Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Language

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

Events

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

Events

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

S&P Global Platts — 5 Aug, 2020

By Tim Bradner

Dwindling prospects, in its view at least, changes in corporate strategy, the failure to commercialize large stranded gas reserves and Alaska’s volatile politics and frequent changes in taxes all appear to have played a role in the company’s decision to sell its legacy North Slope holdings.

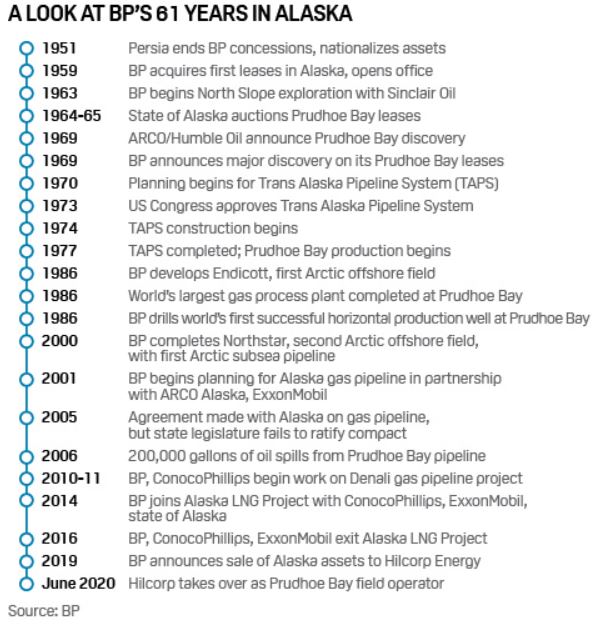

BP left a long legacy in Alaska, spearheading the exploration in the early 1960s that ultimately led to the discovery of Prudhoe Bay, North America’s largest oilfield.

As a Prudhoe Bay operator, BP became known for technology innovations, including drilling the first commercially successful horizontal production wells. That innovation set the stage for US shale oil and gas development using a combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing.

BP sold its Alaska holdings July 1 to Hilcorp Energy, a midsize Texas-based independent that owns and operates smaller Alaskan fields. Hilcorp has a reputation for purchasing mature, declining assets and aggressively redeveloping them.

Hilcorp also acquired BP’s 50% share of Milne Point, another producing field on the slope, and Liberty, an undeveloped offshore deposit.

The story of major companies like BP discovering and developing large finds and then selling them to lower-cost operators is an old one played out many times, even by BP in the North Sea, but the company’s Alaska story is also a tale of geopolitics and corporate strategy played on an international scale.

It started when BP was kicked out of prized holdings in Persia by a populist government in the 1950s. Denied access to its key crude oil source for European markets, BP felt survival depended on diversification into US markets.

At the time there were US controls on imported oil, so BP had to not only find a US marketing partner but also a domestic source of crude oil. US companies controlled existing domestic production in states like Texas, but BP’s geologists felt the remote Alaskan North Slope offered opportunities for big discoveries with potential to give the company an entry into the US.

In 1963, BP began drilling the first of a long string of dry holes on the slope, which finally led to the prize at Prudhoe Bay in 1968.

Atlantic Richfield (ARCO) and Humble Oil, now ExxonMobil, in a joint venture followed BP in exploring on the North Slope and actually drilled the first discovery well, but BP quickly drilled on its Prudhoe Bay leases and wound up with most of Prudhoe’s 9.6 billion barrels of oil. ARCO and Humble wound up with most of the large gas resource in the field.

But while BP now had a large source of US crude it still needed a marketing arm, which led it to acquire Standard Oil Co. of Ohio, or Sohio, an experienced US Midwest marketer. This allowed BP’s diversification out of Europe and ended near-total dependence on Middle East oil.

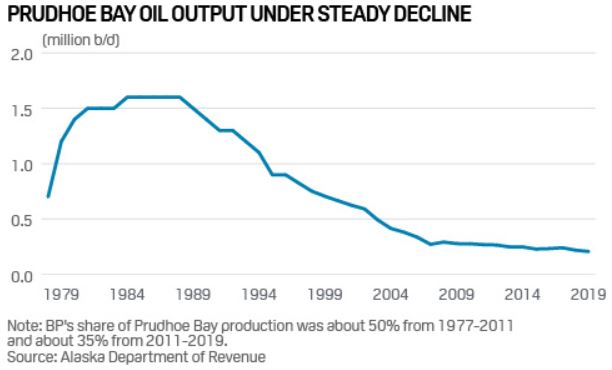

But things changed for BP in Alaska as years passed. The big Prudhoe field began its decline in 1988 and now produces about a fifth of what it did when output started.

Hopes for finding more Alaska super-giants soon faded. ARCO, with BP as partner, developed the nearby Kuparuk River field, then, and still, the second-largest North America producer, but other discoveries proved to be midsized.

The super-giant prospects BP was looking for weren’t there.

Go deeper: Podcast – BP’s former CFO on surviving $40/b crude

The company was keen on the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge east of Prudhoe, where the geology offered prospects for really big finds. BP teamed up with Chevron to drill an exploration well. The results of that are still confidential, but prospects for developing any find in ANWR dimmed as US conservation groups lobbied Congress to keep the area closed.

Congress did finally approve leasing and exploration in the refuge last year, but the refuge is seen as so politically radioactive that interest by BP and other major companies seems to have cooled.

Still looking for ways to grow its Alaska business, BP focused on the huge gas resource in the Prudhoe reservoir and teamed up with other companies and the state of Alaska with plans for a $40 billion-plus natural gas pipeline.

BP felt if Prudhoe gas could be marketed, it would help pay field costs and increase profitability for continued oil production.

An all-land pipeline through Canada was planned but later scuttled when the shale gas revolution sent US natural gas prices plummeting. An alternative plan to export the gas as LNG form south Alaska is now at an advanced stage and a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission license was issued earlier this year, but prospects in the target Asia LNG market seem grim.

Thwarted on several fronts, the final straw for BP may have been a steady cycle of state tax increases on oil. A citizen initiative that would double taxes on Prudhoe Bay will appear on the general election ballot in November. Last spring, BP officials acknowledged the threat of new taxes was a significant factor in the company’s decision to sell.

It had become clear to BP that operating a declining and increasingly marginal asset, with costs rising, no longer fit its long-term strategy. The higher overhead of a large company and multiple layers of making decisions no longer worked well for Prudhoe Bay. Companies like Hilcorp that are smaller and quicker with decisions are better at exploiting opportunities for new oil at Prudhoe.

Alaska has been good for BP, basically enabling its growth out of Europe and the Middle East. Now BP is reinventing itself for a new, less carbon-intensive world, and in that plan, Alaska had become a distraction.

Content Type

Theme

Location

Segment

Language