Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Language

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

S&P Global Platts — 22 Jul, 2020

By Paul Hickin

Highlights

While the coronavirus pandemic may have done permanent damage to oil consumption in the transport sector, strong growth in petrochemicals suggests peak oil demand could still be a couple of decades away.

Changing demand patterns also raise big questions as to how refineries and producers adapt in the post-pandemic world before demand falls from its eventual summit.

An accelerated shift to cleaner energy and electric vehicles, along with vehicle efficiency improvements, had already started to gnaw away at oil demand well before the coronavirus hit.

But what is striking is that those transportation sectors seen as more resistant to energy transition due to the challenges of them running on alternative fuels – airlines and shipping – have been hardest hit and will be the slowest to recover.

Some analysts see global oil demand now peaking later this decade, while others believe it may never return to the giddy heights of 100 million b/d.

Further out, the most likely case according to S&P Global Platts Analytics’ Scenario Planning Service is 3 million b/d removed from oil demand to 2040, with aviation the most impacted sector. But that also needs to be put into context.

Jet and marine fuels make up a relatively small piece of the crude cake, at about 8% and 6%, respectively. The petrochemicals sector, which includes materials used more regularly in a coronavirus world, from mobile phones to packaging and hand sanitizers, has been quietly carving out a bigger share at around 19% of overall oil demand.

Platts Analytics sees continued growth in long-term petrochemicals demand as potentially delaying peak oil demand to 2041. Indeed, many plastics have sustained net positive growth even during the downturn over the past few months.

The International Energy Agency is also skeptical of those writing the obituary for oil demand growth.

“If oil demand goes back to 100 million b/d I would not be surprised,” said Executive Director Fatih Birol, said in early July. “And under a strong recovery, I would not be surprised if it went higher than that.”

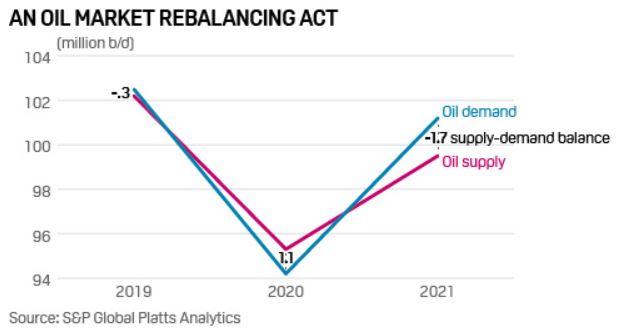

Platts Analytics sees oil demand down at 94.2 million b/d in 2020 before potentially reaching a high of over 100 million b/d in 2021, should the world make a fast and sustained recovery.

Peak oil will also be impacted by assumptions around the long-term price of oil and its alternatives. Petrochemicals growth, and namely plastics, for example, will largely be affected by recycling economics. Then there is the replacement of traditional oil-powered road transport by electric vehicles.

Anyone looking at the demise of crude should look at the case of coal, which remains embedded in the economies of China and India, with over half of the world’s more than 10,000 coal power plants located in the two countries.

Global seaborne trade in coal, both thermal for use in power plants and coking used for steel-making, remains strong. Both countries have made commitments to being low carbon economies but it will still take time.

At the other end of the wedge, assumptions that oil peaks in a couple of decades’ time masks the fact that demand growth may be anemic, at least compared with historic annual growth trends of above 1 million b/d.

The potential impact of coronavirus on oil demand is varied and contradictory. For every claim that social distancing will hamper air travel, reduce commuting and physical shopping, there is the counter-claim that people will switch from public transport to cars and electric vehicles take-up will stall due to low oil prices.

“Some say demand for oil is falling because we are changing our lifestyles, I’m not so sure,” Birol said. “Teleworking alone is not going to send oil demand lower. We will need the right policies.”

Brian Gilvary, the former CFO of BP, noted that investor returns will be “crucially important” still in any energy transition.

“One of the things I’ve heard from some investors is they are not looking for energy companies to dilute returns by investing in renewables,” he told Platts in an interview July 9.

Go deeper: Podcast – BP’s former CFO Gilvary on how to survive $40/b crude

The IEA and IMF have called for $1 trillion in spending to revitalize economies and boost employment while making energy systems cleaner and more resilient under a pandemic recovery plan. But whether governments can deliver on a greener future by investing in the necessary infrastructure post-coronavirus remains open to debate.

And technological progress is still needed to lower the costs and boost the availability of EVs, solar and wind power, and other alternative energies.

So oil’s future, the transition to cleaner energy and demand for oil-derived products are not just in the hands of us as consumers and workers, but also rest with policy makers and tech gurus.

Can EVs shift from being a niche product to a mass-market good? Can cleaner fuels such as green hydrogen offer a solution in road use and beyond?

Only one thing is certain about energy use beyond coronavirus: The traditional models for understanding energy transition are broken and will need to be rebuilt as oil demand returns.

Content Type

Segment

Language