Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Language

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Podcast — 26 Oct, 2021

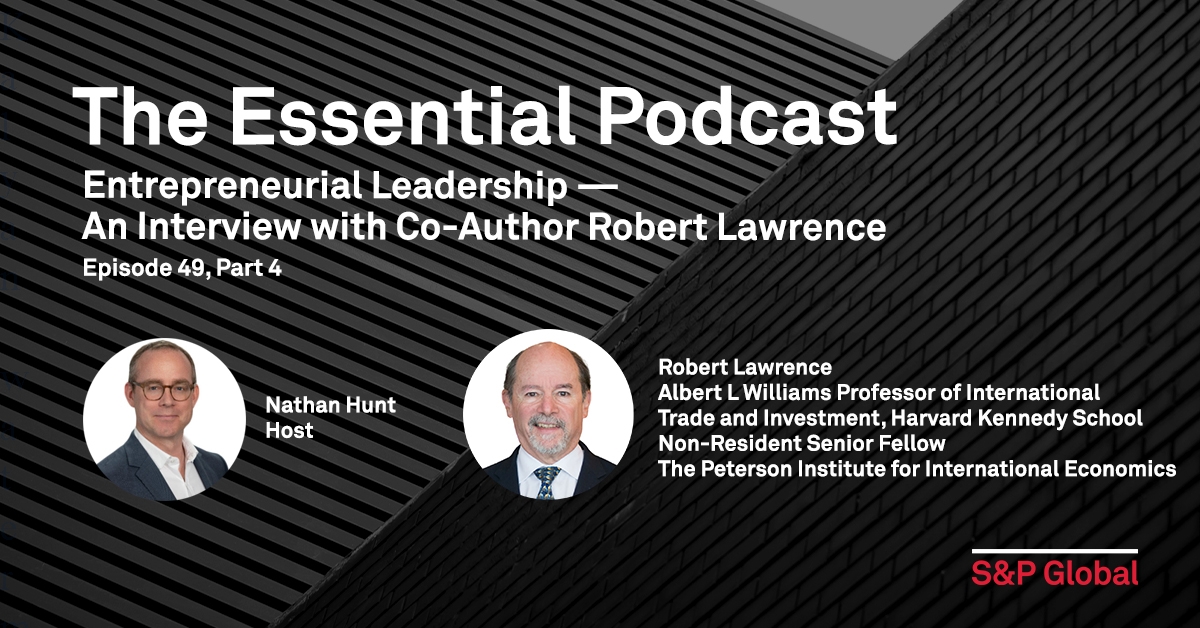

Robert Lawrence, Albert L Williams Professor of International Trade and Investment at Harvard Kennedy School and Non-Resident Senior Fellow at The Peterson Institute for International Economics, joins the Essential Podcast for Part 4 of a four-part series to talk about the report "Entrepreneurial Leadership Must Help Meet America's 21st Century Challenges in a Post-Pandemic World" and how his own work and career shaped his approach to the collaboration.

The Essential Podcast from S&P Global is dedicated to sharing essential intelligence with those working in and affected by financial markets. Host Nathan Hunt focuses on those issues of immediate importance to global financial markets—macroeconomic trends, the credit cycle, climate risk, ESG, global trade, and more—in interviews with subject matter experts from around the world.

Listen and subscribe to this podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and Deezer.

The Essential Podcast is edited and produced by Molly Mintz.