Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Language

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

All countries are exposed to demographic transitions, but some will be impacted much sooner than others. Governments must take timely policy action if they are to adequately address the consequential challenges.

Published: January 10, 2024

By Samuel Tilleray, Marko Mrsnik, and Ken Wattret

Highlights

Most countries will experience a demographic shift over the coming decades due to falling birth rates and longer life spans.

This change will likely lower real GDP growth and increase budgetary challenges. The extent of the demographic shift, and the capacity of governments to deal with it, is heterogenous across countries.

While governments will have difficulty in reversing demographic trends, their ability to cap the fiscal risk is more achievable provided policy action is decisive and timely.

Worsening demographics is not a new issue, but its relevance to governments and public finances is growing. Populations are getting older in all 80 rated countries analyzed by S&P Global Ratings, although the intensity of this demographic shift is uneven. We identified 18 countries where by 2035 the elderly population relative to the working-age population (the old-age dependency ratio) will have increased by at least 50%.

By 2035, the demographic shift will be the most significant in five East and Southeast Asian economies — Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore, Thailand and mainland China. There will be more than two additional elderly people for every 10 working-age residents in these jurisdictions, a near doubling on average of their existing elderly population relative to the working-age population. That these five start with lower shares of elderly in their populations is only partially mitigating, as the aging process will not stop in 2035. The rapid change in these countries’ age profiles suggests that care will need to be taken that existing benefits and revenue sources do not face a risk of sudden disruption.

Six countries in our analysis were likely to see their old-age-dependency ratio worsen by less than 1 percentage point, of which five are in sub-Saharan Africa. The birth rate is still high in much of the region, giving them more time to adapt their social security systems.

Labor, capital and productivity growth are the three components of long-term growth, so a shrinking supply of labor will pressure real GDP absent other changes. As faster capital accumulation is unlikely to be sustained for a prolonged period, particularly in advanced economies, much will depend on technological development and its impact on productivity. The expected decline in the world’s labor force will therefore need to be offset by, for instance, widespread adoption of AI technologies to maintain current growth rates.

Yet, historically, such transformative technological changes have not usually created a persistent change in productivity growth after an initial boost. The implication of the world’s changing demographics is clearly of macroeconomic importance as well as being fiscally challenging to governments.

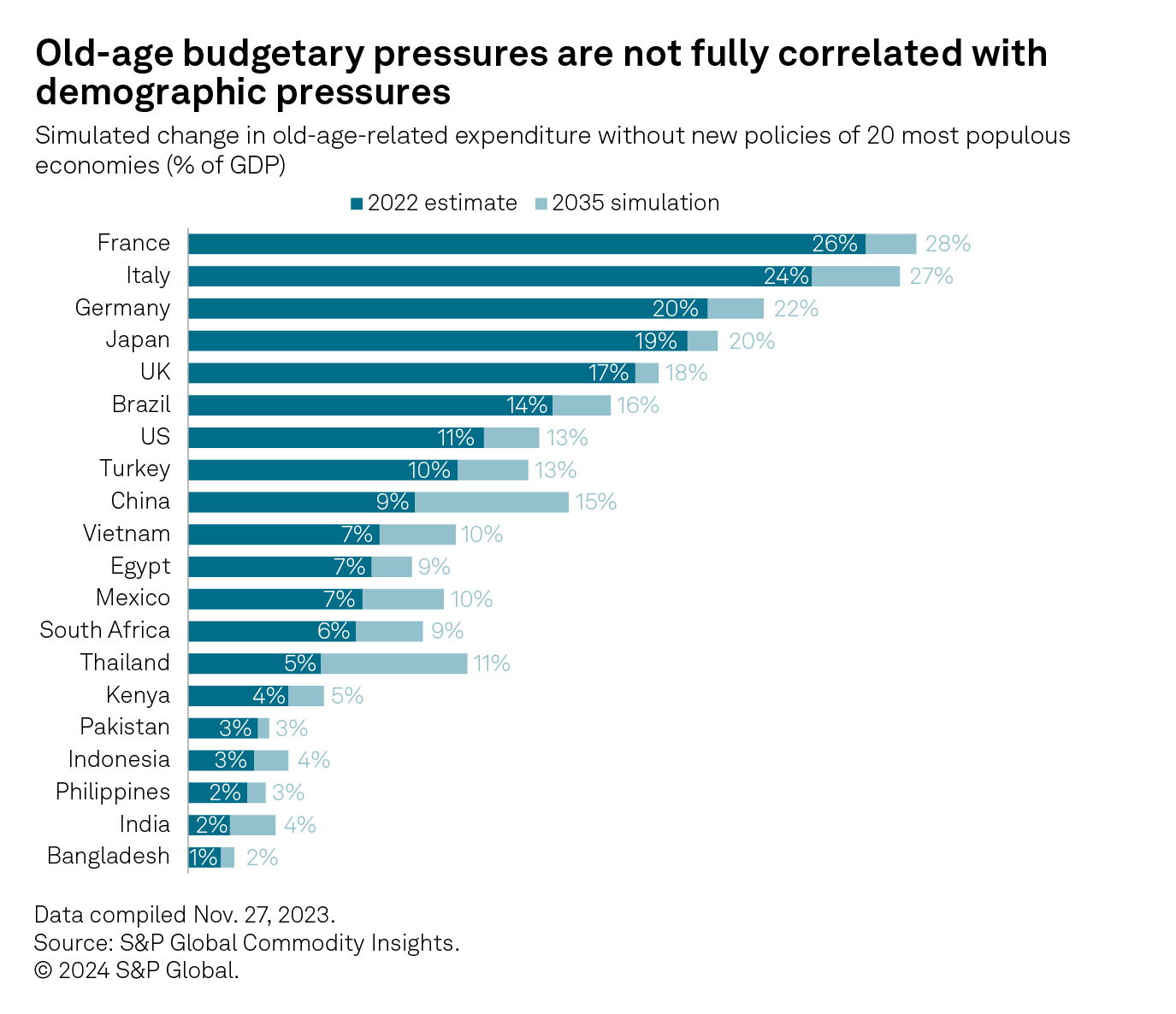

Aging populations are a formidable challenge for the public purse as social security systems in many sovereigns are likely to prove unsustainable without policy changes. Pension outlays have been the focus of policy action, but it has become increasingly clear that healthcare spending is at least as important. Understanding their relative composition is paramount to understanding medium- and long-term budgetary pressures. Age-related expenditure includes pensions, healthcare and long-term care. Spending on these items varies massively across regions, with Western and Northern European countries spending an average 19.1% of GDP in 2022, compared with just 2.3% of GDP in sub-Saharan Africa.

In terms of total spending on age-related items, advanced economies are already significantly more burdened than the rest of the world. Countries facing the largest increase in budgetary pressure from this spending are all challenged by a faster demographic shift. Our analysis found that spending growth on these items will increase most intensely in mainland China, South Korea and Thailand. On average, these three governments could be forced to dedicate an additional 5.7% of their GDP to age-related expenditure by 2035, absent any policy change. Family is a key provider of long-term care in these countries, and an important mitigant of related budgetary pressures in the near term. The largest part of related responsibilities falls on women, so as female labor participation increases, pressures for institutionalized support will likely trigger additional demand for government spending.

Over the next decade, advanced economies will remain well ahead in terms of age-related spending, but emerging market economies will be under increasing budgetary pressure from their aging societies. It is possible that a significant number of people will get old before they get rich. The budgetary implications of these shifts appear more forecastable given the set social security parameters, while the macroeconomic implications of such a shrinking in the relative labor force is less clear and could undermine emerging markets’ aspirations to achieve higher-income status.

Governments in Colombia and Chile are under significant budgetary pressure owing to their shifting demographics. This is despite a somewhat less intense demographic shift compared with the Asian economies already discussed and reflects the relatively more generous state support for the elderly in terms of pensions and healthcare. Without corrective or offsetting policy actions, by 2035, we expect the Colombian government will need to find 5.3% of GDP to support older populations, and the Chilean government 4.5%.

Gulf countries are likely to start experiencing aging pressure if generous state benefits continue. Saudi Arabia is one country where pressure appears most intense over the coming decade, and Qatar’s age-related spending will more than double, albeit from a much lower base. The coming decade is likely to be just the start of Gulf countries’ transition; our simulations out to 2060 imply demographic pressure could seriously cumulate in the region in the years after 2035.

European governments are likely to remain the world’s top spenders on age-related items.

Generous state-led social security systems along with universal government-provided healthcare leave the region’s governments structurally exposed to their populations’ demographic shifts. The pass-through of these demographic shifts to government spending is not one-to-one. Aging Greece, the fourth-oldest country in our sample, is projected to see a decline in age-related expenditure by 2035. This reflects significant structural reform taken by consecutive Greek governments, which has effectively reduced benefits. One example is the elimination of a large part of a pension’s automatic indexation. The future challenge for the government may relate to adequate provision of social security benefits rather than to their financial sustainability. Several central and Eastern European governments, such as Romania and Slovenia, have taken insufficient action to fully shield public finances from their worsening demographic profiles, and further reforms are warranted.

Active efforts to boost employment rates among older groups have been an important offset to deteriorating demographics. Japan stands out for being head-and-shoulders above all other countries in terms of demographic transition; 29.2% of the population are aged over 65, and a further 1 in 10 are over 80. The skew of the population has been partially offset by increasing employment rates across older age groups over the past decade. This was achieved by pushing out retirement ages, encouraging reemployment among the older population and efforts to improve female labor market participation. In the context of Japan’s relatively rigid migration policy, this has slowed the depletion of its workforce.

Our framework suggests governments can deal with future imbalances in three main ways:

Through structural reforms aimed at raising employment levels for older workers and raising potential economic growth

By front-loading a sustained budgetary consolidation

Through substantial reforms to social security and publicly funded healthcare systems that go beyond most governments’ initiatives so far

While migration can cushion the budgetary impact of population aging, alone it is unlikely to be sufficient to fully offset it. Firstly, the number of migrants is unlikely to be sufficient to compensate for the decline in the population. While the migrant workforce is at first a contributor to growth and social security revenues, it burdens the budget in the same way as the host population as it reaches retirement age, all other things being equal. Finally, where the fertility rates of the migrant population are relatively high compared to those of the host population, over time they converge as the migrant population adapts to the host country’s fertility patterns and the population growth of the migrant population reduces.

Given the growing urgency of tackling the budgetary implications of population aging and the capacity of governments to influence the outcomes of policy, the latter two options in the list above appear most realistic in the near term. Which of these reform approaches, if any, governments decide to invest their political capital in to maximize the beneficial impact on fiscal solvency depends on the specific circumstances in each country.

While significant progress has been made in reforming social security systems, especially among advanced sovereigns, many potential political stumbling blocks remain. Total age-related spending in a typical advanced sovereign today represents more than 55% of a government’s total primary spending (total government expenditure without interest payments, including spending on education). This implies that the related spending items will be an important part of any government’s budgetary strategy, especially if, as is currently the case, it is aimed at reducing budget deficits following the two consecutive economic shocks since 2020.

Rationalizing public pension and healthcare systems can, if embraced early, help spread the impact of such unpopular policy measures over an extended period, with the consequently lower burden of adjustment shared across generations of taxpayers and voters. Such policy behavior is important for managing the expectations of economic agents, avoiding sudden policy shifts that could alienate electorates or undermine economic growth performance.

Besides the need to ensure adequate social transfers to reduce the risk of poverty, the ongoing demographic shift will affect the age structure of electorates, which could make the political climate for pension and healthcare reform more difficult.

For emerging market sovereigns, the policy issues are also complex. Population aging will likely take place against a backdrop of relatively high rates of economic growth. This growth, coupled with greater economic convergence with today’s more prosperous sovereigns, should make the social and fiscal pressures arising from population aging relatively more manageable. These governments may have more time to consider their policy options than today’s more economically advanced sovereigns, but they will still need to design fiscally sustainable programs as their populations continue to age, especially given the widening of the pension and healthcare system coverage in several sovereigns. Already, following the substantial policy activity among the advanced sovereigns, our analysis suggests that the need to tackle the outstanding challenges is as pressing for many emerging market sovereigns as it is for the sovereigns in advanced economies.

Next Article:

Can generative AI create a productivity boom?

This article was authored by a cross-section of representatives from S&P Global and in certain circumstances external guest authors. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any entities they represent and are not necessarily reflected in the products and services those entities offer. This research is a publication of S&P Global and does not comment on current or future credit ratings or credit rating methodologies.

Content Type

Language