S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Research — Feb 13, 2025

By Francesca Price

On Dec. 3, 2024, China's Ministry of Commerce implemented export bans on key semiconductor materials, including gallium and germanium, to the US. While these minerals had already been subject to existing export restrictions introduced in July 2023, this is the first time China has specifically targeted the US. To date, US legislation has focused on strengthening the downstream part of the semiconductor supply chain, leaving US technologies vulnerable to upstream supply chain disruption.

US-China tensions centered on semiconductors and critical minerals are apt to continue rising as each government deploys the levers at its disposal, including restrictions on the upstream supply of materials key to the chip sector. Despite the Trump administration's opposition to many of the Biden administration's policies, measures targeting critical minerals supply chains, particularly onshoring efforts, will remain front and center. However, the extent and scope of changes to be rolled out in the coming months is still unknown.

Tensions rise as US, China seek technological superiority

By the end of December 2024, the Biden administration initiated a formal trade investigation into China's semiconductor industry, underscoring the ongoing trade and technology tensions, or so-called chip war, between the world's two largest economies.

The investigation will be conducted under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 and aims to identify unfair and unethical practices as levers to support revamping its own domestic industry. Days before the presidential transition in January 2025, Biden's administration also unveiled an export control regime that gives 20 close allies and partners uninhibited access to AI-related chips, while placing licensing requirements on most other countries. The policy aims to make it harder for China to use other countries to circumvent existing US restrictions to access chip technology. The execution and outcome of both provisions will be the responsibility of the new Trump administration.

Semiconductors are essential components of electronic devices, controlling the flow of electric currents in applications such as quantum computing, AI and other advanced technologies. They are highly material intensive and have a complex manufacturing process.

The US has made significant investments in recent years to build semiconductor manufacturing capacity, positioning itself as a global leader in fabless manufacturing. By avoiding the capital-intensive fabrication stage, fabless companies such as US-based NVIDIA Corp. and Advanced Micro Devices Inc. outsource semiconductor manufacturing to focus on design and innovation. Semiconductor manufacturing and assembly is now concentrated in Asia, with Taiwan, China and South Korea accounting for over 80% of the global supply of finished products. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. Ltd. is the largest manufacturer of advanced chips, with a greater than 50% market share of global production.

Despite the US' entrepreneurial function, the chip shortage during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed the country’s tenuous position in the semiconductor supply chain. The US has since passed a number of legislative responses to address this imbalance.

The Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors for America (CHIPS) and Science Act of 2022 is the largest US policy mechanism to expand investment in this field, promising $52 billion in grants, loans and other aid to onshore semiconductor research, development and production. In September 2023, the US Commerce Department issued a rule to prevent CHIPS funding from being used directly or indirectly to benefit foreign entities of concern (such as China).

Semiconductor raw materials supply chain remains concentrated

However, there is no provision in the CHIPS Act to incentivize the diversification of critical mineral supply chains for semiconductors, leaving the US — and most other Western countries — highly dependent on a handful of other nations for raw material supply. In addition to holding a monopoly over the manufacturing and assembly stages, China also has a majority share of the primary production (mining and/or refining) of several critical minerals that are essential components of semiconductors.

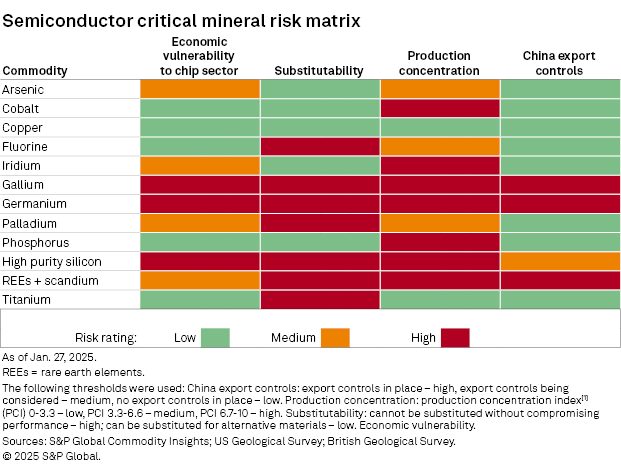

Arsenic, cobalt, copper, fluorine, iridium, gallium, germanium, palladium, phosphorus, scandium, other rare earth elements, high-purity silicon and titanium all contribute in varying quantities, across the many stages of the manufacturing process, to make a single chip.

Of these materials, gallium, germanium and silicon are considered the highest-risk minerals for the semiconductor industry. These three minerals are the most effective semiconductor materials and are used in the greatest quantities compared to others, such as arsenic, which are only used in trace amounts. Additionally, the primary driver for gallium, germanium and silicon is the chip industry, while demand for other named minerals is driven by other sectors, such as automotive, aerospace or construction. From a supply security perspective, the production of gallium, germanium and silicon are all highly geographically concentrated while also lacking suitable substitutes for this particular application.

While the CHIPS Act has succeeded in supporting new domestic chip manufacturing projects, the industry is mounting pressure on policymakers to address critical mineral supply chain vulnerabilities. China's move to implement an export ban of gallium and germanium to the US was a stark reminder of the risk of being dependent on any single country.

Just as the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 spurred investments in electric vehicle mineral supply chains, US semiconductor companies and industry groups are advocating for a set of tax incentives for mining, processing and refining projects, either domestically or in allied nations, aligned to semiconductor demand.

Despite President Trump's criticism of the Democrats' legislation, his approach to decoupling from China aligns broadly with the objectives of both the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS Act. In contrast to Biden's "friendshoring" approach to critical minerals, demonstrated by alliances such as the US-led Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), Trump is expected to follow an onshoring approach, with policy measures focused on building domestic mineral capacity. This would be welcome news for US chip companies such as Micron Technology Inc., Intel Corp. and Microchip Technology Inc., who have committed to major projects under the CHIPS Act.

In 2024, South Korea became the first member country to succeed the US in chairing the MSP, which — as the second leading producer of semiconductors globally — should bolster the connection between access to critical minerals and economic security for manufacturers. Canada, despite facing the prospect of new tariffs, is also keen to leverage its mineral resources and has proposed a deeper critical mineral alliance with the US to reduce dependency on China.

Entering his second term in office in January 2025, Trump is expected to take a relatively hawkish approach to China and has made his stance on tariffs clear. How he decides to handle the two actions focused on semiconductors introduced by former President Biden in the remaining days of his administration will provide an early indication of his approach and the extent to which he is likely to make semiconductors a focus in US-China relations.

[1] The production concentration indicator (PCI) characterizes the level of production concentration for each material at the mining stage and, where data is available, at the refining stage. Each share is multiplied by an ESG indicator to reflect the additional risk represented by countries with lower ESG standards. More information on the PCI can be found in the British Geological Survey's criticality methodology.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.