S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

By Sylvain Broyer and David Henry Doyle

Highlights

The CMU has the potential to turn the tide in Europe. At present, its substantial savings are ineffectively allocated in a fragmented financial sector dominated by banks. As a result, investment, innovation, and growth are subdued.

Asset managers and financial market infrastructure companies are set to be major beneficiaries of the CMU. However, European banks can also benefit from more developed capital markets in the EU. At the retail level, a deeper equity culture could yield bigger returns for both savers and investors.

Growing momentum behind sustainable finance can help unlock the CMU’s potential, while lower-for-longer interest rates risk reinforcing the reliance of the EU economy on debt.

For a PDF of this report, please download.(opens in a new tab)

This article collects thought leadership pieces from three S&P Global divisions on the EU Capital Markets Union 2.0 project. We feature contributions from S&P Global Ratings (the sections on Lower For Longer Interest Rates and Bank Consolidation by the Ratings Research and Financial Institutions practices), S&P Global Market Intelligence (CMUs, Sustainable Finance and SMEs) and S&P Dow Jones Indices (A Deeper Equity Culture). Though the contributions reflect each division’s own separate perspectives and requirements, together they reflect S&P Global’s current thinking on this important project.

Part 1

The view from S&P Global Ratings Research

The economic benefits of integrating EU capital markets are obvious but policy steps toward doing so have so far aimed at the low-hanging fruit. Yet, the current environment of slow but steady growth and loose financing conditions allowed by low-interest rates is unlikely to address the twin issues of inadequate equity financing and capital mobility in the European economy.

We expect interest rates in Europe to remain as low as they have been for an extended period. Therefore, the preference of European corporates for loan and debt financing instead of equity financing is likely to continue unless the CMU becomes reality. Indeed, the consolidated debt of EU-27 nonfinancial corporates reached €10.3 trillion by the end of 2018, with most European companies still obtaining their financing from local banks (see chart 2). With such low interest rates, the euro is on the verge of becoming a funding currency like the Swiss franc or the Japanese yen. For instance, French corporates are currently borrowing euros at very low interest rates to invest in high-yielding foreign markets (see “What's Behind The Rise Of French Corporate Debt?,” S&P Global Ratings, published on March 13, 2019). Consequently, the longer interest rates in euros remain low, the more the European economy will probably rely on debt.

A diversified funding structure for the European economy does not only enhance financial stability, it also encourages investment. According to the European Investment Bank, the lack of finance for equity growth is among the biggest reasons for the dearth of big new innovators in the EU, especially in the digital and technological sectors. Venture capital, which startups need to expand quickly, is clearly underdeveloped in Europe (see chart 3) compared with other forms of financing. One risk of a longer period of low interest rates is that capital might continue to flow toward sectors with low productivity. This would lead to the overexpansion of the construction sector to the detriment of other sectors, as well as to loan "ever-greening" to weak borrowers and the "zombification" of the economic fabric with inefficient actors, as a study by the Bank for International Settlements argues. Lower-for-longer interest rates might also increase market concentration and reduce productivity, according to an ECB paper. The CMU would, in our opinion, counteract these risks with incentives to increase equity financing and venture capital.

Recent developments in the allocation of European savings make the case for the CMU even more compelling in a context of low interest rates. Institutional investors in search of yield are increasingly investing in assets outside of the EU. European money market funds have widened their exposure to U.S. dollar repurchase agreements (repos) to benefit from a pickup in yields over euro repos (see chart 4). Our data also suggest that some European insurance companies are increasingly shifting their asset portfolio toward U.S. dollar-denominated assets. What's more, very low interest rates are pushing households to save a higher share of income (see chart 5), when neither economic conditions nor inflation expectations would typically account for such behavior. A key reason might be an insufficient return on savings. Europe has taken steps in the right direction, with the European Parliament giving the green light in April last year to regulation for pan-European personal pension products (PEPPs), but this does not close the gap between an ample pool of domestic savings and huge needs for domestic investment.

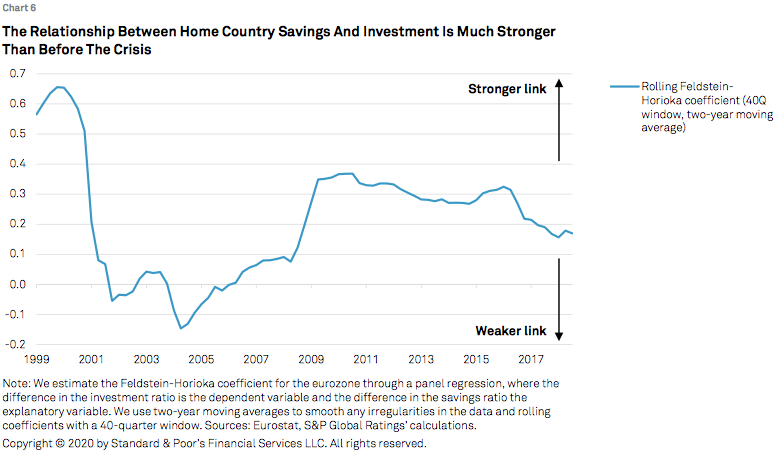

Finally, European financial integration has yet to recover to its pre-crisis level. Since 2009, Europeans have been less inclined to pool their resources to lend to each other. We find that, while the link between home country savings and investment disappeared in the early 2000s, it reappeared and has remained more or less stable since the financial crisis (see chart 6). Other indicators of financial integration from the ECB paint the same picture (see chart 7). Some progress has been made in terms of the pricing of European financial assets, with interest rates converging among eurozone countries thanks to the ECB's set of measures, but not in terms of cross-border financing. The home bias remains strong among noncore banks and insurance companies. Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese banks are as much exposed to domestic sovereign risk as in 2012 (see chart 8), while domestic government bonds still comprise more than 60% of holdings in government bond portfolios of French, Italian, and Spanish insurance companies, according to the "EIOPA Financial Stability Report 2018."

Box 1

We believe that reliance on bank loans and debt is one key reason the global financial crisis hit the eurozone harder and longer than the U.S. or U.K. Increasing the equity of European corporates could help lessen the vulnerability of their external financing to sudden stops in credit markets when the cycle turns. Increased equity could also help contain a further rise in debt or leverage by promoting firms' ability to invest. The fragmentation of European financial markets has increased since the financial crisis on the back of higher risk aversion, tighter banking regulation, and the eed to wind down nonperforming loans. The result has been less capital mobility within the eurozone, especially less capital flowing from core countries to noncore countries, which prevents the European economic and monetary union (EMU) from reaping all of the benefits of the single currency.

Following the relative success of the Banking Union, the EU embarked on two major financial projects: the CMU (2015) and the Action Plan On Sustainable Finance (2018). The CMU aims to build deeper, more liquid, homegrown capital markets, while the Action Plan seeks to reorient investment to engineer and facilitate the transition to a more sustainable, low-carbon economy. Initially launched by the Juncker Commission, the CMU aims to:

The CMU is designed to complement the Banking Union by reducing reliance on bank funding and allowing for more shock absorption through markets in times of crisis. It is also seen as part of the drive to complete the EMU. It may serve as a second leg to a future financial union, one of the four pillars of the post-crisis framework for the EMU.

The long-term stated objectives of EU policy are to break the sovereign-bank nexus, foster private (versus solely public) risk sharing, and create a more resilient and efficient financial sector. The CMU's first four years focused on a broad set of measures to facilitate external financing toward equity, reduce the cost of raising capital, to streamline securitization, and reduce investors' home bias.

Part 2

The view from S&P Global Ratings’ Financial Institutions Practice

Many of Europe's banking groups have a longstanding profitability issue, and their subdued earnings prospects weigh on S&P Global Ratings' view of the sector. See"European Banks Count The Cost Of Inefficiency," S&P Global Ratings, published on Oct. 22, 2019. At first glance, a full-fledged CMU might be an additional factor that could undermine their business model. On balance, however, we think the CMU might offer opportunities to banks.

The CMU could help boost European asset managers and financial market infrastructure companies (FMIs; for example, exchanges, clearinghouses, and central securities depositories). As more capital flows to the capital markets from banks’ balance sheets, the position of FMIs as facilitators of economic growth and investment would become more important. While FMIs would continue to derive most of their capital market revenues from activity in the most liquid, blue-chip securities, the CMU could help increase the number of listed securities and provide a structural boost to trading, clearing, settlement, and depository volumes. Asset managers, like banks with asset management capabilities, could see more demand from savers. However, for this to happen, debt and equity in smaller companies needs to be attractive and investable – a tricky balance to achieve in practice. We believe that concentration limits and liquidity concerns would hinder investment by the large, institutional funds that today form the bulk of European pension savings. Smaller, retail-focused funds may need some fiscal incentives to encourage investors to switch from deposits and would need to be careful to avoid the liquidity problems seen in recent months. Finally, exchanges would likely need to foster liquidity in these securities, for example, through development of investment research coverage and market making.

We think there are four ways banks would stand to benefit from the CMU:

(opens in a new tab)

(opens in a new tab)The CMU is not only relevant to European players. It would likely lower barriers to entry into European savings and investment markets for rivals from non-EU markets. In particular, large U.S. banks could take market share from European banks by weighing in with their expertise and global networks in investment banking and wealth management (see chart 10). Worsening the situation is that many European banks have exited from major cash equities markets, with all but the biggest global banks struggling to generate decent returns.

Increasing competition in Europe, including from non-EU banks, has the potential for making large European banks align with other major foreign investment banks. We assume the structure of the European banking sector would more resemble that of the U.S. over time if the European capital markets were to look more like the U.S. capital market. This would, in our view, likely entail consolidation among European banks. However, cross-border consolidation would probably require the EU to complete the Banking Union in parallel with creating a CMU.

Part 3

The view from S&P Global and S&P Global Market Intelligence

Rapidly increasing EU retail demand for sustainable investment matches EU citizen concerns

EU citizens now reportedly consider climate change as the second most important challenge at the EU level after a strong increase (up 11% since 2018), according to Eurobarometer surveys (see chart 12 and chart 13). The environment, climate, and energy now rank third at national levels (up 10% since 2018).

The EU's goal of carbon neutrality by 2050 has captured the imagination of its citizens – it remains to be seen whether it will capture investors’ imagination. Every two years, the European Sustainable Investment Forum (Eurosif) takes stock of growth in retail interest in socially responsible investment (SRI) assets, by surveying trends in institutional and retail ownership. Since 2013, retail socially responsible investing has grown from a base of just 3.4% (with the remaining 96.6% held by institutional investors), to 22% in 2015, and 30.77% at last count in 2017 (see chart 11).

EU citizens now reportedly consider climate change as the second most important challenge at the EU level after a strong increase (up 11% since 2018), according to Eurobarometer surveys (see chart 12 and chart 13). The environment, climate, and energy now rank third at national levels (up 10% since 2018).

Although Europeans are good savers, they tend not to invest in equities or equity-like products. The Association for Financial Markets in Europe has shown that the average EU household accumulates savings at a higher rate than elsewhere around the world. The EU net savings rate of 6.1% compares with 3.3% in the U.S. and 2.6% in Japan. However, Europeans tend to hold 32% of those savings in conservative instruments like cash and deposits. U.S. households allocate only 13% to cash and deposits according to our estimate.

The think tank New Financial estimates that if households in the EU-27 reduce their preference for bank deposits to the same level as in the U.K., it could free up nearly €2 trillion for investment in the economy. If households were to increase the share of mutual funds in their financial savings (7.9%) to the level of U.S. households (11.6%), we estimate that would release €1.2 trillion in potential investment. This sum is a multiple of the European Commission’s €260 billion annual additional investment needed to meet EU Green Deal targets.

Though at this point speculative, were investors offered financial products in line with their climate and environmental concerns, Europeans may be inclined to invest (see "EU Green Deal: Greener Growth Doesn’t Necessarily Mean Lower Growth," S&P Global Ratings, published on Feb. 10, 2020).

A recent 2019 study by the University of Cambridge demonstrated that public interest in sustainability influences investment preferences when suitable information is provided. The research examined the decision-making behavior of a sample of 2,096 U.S. citizens when presented information about a fund's sustainability impact alongside standard financial data. Participants were given a choice between two funds, one showing higher sustainability features and the other showing equal or superior past annual returns of up to 3 percentage points.

Significantly, the research found that the median saver preferred a sustainable fund even if it meant sacrificing up to 2.5 percentage points of annual returns. This result suggests that savers currently value sustainability, and that suitable information on the ESG impact of funds can influence the public's investment decisions. Moreover, the study found that participants younger than 35 years old and inexperienced savers, key target CMU demographics, had a particularly strong preference for sustainable investment.

The Cambridge research suggests that educating EU savers about the consequences of their current investment choices, specifically the low yields offered by deposits, combined with the sustainability impact of their options, has the potential to raise the low participation rates of retail EU investors. What remains to be seen is whether investors will, if given the opportunity, part with their money.

At the wholesale level, the EU's Action Plan On Sustainable Finance could, if successful, also attract international capital seeking sustainable investment opportunities. The world's first capital market to provide a regulated environment for sustainable assets could help minimize the practice of greenwashing, maximize liquidity for global sustainable capital, as well as allow new green asset classes, products, and tools to achieve scale more quickly.

The EU has the potential to create a capital market that differentiates itself by integrating ESG standards and embedding environmental choices at a product level (see “Credit FAQ: The EU Green Taxonomy: What’s in a Name?," S&P Global Ratings, published on Sept. 11, 2019). While this overlay of ESG data could attract new retail investors from within the EU--in line with the analysis above--it could also attract new sources of international capital seeking greener opportunities. International issuers could be tempted to raise finance through the new EU standards to prove their credentials.

Indeed, the success of the EU's UCITS fund wrapper--a series of EU directives dating to 1985 that establishes a uniform regulatory regime for the creation, management, and marketing of collective investment vehicles--suggests that European regulation can provide added security and investor protection that appeal to international markets. Net assets in UCITS domiciled in the EU were €8.7 trillion at year-end 2018, according to the Investment Company Institute (see chart 14). The potential for one or more EU regulated standards or vehicles in the area of sustainable finance to reach this scale is not inconceivable.

However, the challenge of establishing ESG norms and standards – which is already well under way through the EU's Green Taxonomy proposal – would be facilitated by developing markets to meet investor needs. While a Green Bond standard may serve as a useful label to provide investors with assurance about the nature of their holdings, ensuring that wholesale markets and distribution channels exist to offer and trade such instruments on a competitive basis, requires more than product regulation, disclosure rules, and labels.

In fact, it could be argued that Europe might be losing its edge. According to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, the U.S. closed the gap with Europe for sustainable investment assets between 2016 and 2018. Indeed, the latest study found that Europe's share of the overall market declined to 49% from 53% of total professionally managed assets. Moreover, while from 2014 to 2016 European sustainable assets grew at an annual rate of 12%, this declined to 11% from 2016 to 2018. The compound annual growth rate from 2014 to 2018 was just 6% in Europe compared with 16% in the U.S. and 308% in Japan (see table 1).

A complex ecosystem is required to make any capital market a success. However, the genuine domestic and foreign interest that exists in finding sustainable investment solutions could be a real catalyst for the EU to boost retail participation rates and to distinguish the CMU from rival international capital markets. New momentum from sustainable finance by European retail and international institutional investors could give a genuinely distinct edge to the CMU.

More importantly, deep, liquid, and integrated capital markets will be necessary if the EU is to meet its ambitious climate transition and carbon neutrality goals. By closely coordinating these two initiatives, the CMU and sustainable finance, Europe might be able to make faster progress in meeting both goals.

Companies in Europe are trying to expand their activities in the growing sustainable economy, supporting their businesses’ transition to a more circular model. According to a recent survey by the European Commission (2016), SMEs in the region are already providing a variety of innovative sustainable products. Indeed, in sustainability-related sectors, Europe has a strong record of entrepreneurship. Many start-ups have developed solutions to environmental and social challenges, offering services to individuals, communities, businesses, and public administration (such as health care, mobility, cultural heritage management, energy efficiency, and smart cities).

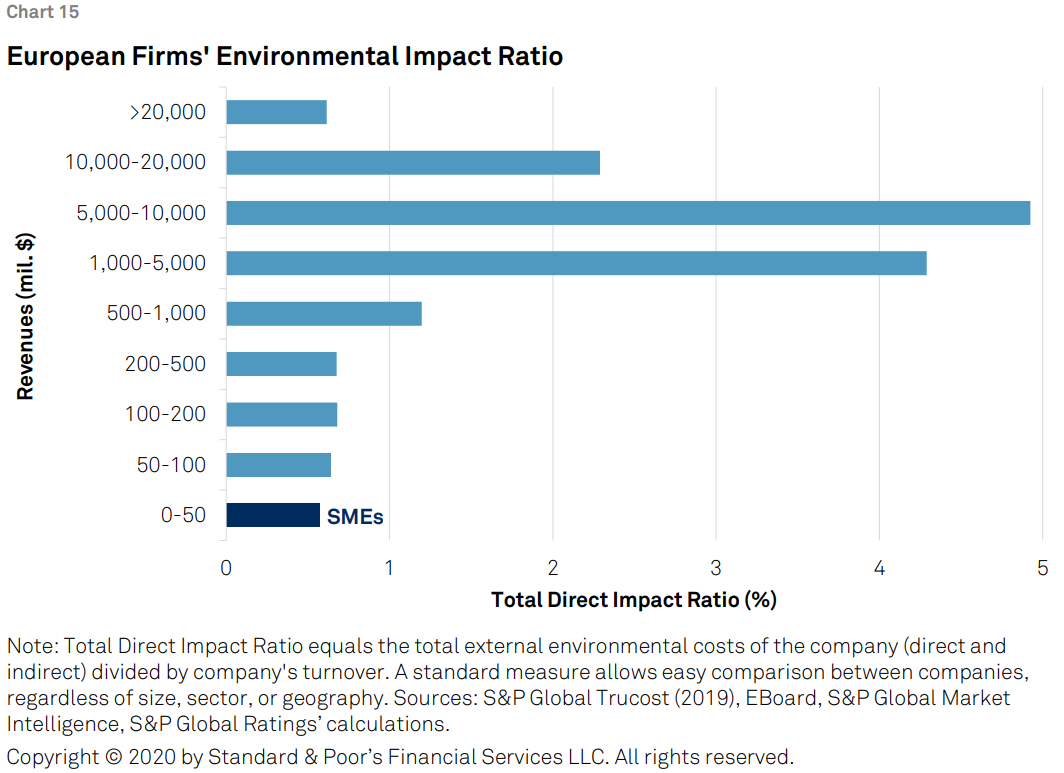

Large corporations offer many economic benefits, but from a strict environmental point of view, European SMEs appear to be more sustainable than large firms are. They generate lower external environmental costs (relative to turnover) than larger firms, according to data as of end-2018 by Trucost, part of S&P Global (see chart 15). Further analysis of the Trucost dataset indicates that SMEs are also “greener” in sectors with a higher environmental impact (such as utilities and materials). Because SMEs as a group have less environmental impact, the CMU’s goal of promoting and developing them would shift the EU economic fabric toward greener activities. That’s because, in the utilities and materials sectors, for example, they are less involved in industrial processes than large firms. Additionally, in the Trucost database, the density of SMEs is higher in industries with a lower environmental impact such as health care and real estate.

SMEs are typically embedded in their local communities. While markets are becoming increasingly aware of the relationship between environmentally and socially oriented companies and their profitability, there still is a shortage of metrics to prove such a relationship. This makes the social impact of SMEs (and companies in general) difficult to gauge.

Not surprisingly, most of these enterprises encounter difficulties in accessing early and growth financing. Their investment projects can often involve riskier technologies and a longer time to market. According to research from the ECB, capital markets may be better suited than banks to finance sustainable innovations that feature both high risks and high potential returns. In particular, public and private equity markets appear to play an important role in funding firms’ sustainable activities in various jurisdictions.

According to a 2018 report by the Sustainable Stock Exchanges Initiative, stock exchange activities to promote sustainability and transparency in their markets have grown significantly in the past two years, particularly in Europe.

The role of exchanges is key not only to enhancing companies' disclosure practices, but also in providing access to a wide and diverse range of investors. With equity traded on exchange platforms, SMEs would become more transparent not only to public equity investors but also to private equity firms and venture capitalists. For SMEs, a tailored regulatory framework and proper fiscal incentives would facilitate their access to capital markets. The CMU would therefore be a catalyst for favoring the transition from bank lending to capital-markets financing for sustainable SMEs. The creation of a centralized European exchange, in a virtual or physical form, could serve this purpose.

A limitation of the European capital markets is the information asymmetry between suppliers and users of capital, where reliable data about the financial and operational profiles of SMEs is not generally available. If not properly addressed, this information gap would prevent any form of capital market solutions for European SMEs, whether they are green bonds, SME securitizations, minibonds for SMEs, or public and private equity market funding.

Europe is at the forefront of credit information sharing systems, having also recently implemented the ECB's AnaCredit regulation. It mandates that banks collect granular reference and credit risk data on companies’ loan exposures above €25,000 (based on the harmonized ECB statistical reporting requirements), a reporting threshold low enough to cover the majority of European SMEs. Evidence from the World Bank (2019) shows that firms, particularly SMEs in countries with credit information systems, are less likely to identify access to finance as a major constraint and display lower default rates and higher operational efficiency.

For now, access to Anacredit is quite restricted. Making this unique European reference and credit dataset available to a broader range of markets participants could increase transparency about SME financing.

To date, the EU has completed some 20 of the 33 measures in the 2015 action plan for the CMU. Regulations on venture capital, covered bonds, and European pension products have been finalized. Important action plans for fintech and sustainable finance have moved forward. Some of the measures have been criticized for not going far enough or being subject to significant political compromises, for example, the directive on preventive restructuring. Moreover, Brexit could dent European ambitions, considering that equity finance and expertise is more developed in the U.K. than on the Continent. The U.K. is home to about 20% of Europe's private equity firms and accounts for half of the funding raised by the European industry. Finally, the last "Survey On The Access To Finance Of Enterprises" (SAFE) by the ECB, focusing on SMEs, does not suggest any significant shift toward equity financing.

The view from S&P Dow Jones Indices

Over the last decade, a more balanced allocation toward equity markets instead of bank deposits, as proposed under the CMU, would have increased the return of EU savings. For instance, the S&P Europe 350 Index's compound annual growth rate (8.76%) outperformed European cash rates (0.21%; see chart 16). The S&P Europe 350 Index, launched in October 1998, serves as a benchmark for the large capitalization European stock market. As we analyze below, its performance has also been superior to that of the majority of actively managed European large capitalization equity portfolios.

The report by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) on the performance and cost of retail investment products notes that if the CMU is to meet the objective of successfully encouraging greater participation by retail investors in EU capital markets, clear, comprehensive and comparable information about investment products is a critical component. The same report notes that the performance of active funds available in Europe, partly due to higher fees, is poor compared with passive funds.

We would go further and posit that, due to survivorship bias, the performance of active funds is actually worse than it appears in ESMA's analysis. Europeans might be able to participate more fully in the wider global trend toward low-cost, diversified access to equity markets if it were simpler, easier, and efficient to do so.

Numerous observers have found that most actively managed equity funds typically underperform passive benchmarks. One of the earliest studies of active management dates from 1932 (“Can Stock Market Forecasters Forecast?”), although academic commentary began to proliferate in the 1970s (for example, see "A Random Walk Down Wall Street," and “The Loser’s Game”). Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson’s evaluation of active portfolio managers in the 1974 article “Challenge to judgment,” was especially harsh: “a respect for evidence compels me to incline toward the hypothesis that most portfolio decision makers should go out of business—take up plumbing, teach Greek, or help produce the annual GNP by serving as corporate executives.” Interestingly, John Bogle credits Samuelson's article with inspiring him to start the first index mutual fund at Vanguard in 1976.

S&P Dow Jones Indices has contributed to this literature by producing SPIVA® (S&P Index Versus Active) reports for the European fund industry since 2013. These compare the performance of actively managed mutual funds domiciled in Europe to their respective benchmarks. Among other statistics, the reports measure the percentage of funds (available one, five, or 10 years ago) that outperformed their respective benchmarks. Across half a decade of such reports, it is clear that most active funds underperform most of the time. For example, of 1,322 funds included in the most recent report and categorized within the pan-European equity category and denominated in euros, only 156 (12%) outperformed the broad-based S&P Europe 350 Index over a 10-year period.

While other studies typically do not control for survivorship bias, we believe it is essential to do so. As illustrated below (see chart 17), in many categories, a significant proportion of the active funds available 10 years ago did not survive the decade. Naturally, individual fund survivorship correlates positively with performance (because poorly performing funds often close), which means that performance statistics for surviving active funds are biased upward.

The relatively high long-term underperformance rate of active European equity funds is not unusual or even unexpected. Simple arithmetic indicates that the average market participant will achieve the market return, while the compound effects of costs and fees bias the average performance of active funds downward over time, according to a study by William F. Sharpe. Similar reports produced by S&P Dow Jones Indices for the U.S., Canadian, Indian, Asian, Australian, Japanese, South African, and Latin American fund markets have offered similar results. All around the world, investment funds following a low-cost index-tracking strategy have a decisive performance advantage over active management. These results are not statistical oddities. They occur for good reasons, and therefore should be expected to persist (see “Shooting the Messenger,” S&P Dow Jones Indices, December 2017). This makes it even more remarkable that only a relatively small percentage of European investors use index funds to invest in equities.

As a proportion of the overall fund landscape, the market share of "passive" or index-tracking funds stands at just 16% in Europe according to a 2019 study by Broadridge, compared with over 50% for equity-linked U.S. mutual funds according to a Bloomberg report based on Morningstar data. However, it is widely expected that regulation to date, including MiFID II, will lead to enhanced growth in passive vehicles. Based on current sales and growth figures, a passive share of 30% is likely in the next decade, with an increasingly significant proportion of the total contributed by exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

While other regulations and trends within the finance industry – particularly the compensation structures for intermediaries selling or advising retail investors about their allocations – may have a greater role to play, several aspects of capital market trading could support the adoption of low-cost, transparent products such as index funds. These include:

Creation of a consolidated tape and coordinated "European" equity close

Equity indices typically calculate the end-of-day index levels on the closing price of the index constituents’ share prices, as reported by their primary exchange. However, since the exchanges do not all close at the same time, the result can be a blend of prices reported at different times. Moreover, for index constituents traded on more than one market, the closing price associated with one exchange may be very different than another's. This creates the potential for confusion among investors and a lack of transparency on the true price and volume for each security.

A consolidated European tape – aggregating the trades in each security across all exchanges, dark venues, and over-the-counter trading – became possible for both stocks and ETFs with the introduction of MiFID II and its associated reporting requirements.

Enhancement of the European Best Bid And Offer

With the introduction of a consolidated tape available to market makers and brokers, the provision of price transparency around execution will become much simpler. It would also allow for consideration of more stringent requirements of brokers. For example, beyond a requirement to communicate the current best prices, market makers could be required to offer their customers a price quote that is at least as good as the currently quoted prices on the consolidated tape (for the appropriate size), and brokers to transact at the best available prices.

This might ease the minds of retail investors when making allocations to ETFs in particular – where the purchase or sale price they receive (gross of commissions) can be different than the price they might be watching on an exchange's website.

While we have focused our attention on retail investors making long-term allocations, it should be noted that index funds can have wider applications, particularly if they are available to trade on the secondary market, as is the case for ETFs.

Although the sponsor may manage the underlying portfolio for an index-tracking ETF passively, holders of the ETF's shares may trade it actively. A recent study by S&P Dow Jones Indices based on products tracking its indices illustrated relatively high participation from active investors in those products: implied asset-weighted average holding periods typically were a few months, with many traded more actively. (See "A Window on Index Liquidity,” S&P Dow Jones Indices, August 2019.)

While there are already ETFs and other index-linked products such as futures and options available for active investors to trade in Europe, enhancing their transparency should help improve the ability of those active participants to express their views regarding market segments (sectors, countries, etc.) and thereby increase liquidity and efficiency across the complex of exchanges and listings in Europe.

We believe the CMU has the capacity to turn the economic and financial tides in Europe by:

All of this would help boost economic growth in the EU. Absent progress toward completion of the CMU, we believe it could be more difficult to break the vicious circle of high debt and low trend growth, with EU savings increasingly flowing abroad to finance investment in non-EU countries.

Content Type

Location

Segment

Language