Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Language

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Investments in adaptation must close the gap with mitigation financing to avoid the worst outcomes.

Published: January 13, 2023

Highlights

Adaptation to climate change will become as important as climate mitigation in terms of protecting wealth and lives over the next few decades. Accelerated investments in adaptation finance will be needed to avoid the most severe impacts, and there are signs those investments may be at a turning point.

The physical impacts from climate change are increasing, and the window of opportunity for building resilience and adapting at lower costs is closing rapidly.

Agreements reached at COP27, including the go-ahead for a “loss and damage” fund for developing countries and the Sharm el-Sheikh Adaptation Agenda, which describes 30 actions needed by 2030, will build on other initiatives and serve as catalysts through which investments in adaptation and resilience projects can gain significant traction.

The pace of change over the coming years will likely accelerate, driven by the realization and inevitability of climate impacts as well as the market-based incentives starting to emerge.

Countries, companies and communities are going to have to face the impacts of acute physical risks related to climate change as global emissions and temperatures rise. Still, these effects will not be evenly distributed. Lower- and lower-middle-income countries are more at risk than wealthier peers, even though they have contributed less to climate change and are less ready to cope. Lagging investment in the technologies and interventions needed for adaptation is also widening the gap. With this in mind, adaptation will become as important as climate transition financing in terms of protecting wealth and lives over the next few decades. Accelerated investments in adaptation finance will be needed to avoid the most severe impacts, and there are signs the quality and amount of funding being deployed, including from the private sector, is nearing a turning point.

Physical effects from climate change are occurring, and the impact is rising. In 2022, the U.S. saw at least 15 disasters resulting in $1 billion or more in damage, extending a growing trend since the 1980s, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. S&P Global Ratings recently estimated that home and office insurance claims in the U.S. rose 5.7% year over year to $148 billion (as measured in direct premiums written) in 2021. Global average annual insured losses attributed to natural catastrophes (affecting all property-related lines) increased to approximately $96 billion in 2017-2021 from $21 billion in the prior five years, according to Munich Re. Rising losses are likely driven by increases in the severity and frequency of extreme weather events as well as a greater number of assets located in vulnerable areas. S&P Global research and other climate studies, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s latest assessment report (AR6), point to worsening economic losses even under low-emission scenarios in the absence of a significant uptick in adaptation investments.

About 4% of global gross domestic product could be lost annually by 2050, according to S&P Global Ratings research, surpassing the 3.3% contraction caused by COVID-19 in 2020. The S&P estimate was based on an assessment of 135 countries’ vulnerability to and readiness for climate change over the next 30 years. It used a scenario (RCP4.5) that assumes countries deliver on current emissions reductions commitments as per their nationally determined contributions (see chart 1).

Chart 1

The adaptation challenges facing individual countries — and, by association, companies — differ because of the varying frequency and severity of climate hazards, such as storms and wildfires. The vulnerability of assets also differs by location and asset type. Still, adaptation measures can help companies and countries withstand climate risks. Japan, for instance, has avoided large wealth damage even in the face of high climate risks, including typhoons. Lower- and lower-middle-income countries have less ability to cope with and adjust to damaging events, leading to higher and more persistent economic losses. This highlights the importance of international cooperation to support equitable distribution of adaptation investments, particularly given that those most at risk have contributed comparatively little to climate change. A compounding problem is that the finance available to support countries’ adaptation to physical climate risks is severely lagging what is needed. Furthermore, even ambitious investments in adaptation will not fully avoid climate-related impacts.

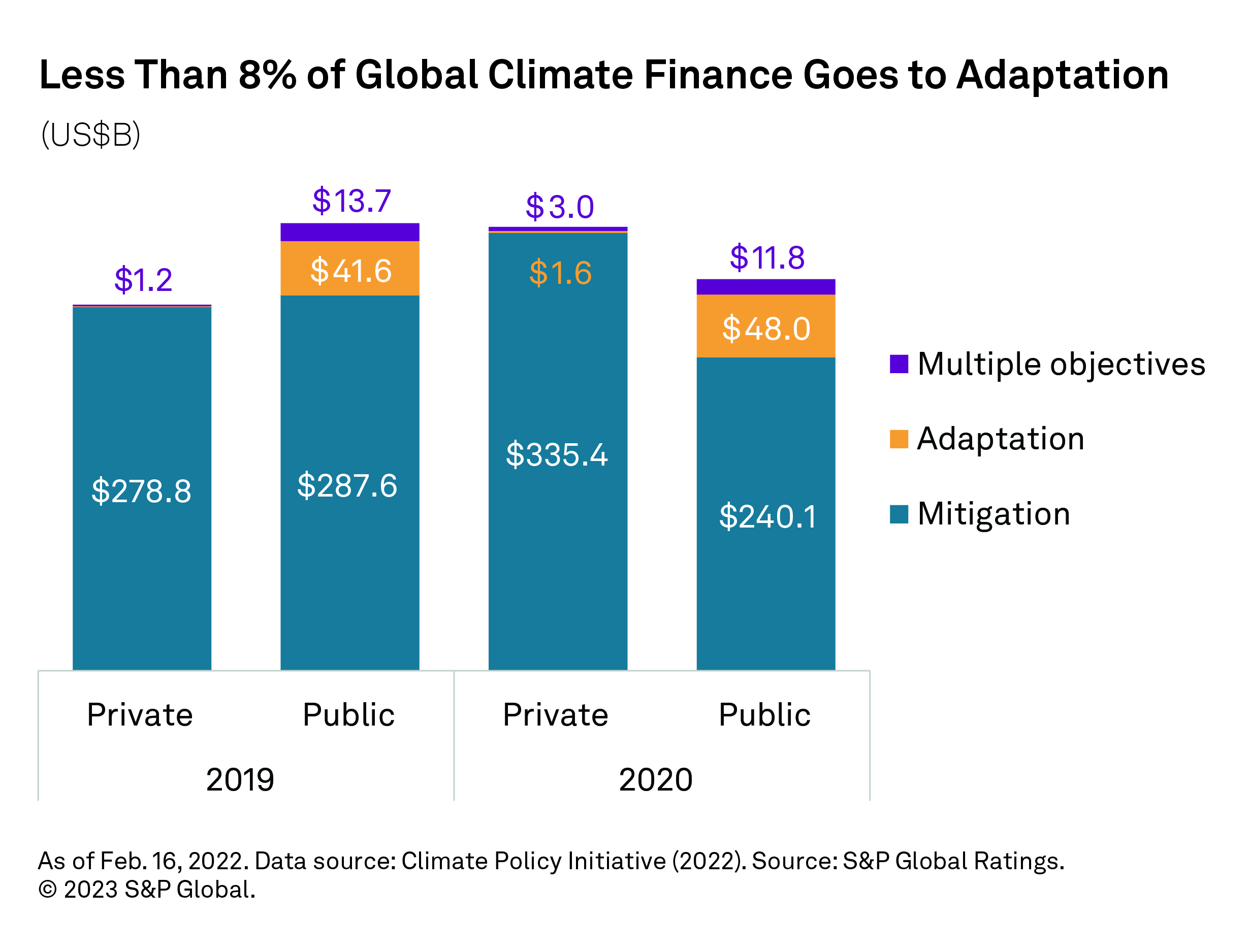

Annual adaptation costs for developing countries, accounting for inflation, will be in the range of $160 billion to $340 billion by 2030, and between $315 billion and $565 billion by 2050, according to the United Nations’ Environment Programme (UNEP) Adaptation Gap Report 2022. In contrast, only about $83 billion of climate finance, covering both adaptation and mitigation, was mobilized in 2020, missing the $100 billion-per-year pledge made by developed countries to developing countries under the Paris Agreement on climate change. The picture is similar when looking at global climate finance flows, where mitigation finance dominates, as reported by the Climate Policy Initiative (see chart 2).

Chart 2

Instruments such as green bonds could partly refocus financial flows toward climate-positive outcomes helped by initiatives such as recent guidance from the Global Center on Adaptation. However, while green bond issuance has increased fourfold since 2018 — surpassing the $3 trillion total issuance mark earlier this year — most green use of proceeds and sustainability-linked bonds are focused on mitigation, with adaptation and resilience accounting for only 4% of green bond spend last year (see chart 3).

Chart 3

The challenges associated with scaling adaptation and resilience finance to the levels required are clear.

Despite these challenges, there appears to be growing interest from market participants in financing adaptation and resilience projects. Financial instruments such as privately issued climate resilience bonds, debt-for-climate swaps, public-private partnerships and infrastructure investment trusts are likely to go some way toward plugging the growing adaptation gap. Large institutional investors including JPMorgan Chase, Nuveen and Wellington already have dedicated adaptation investments in their climate or impact funds (which exceed $1 billion). In 2022, The Lightsmith Group closed a $186 million private equity fund dedicated solely to adaptation, as reported by Global Adaptation and Resilience Investment (GARI).

At the 2022 COP27 conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, there were also calls for more investments in adaptation and resilience, at a time when the window of opportunity to stop the worst impacts of climate change is rapidly closing. We believe that agreements reached at COP27 — including the Sharm el-Sheikh Adaptation Agenda, which describes 30 adaptation actions needed by 2030 — and ongoing initiatives like the Global Goal on Adaptation (established under the Paris Agreement) and Race to Resilience (agreed at COP26) will serve as catalysts through which investments in adaptation and resilience projects can gain traction through 2030. This trend will accelerate amid a growing focus on companies and governments that do not take sufficient action to adapt and build resilience to the physical impacts of climate change. Analysis by S&P Global Sustainable1 shows that 92% of the world’s largest companies have at least one asset highly exposed to a climate hazard by the 2050s.

In tandem, growing familiarity with, and availability of, climate risk data, improvements in understanding the uncertainties associated with such datasets, efforts to standardize terminologies and the use of specialist labels in the market may partially help to turn the tide against the impacts of the most severe warming scenarios.

The physical impacts of climate change will increase over the coming decades — even if the world makes significant progress in cutting global greenhouse gas emissions — due to the lag in the climate system between emissions reductions and global temperature change. The opportunity to build resilience and adapt to the worst impacts of climate change is also fading as emissions increase each year. Companies and countries are waking up to a future of more frequent and extreme physical climate risks and growing commitments (and costs) associated with mitigating emissions. We believe that this dawning reality will render adaptation finance as important as transition finance in protecting wealth and saving human lives in the coming decades. The pace of change over the years ahead will likely be driven by the realization and inevitability of what is happening as well as market-based incentives that are already emerging.

Storm Clouds Or Clear Skies Ahead: How Rising Insurance Premiums From Environmental Physical Risks Could Affect U.S. RMBS And CMBS

Weather Warning: Assessing Countries’ Vulnerability To Economic Losses From Physical Climate Risks

Global Reinsurers Grapples With Climate Change Risks

Keeping The Lights On: U.S. Utilities’ Exposure To Physical Climate Risks

Model Behavior: How Enhanced Climate Risk Analytics Can Better Serve Financial Market Participants

Damage Limitation: Using Enhanced Physical Climate Risk Analytics In The U.S. CMBS Sector

Scenario Analysis Shines A Light On Climate Exposure: Focus On Major Airports

Better Data Can Highlight Climate Exposure: Focus On U.S. Public Finance

Sink Or Swim: The Importance Of Adaptation Projects Rises With Climate Risks

Next Article:

The EV Revolution – Moving From Oil Age to Battery Age? >

This article was authored by a cross-section of representatives from S&P Global and in certain circumstances external guest authors. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any entities they represent and are not necessarily reflected in the products and services those entities offer. This research is a publication of S&P Global and does not comment on current or future credit ratings or credit rating methodologies.

Content Type

Language