Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Research — 3 Mar, 2022

By Aline Soares

Introduction

Copper recycling will aid the transition toward a low-carbon global economy in the coming decades, with scrap as a key component of the circular economy. Currently on the rise as many copper-bearing products reach the end of their life, copper scrap supply boasts the potential to be a major disruptor to primary copper supply, and a force to satisfy the expected growth in copper demand from the renewable energy transition and electric vehicle revolution. In this article, S&P Global Market Intelligence assesses the key challenges faced by the copper recycling industry and forecasts copper scrap supply through to 2030.

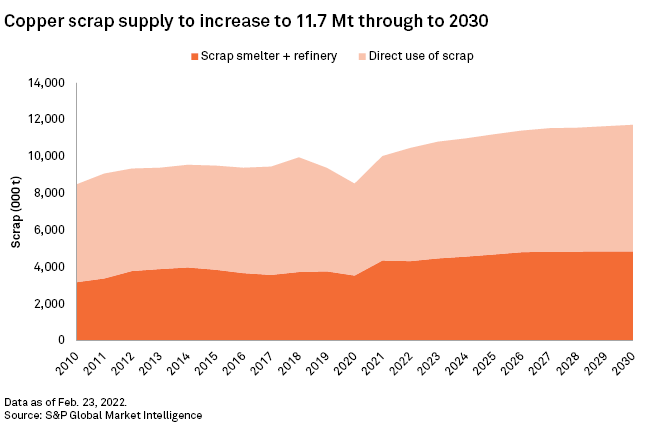

Increasing copper recycling from end-of-life products and process-generated scrap offers a sustainable pathway toward reducing global dependence on primary ore in a context of rising copper end-use demand. We forecast an increase in global copper scrap supply from smelter and refinery feed and directly melted scrap to 11.7 million tonnes in 2030. Despite the projected rise, the scrap recycling sector faces several challenges, some of which can be addressed by increased investment in capital equipment and technology, while an active role by governments will be crucial to the copper sector's impact on decarbonization. Moreover, new guidelines on the global trade of copper scrap could push domestic industries to invest in the copper secondary market while also creating new recycling hubs.

Increasing copper recycling from end-of-life products and process-generated scrap offers a sustainable pathway toward reducing global dependence on primary ore in a context of rising copper end-use demand. With desirable properties, mainly related to electrical conductivity, copper is used in multiple applications and sectors, and is one of the few materials that can be repeatedly recycled without a loss in performance. The scientific literature says that copper scrap consumption accounts for only 12.5% of the total environmental impact generated by the primary copper production process. Scrap is more energy-efficient and produces fewer greenhouse gas emissions in the smelting and refining steps.

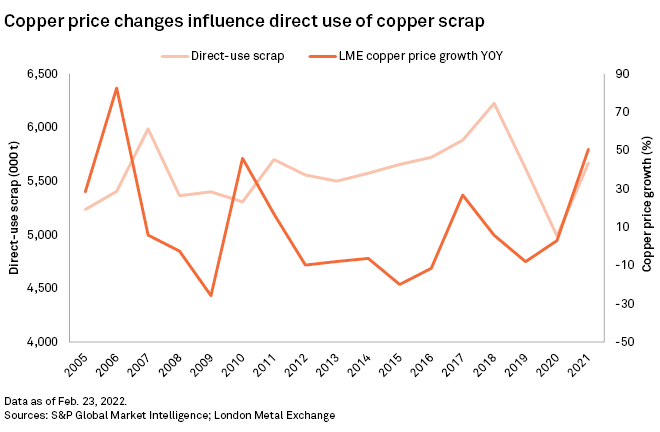

Decades of copper consumption have generated a "scrap fund," as the metal in a rising number of copper-containing products at their end of life has become available for recycling. The rate at which this copper material is recovered annually from the scrap fund is measured by the scrap recycling rate, which is typically higher in mature economies such as in the U.S., Japan and Europe. The copper scrap recycling rate is also influenced by the copper price; it tends to rise when the refined copper price goes up, providing an incentive for collection, and falls when the price goes down following reduced incentive.

We estimate the shares of scrap used as feed for smelters and refineries as a proportion of global refined copper supply averaged 9.0% and 7.5%, respectively, in 2010-20. We further estimate the amount of direct-use scrap, which can be melted and reused, to have recovered to 5.7 Mt in 2021 after falling to 5.0 Mt in 2020 from 5.3 Mt in 2010. Direct-use scrap's share of the global refined copper supply is estimated to have increased to 21.9% in 2021 from 20.5% in 2020 — still below 28.1% in 2010 following a wave of stricter guidelines on copper scrap imports by major market players such as China, Malaysia and Indonesia.

We forecast global copper scrap supply — comprising smelter and refinery feed and directly melted scrap — to rise to 11.7 Mt in 2030 from 10.0 Mt in 2021. Despite the projected increase, the scrap recycling sector faces several challenges that impact both the supply and demand sides of the market and will need to be addressed.

Scrap supply challenges

A key problem faced by the scrap industry is loss in the system, whereby scrap ends up in landfill sites. Scrap availability is also adversely affected by the long life cycle

Investment and technology boosts will be needed to lift the scrap recycling rates in developing nations. This involves more equipment for scrap processing and separation, trucks for scrap transportation and technological upscaling to deal with complex, diverse and fast-changing material compositions and product miniaturization.

China, the world's biggest copper consumer, has an estimated scrap recycling rate of around 50%-55%, according to academic studies. Even in Europe, where the copper scrap recovery rate is reportedly at around 60%-70%, there is room for improvement.

Investment in the scrap sector is growing, albeit from a low base, with China's Baosteel Resources Co. Ltd. investing in technology to extract copper scrap from used cars. In Europe and the U.S., copper-producer Aurubis AG has targeted investment toward three undertakings: increasing its recycling capacity, including electronic waste, or e-scrap; improving technology to convert complex materials into higher-grade scrap; and developing "closed loops" aimed at engaging its customers to end the cycle of metal waste. The United Nations estimates the e-scrap recycling market to exceed 74 Mt annually by 2030.

Copper scrap collection and processing is traditionally a low-margin business compared with mining and smelting, which is a disincentive to investment. Green policy incentives from governments will be required to facilitate more investment in the scrap sector, as well as broader supply chain innovation to enable circularity, including financial products, sustainable infrastructure loans, climate risk-related insurance and low-carbon performance rewards.

Scrap demand challenges

There are also constraints on the demand side of the scrap market. Technical limitations cap

While an important technological change is necessary to allow more scrap to be treated at smelters, new capacity additions — mostly from pure secondary smelters — will contribute to higher processing of copper scrap. E-scrap is used at specialist operations like Boliden AB (publ)'s Ronnskar smelter in Sweden, which has the technology to recover metals, including gold, from mobile phones and circuit boards. U.S.-based Prime Materials Recovery Inc. and Spain's Cunext Group launched a joint venture in February 2021 to build the first secondary copper recycling facility in the U.S. to produce copper anodes from copper scrap and copper fines. Furthermore, Aurubis will also start construction of a multimetal recycling smelter in Augusta, Ga., in August, with commissioning planned for 2024. The location of new recycling capacity should be strategically determined, with secondary smelters built close to where scrap is generated — urban areas, major cities and tech valleys — to minimize transport and reduce the carbon footprint of the process chain.

Scrap quality is also a factor influencing demand. Low-grade scrap is typically used in smelters. There are some specialist secondary smelters, but most of the scrap goes to primary smelters where it is charged with the concentrate. High-grade scrap is used in refineries, where it is cast into anodes and then refined. Most wire rod makers need a very-high-quality copper product, with 99% contained copper. Most of the scrap, however, has a lower contained copper content of 94%-96%, which trades at a discount and cannot be used by many wire rod producers. Direct-use scrap is the biggest demand component of copper scrap usage and is generally supplied by cut-offs from rod producers, including cuttings, borings, shavings and turnings.

Global copper scrap trade: environmental concerns set tone

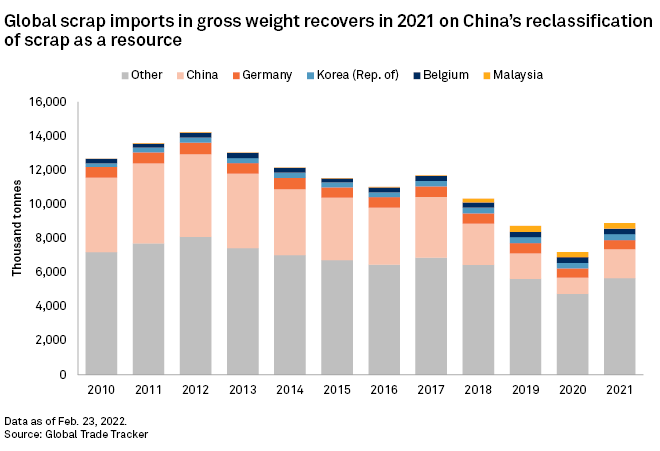

North America and Europe currently lack the technologies needed to utilize more of the generated scrap, such that most of their copper scrap is exported to China and Southeast Asia. With ample imports of mostly low-grade material, some countries have revisited their import guidelines, imposing higher standards on copper content and purity. These conditions are still in flux — further disrupted by new players like India or reconsiderations by Europe — with the potential to influence the trade flow of copper scrap, which has been mostly affected since 2018.

China has been the main importer of copper scrap, responsible for around half of the global imports in gross weight. Since 2018, the country has banned imports of lower-quality categories and restricted the flow of higher-quality grades via import quotas. Changes in China's import regulations were driven by an increasing concern with the environmental impact of processing low-grade scrap, which also generally contained higher impurities. The latest Chinese scrap import rule, established in 2020, has set the minimum copper content at 94%, and reclassified copper scrap as a resource, from waste material previously, and eliminated the quota system. This helped boost Chinese imports in 2021, with the gross weight of copper scrap entering China surging 79.5% year over year to 1.7 Mt.

In the short term, trade flows of recycled copper will be boosted by an expected improvement in logistic bottlenecks, combined with higher generation and collection of scrap triggered by the loosening of COVID-19 restrictions and high copper prices.

Since China readjusted its standards for copper scrap imports, Indonesia and Malaysia have emerged as major recycling hubs, reexporting a cleaner material to China. The two countries have recently been working toward new guidelines for metals scrap imports on concern over the processing of materials bearing copper and other elements. This can involve burning of plastic covers of electrical copper cables, which is harmful for the environment depending on the technology and infrastructure used by recycling units. In September 2021, the Malaysian government set a 0% impurity limit — one of the world's strictest — and a 94.75% minimum metal content threshold on imported copper waste and scrap, resulting in a ban on coated wire and cable scrap. Indonesia is more lenient, however, having settled on a 2% impurity threshold for its copper scrap imports in July 2021. The country revised its 0.5% impurity threshold proposal after concerted pushback from international recycling organizations such as the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries and the Bureau of International Recycling.

Copper scrap as commercial and environmental opportunity

India might capitalize on these stringent restrictions and allow imports of secondary material with lower metallic content. Details regarding its standards are currently under discussion. To attract more copper resources, the Indian government cut import duties on copper scrap by half in February 2021, to 2.5% from 5.0%, and is maintaining the new tariff for the 2022-23 fiscal year.

In November 2021, the European Commission revised its rules for shipments of waste materials, including copper and other metals scrap, proposing to restrict the export of hazardous material exports to non-European destinations with environmental standards lower than the EU's. The EU Commission also expects this realignment to reroute the flow of valuable secondary raw material within the bloc toward development of a more circular economy, with the added benefit of reducing energy use and carbon emissions as part of a decarbonization strategy.

Europe exported 2.3 Mt of copper scrap in gross content in 2021. Germany stands out as the EU's major copper scrap recycler, while outside the bloc, China is the largest importer, although European shipments to China fell more than half over 2018-21 compared with 2017, due to Chinese copper scrap import restrictions. The EU Commission is optimistic local industry players will be able to process the additional quantity of scrap, given their ongoing investment in recycling and recovery technology.

With a lack of infrastructure to promote circularity, the U.S. has been a major exporter of low-grade copper scrap, exporting approximately 919,000 tonnes of copper in gross weight in 2021. The U.S. currently does not have the capacity to treat low-grade scrap, although the country has taken steps to address this missing link in the copper supply chain, as it looks to reduce its carbon footprint and greenhouse gas emissions.

Key conclusions – We can't recycle our way to a fully decarbonized future

Future growth in the copper recycling industry boasts the potential to enable decarbonization, although scrap will need to be part of a much broader low-carbon energy transition drive. As discussed, the copper scrap sector faces many challenges, some of which can be addressed by increased investment in capital equipment and technology. An active role by governments will be crucial to the copper sector's impact on decarbonization, through promotion of green policies, incentives to accelerate investment and fostering conditions for wider circularity. Restrictions on global trade of copper scrap, triggered by new trade guidelines, could push domestic industries to invest in the copper secondary market while also creating new recycling hubs. In contrast with the steel industry, however, where a comparatively greater abundance of scrap supply could accelerate decarbonization, the constraints on copper scrap supply are expected to have a more muted impact, thus keeping primary copper ore as the major player in the copper market for the foreseeable future.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

Location

Segment