Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Language

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

This technology has profound implications for labor markets, the global economy and equitable development.

Published: January 10, 2024

By Sudeep Kesh, Shankar Krishnamurthy, and Nick Patience

Highlights

Generative AI (GenAI) can accelerate human potential, aid in job creation and augment human labor and intelligence in a way comparable to the impact of mobile devices and the internet over the last 25 years.

GenAI is a leap forward in AI that creates fear and optimism in equal measure about the future of jobs and labor markets. While automation and AI have been around for decades, what sets GenAI apart is its ability to “generate new content” and for humans to “interact with it using natural languages.”

GenAI will be a net positive for labor markets and the global economy. It will enable sizable productivity gains, amplify job creation and stimulate investment in technologies that enable humans to measure what they cannot naturally, yielding more inclusive and sustainable development than ever before.

Generative AI (GenAI) has the potential to augment and accelerate human intelligence, facilitating productivity in unprecedented ways and even generating work that was not possible without the technology. Much attention and focus should be given to using such technologies in ways that benefit society through ethical, inclusive and fair means, allowing these innovations to fuel human progress.

Historically, technology, specifically automation, elicited fear of job losses as machines took over repetitive tasks performed by humans, increasing productivity and eliminating some jobs altogether. Those same technologies also created new jobs. The rate of technology adoption has accelerated since the days when steam engines catalyzed the first industrial revolution, and the more recent fourth industrial revolution was supercharged by the convergence of digitalization, the internet, smartphones, the internet of things and AI. To paraphrase American computer scientist Ray Kurzweil’s “Law of Accelerating Returns,” technological advances tend to build on themselves, increasing the rate of further adoption. The recursive properties of technology apply not only to technological development but to economic development as well.

Yet concerns about large-scale job displacement resulting from technological advancements are neither new nor invalid. Technology is a change agent, and some level of resistance to change is part of the human condition. Advancements such as digitalization, the internet and mobile technology have combined to create a net positive impact. According to Internet Association data, the sector accounted for 10% of US GDP and generated over 18 million direct and indirect jobs. The statistics mask the “how” and the “why.” Though the first e-commerce transaction was in the early 1980s, the launch of the World Wide Web in 1993 enabled the explosive growth of the internet as a viable medium by allowing web browsers to view textual information and pictures and, perhaps most importantly, to hyperlink content together using URLs. Before this, the internet was largely text-based, comprising digital messages and bulletin boards. In the late 1990s, the businesses that introduced e-commerce leveraged this technology to formulate new business models for conducting commercial activities, a “killer app” not dissimilar to ChatGPT and other forms of GenAI today. GenAI technology’s adoption process had many periods of rapid development followed by halts in implementation, similar to e-commerce. While not entirely new, technologies such as ChatGPT galvanized GenAI technology’s utility to end users, spawning widespread use and subsequent technological advancement in many similar technologies.

Similarly, smartphones, first developed in 1992 (IBM Simon), were largely dormant for a decade until the iPhone launched in 2007. This helped make the internet accessible to a much larger global population through apps, a new type of software distribution giving smartphone users a nearly infinite ability to customize their devices. Global internet penetration has reached 65.7%, with about 5.3 billion people having access to the internet and almost 90% using it via mobile devices, according to the “State of Mobile Internet Connectivity Report 2023.” The internet and mobile have helped democratize access to the digital economy, reducing the digital divide.

GenAI, too, has the potential to fundamentally transform the global economy and labor force. Much of the current focus concerns labor productivity, with productivity savings estimates ranging from 15% to 40%, raising questions about whether it will generate large-scale disruption of the labor market by displacing humans. History shows that productivity growth, powered by technology, has been a key driver of economic growth, creating new jobs and new industries as people and capital are increasingly at liberty to pursue more important, higher economic value outputs.

GenAI is already being used to automate tasks previously performed by humans. As AI-powered chatbots used in customer service roles become more sophisticated, fewer people are needed to answer basic queries, for example. While previous waves of automation affected those engaged in manual labor tasks, GenAI could encroach on tasks performed by knowledge workers, including data entry and data extraction, and by those deemed more highly skilled. This could lead to job displacement in sectors including retail, manufacturing and transportation. If it does, there could be unprecedented demand placed on governments to support reskilling, which would have a major economic impact.

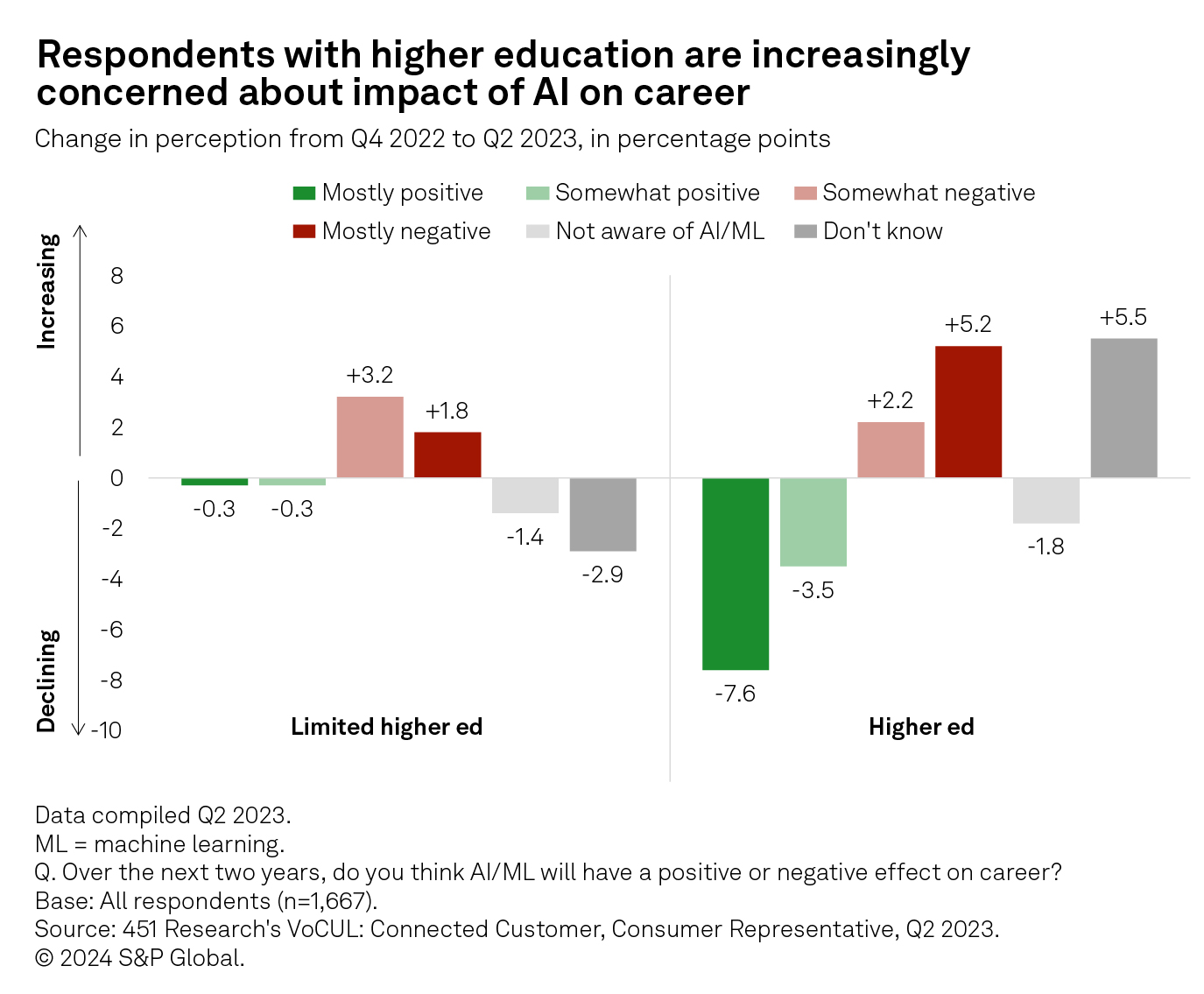

Worries are emerging among people who were not that concerned previously. S&P Global Market Intelligence’s 451 Research VoCUL: Connected Customer, Consumer Representative survey conducted in the second quarter of 2023 found the proportion of higher-education respondents that were “mostly positive” about the impact of AI on their careers decreased to 14% from 22% six months earlier, around the time that ChatGPT launched.1

Higher-education respondents’ net positive views fell to 12% from 31%, much more pronounced than the 16% to 11% decline seen in non-higher-education respondents.

GenAI can also augment human capabilities, making it possible for people to do their jobs more efficiently and effectively. AI-powered tools can help doctors diagnose diseases more accurately, and AI-powered software can help lawyers research and write legal documents more quickly.

The launch of Microsoft Excel in 1987 is a good example of how digitalization can impact the labor market. The number of US workers employed as bookkeepers and accounting clerks declined by about 500,000 to 1.5 million between the late 1980s and 2000, Morgan Stanley research using US Labor Department statistics shows. In the same period, the number of US workers employed as accountants and auditors rose to 1.5 million from 1.3 million, while management analysts and financial managers increased to 1.5 million from 600,000.

GenAI will create roles that do not currently exist and, in many cases, that we cannot even imagine — as has happened during past waves of technology adoption. The role of search engine optimization specialist emerged as marketing moved into the digital realm, as did professions in technology such as data scientist and machine learning engineer.

Of those surveyed by the World Economic Forum for its “Future of Jobs Report 2023,” “49% anticipate AI to be a catalyst for job creation, while 23% also expect it to drive job displacement. This doesn’t necessarily imply job elimination, but rather a shift in roles and the skills required to perform them.”

GenAI has the potential to replace or reduce the need for humans in certain jobs, such as ad creation, customer service and software code writing. These professions have already been affected by AI to some extent. What makes GenAI different from traditional AI is its ability to “create/ generate” new content. Coupled with its “natural language capabilities” and “multimodal interaction” (text, image, voice, etc.), it closely mimics human thinking and interactions. GenAI can also help accelerate the “creator economy” (e.g., jobs producing digital content). There are about 50 million people who consider themselves “creators,” but GenAI could significantly expand this in areas such as the arts, music and movies. With its natural language interface, GenAI has the potential to democratize access to AI, giving those who may not know computer programming the opportunity to interact in their native language with AI to create new products and services.

S&P Global believes that digital transformation will add roughly $7 trillion of additional debt to global capital markets by 2030, based on an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development report (see “Global debt 2023” to learn more). However, we also believe that GenAI could have a transformational economic impact on the following areas, and more:

Green energy transition: GenAI could be pivotal, especially with advancements in “under the hood” technologies such as machine learning, neural networks and network science, to develop new and better products that meet sustainable criteria. GenAI could also help with energy demand forecasting, optimizing power grids and shifting back to a circular consumption economy from a linear one. The International Energy Agency, as part of its “Net Zero by 2050” road map, estimates that 30 million more people will be working in the clean energy sector by 2030.

Education and reskilling: With its natural language capabilities, GenAI is an ideal tool to deliver training in local languages and help the world’s non-English-speaking population do jobs that require English language skills. This could significantly increase job market access and improve labor participation in developing countries, leading to more inclusive participation in global growth. GenAI could also create personalized tutors or coaches that focus on individual learning needs.

Agricultural technology: Agriculture could benefit from using the internet of things (devices such as sensors that enable tracking and monitoring of physical processes such as temperature, soil moisture, etc.), drone technology and GenAI to monitor crops, improve yields and optimize the farm-to-table food supply chain. A significant agrarian workforce could be retrained to develop skills and create new jobs such as precision agriculture analysts, drone pilots and sustainable development practitioners.

Healthcare: AI is still in the early stages of its true potential. As of October 2023, the Food and Drug Administration has approved only 171 medical devices that incorporate traditional AI functionalities, and none incorporating GenAI. The technology will play an important role across the sector, from disease diagnosis and epidemic prediction and management, to drug discovery and manufacturing, to developing personalized medicines and treatments.

It is important for individuals and governments to prepare for the changes that GenAI is likely to bring. This includes investing in education and training to help workers develop the skills they need to succeed in the digital economy, where jobs will require a mix of technical skills and human creativity and judgment.

As technology related to GenAI matures, dialogue surrounding its governance, ethics and proper regulation is crucial. This is underscored by the digital divide between developed and developing economies as well as geographic, demographic, education and income-based paradigms. How these are fed into AI algorithms could propagate unwanted bias, such as overrepresenting or underrepresenting a particular segment of society. For example, some AI-based police tools used to predict where and who will commit a crime have been criticized for generating bias by targeting low-income communities and discriminating by race. In short, there is a nonnegligible risk that implementing AI in some processes could increase inequalities and digital imbalances if not carefully governed.

Significant investment is required to explore and build robust data systems and IT infrastructure, meaning larger companies are more likely to have access to discriminative AI/GenAI-based technologies or to leverage their abilities. GenAI is likely to become the provenance of large, multinational companies operating in developed economies, particularly among well-educated, high-income populations.

However, there are technologies that help small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), particularly those with compelling business models, to compete with their deeper-pocketed, larger peers. Namely, the growing use of open-source and proprietary technologies is facilitating the completion of a number of business use cases through technical conduits such as integrations and application programming interfaces (APIs). For example, when Meta made a commercial version of its Llama-v2 LLM available to the public, it democratized access to this innovative technology, enabling the research community and smaller organizations to harness the potential of AI.

SMEs account for nearly 90% of businesses and 50% of worldwide employment, according to the World Bank. Formal SMEs contribute up to 40% of the national income of emerging economies. If such enterprises creatively apply AI in their business models, the access channel could be expanded through more equitable means, provided there is adequate education, infrastructure investment and regulation to protect those still “outside of the system.”

Google CEO Sundar Pichai said “AI is too important not to regulate, and too important not to regulate well.” The regulatory environment for AI is rapidly changing, with the EU releasing the AI Act — the world’s first comprehensive AI law — which, once effective, will set rules that establish obligations for providers and users, varied in risk level, as defined by the law. Similarly groundbreaking is a Chinese law aimed at regulating GenAI, effective August 2023. The US is taking a more decentralized approach. A number of elements in privacy legislation include provisions and protections through a combination of data privacy laws and algorithmic accountability and fairness standards. A call for federal privacy legislation was part of the Biden administration’s Executive Order issued Oct. 30, 2023, which also requested the developers of the most powerful models to share safety test results with the US government and to notify the federal government during the training process, among other provisions.

GenAI brings forth additional challenges related to intellectual property, which itself, even without considering AI issues, is subject to varying laws and standards and differing definitions and protections by jurisdiction. Perception is another challenge. Much of the content generated through creative GenAI functions has a quality or “realness” because of an emulation that originates within the observers’ brain. A similar principle has led to many successful court rulings in copyright infringement cases, in which a particular likeness between two works was partially dependent on the observer’s familiarity with another work (such as Ed Sheeran’s lawsuit win in May 2023).

Perhaps most insidious is the GenAI technology surrounding so-called deepfakes, which create a digital likeness through audio or video emulation to make it look like someone has said or done something they did not, using a combination of real content and synthesized content. Such technology has been weaponized in the Ukraine-Russia war and other conflicts. For example, likenesses of both Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Russian President Vladimir Putin have been shown in fake news conference videos in false acts of surrender, understandably causing confusion among their citizens as well as their combatants. This technology makes it easy to disseminate misinformation and is especially attuned to acts of cyber warfare.

We anticipate that AI regulation, currently in its infancy and likely to evolve substantially over the coming months and years, will blend factors including education, protection and regulation. Education provisions will likely set standards and provisions to promote safe and fair use of AI technologies. Protection provisions will likely include information and privacy protections for those with access to AI systems, as well as protections for those who do not, as deleterious consequences stemming from misuse or malicious use of AI can have broad societal implications. Finally, regulation will likely need to balance the need for growth of technology in ways that promote equity, inclusion and fairness without constricting the ability of the technology itself to grow, the push-pull nature of which is often a byproduct of technological advancements more generally.

Next Article:

Global debt 2030: Can the world afford a multifaceted transition?

1Sampling is representative of the US online population aged 18 and over across multiple demographics: age, gender, household income, ethnicity and geographic region. Sample size: 5,000. See the full survey here (subscription required).

This article was authored by a cross-section of representatives from S&P Global and in certain circumstances external guest authors. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any entities they represent and are not necessarily reflected in the products and services those entities offer. This research is a publication of S&P Global and does not comment on current or future credit ratings or credit rating methodologies.