, and again until 2024 amid the fiscal pressures created by the Russia-Ukraine war. Continued fiscal discipline is needed to keep the budget deficit below the 3%-of-GDP target through the euro adoption timeline.

Bulgaria has gradually been implementing institutional reforms and legislative changes required for euro adoption, including improved financial supervision, central bank independence, the insolvency framework and strengthened anti-money laundering and anti-corruption legislation. However, the country must still adopt four outstanding draft amendments, which were committed to as part of the ERM II accession. The amendments concern personal insolvency, money laundering, insurance, and the legal integration of the Bulgarian Central Bank (BNB) into the Eurosystem. While this legislation has been prepared, the timeline for its adoption by parliament remains uncertain amid ongoing political instability following the April 2023 parliamentary election.

Further, several parties, including the Socialists and nationalists, are demanding a referendum on adopting the single currency, which is currently supported by only around one-third of Bulgaria's population (according to a survey conducted by Alpha Research commissioned by the government).

Then come the rest, maybe…

The tumultuous last few years, characterized by the need for large fiscal responses in the wake of the pandemic and a surge in inflation, have underscored the benefits of having an independent monetary policy and currency for most countries which are yet to adopt the euro. This complicates the strengthening of political and public support for eurozone accession.

After Bulgaria, Czechia is the most economically primed for eurozone accession. The industrial-heavy economy is closely aligned with the EU business cycle and is expected to meet all Maastricht criteria by the middle of this decade. However, it lacks political willingness to further the accession process anytime soon, with the current government refusing to set a target date.

Meanwhile, Romania has struggled to translate its hope into a political consensus for passing crucial reforms. The ones pertaining to fiscal discipline are key for sustainably narrowing the country's budget deficit to below the Maastricht threshold of 3% of GDP — a feat that is unlikely before 2026 at the earliest. Fostering institutional readiness will be another arduous process and is likely to take much longer.

While Poland and Hungary would also certainly benefit from some aspects of euro membership, eurozone membership will not be pursued as a serious political objective while the current Eurosceptic parties retain power.

There are limited advantages to joining the eurozone for the stable Nordic countries who have outperformed comparable export-oriented economies recently, and who already benefit from low borrowing costs. Denmark also already benefits from a stable currency through its peg to the euro, and Sweden's krona should stabilize once current market conditions stop overshadowing the country's endearing fundamentals, although the trend towards lower krona liquidity in forex markets might make a fixed peg against the euro a viable option. Recently, sentiment surveys amongst businesses have been flagging growing support for euro adoption in Sweden. The public is more reserved, making it politically contentious to revive the debate on euro adoption.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.