Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Language

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

Featured Products

Ratings & Benchmarks

By Topic

Market Insights

About S&P Global

Corporate Responsibility

Culture & Engagement

S&P Global Platts — 28 Apr, 2020

Headline oil prices in the US may have crashed briefly into negative territory last week, but even in the wreckage of the current economic crisis there is some hope.

Eventually, demand for fossil fuels will return once coronavirus pandemic lockdowns begin to ease. When consumption does resurface, the global oil industry will look very different, however.

At the heart of the current meltdown is Cushing, Oklahoma. The landlocked point on the map of America where a tangled web of pipelines comes together, bringing crude in from across the country to store in giant tanks.

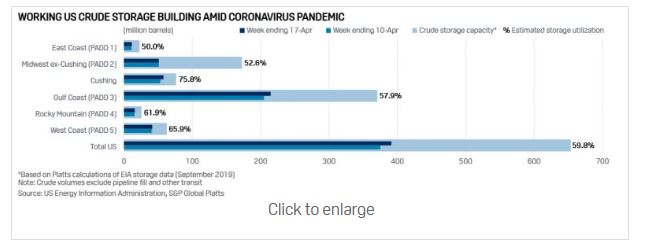

The problem is that Cushing’s capacity to hold 80 million barrels of oil is running out fast, squeezing a physical market where still too much crude is being produced to meet demand, which has plummeted catastrophically.

According to S&P Global Platts Analytics, consumption of oil is expected to fall by almost 20 million b/d, or about a fifth of last year’s levels, by next month. It could be more. This chronic imbalance between supply and demand means that Cushing’s acres of storage tanks, currently holding over 60 million barrels, could be completely full in three weeks.

At this point, oil producers across the US may have no alternative other than to shut down their wells by literally turning off the spigots.

Oil producers everywhere face the same problem to a certain degree, but in the US – where operating costs are high and the market depends on storage hubs like Cushing, which has been filling up at a rate of 6 million barrels per week as activity in refineries drops to a 17-year low – the situation is approaching a tipping point. Hundreds of debt-laden small producers across Texas and the Midwest, which have led the so-called US shale revolution, now face bankruptcy.

Although the companies may be insolvent, their assets will remain. These wells will be seized by creditors, or snapped up by larger and more financially stable competitors. Still, it is unlikely that US production levels can be maintained at current rates, especially if commercial storage hubs likes Cushing are filled to their brim.

By the US government’s own estimates, the country’s output will fall by 660,000 b/d by next year, from a peak of around 13.2 million b/d. However, these forecasts now look too optimistic unless America’s economy is forced out of its lockdown-induced hibernation. Even then it’s unlikely that consumers will restore demand back to previous levels immediately.

“Ultimately lower oil prices is what we’re going to have to have in order to stop more of the activity in the US shale producers, who right now are still producing relatively high amounts of oil, even though they’ve cut the capex, even though they’ve cut the rig counts, and the frack crews, none of that impacts today’s production unless you really start closing in existing wells,” said Chris Midgley, global head of analytics at S&P Global Platts in a recent research note.

“And eventually at these sorts of prices, you may well see producers choosing to close in their wells, see more Canadian production be closed in, or shut in, as we call it, and eventually seeing that help balance the market,” he said.

Some influential industry figures argue the damage to the oil market was done by OPEC even before the impact of the coronavirus on demand was fully understood. The breakdown of the alliance between Saudi Arabia and Russia earlier in the year resulted in the cartel’s biggest producers launching a ruinous price war to flood world markets with cheap crude.

Perhaps seeing the danger too late, US President Donald Trump tried to intervene to bring both sides back to the table this month and agree historic output cuts. In theory, their pact may have removed almost 15 million b/d from global supply, but it will take weeks for this to translate to markets. Meanwhile, the growing list of crude and refined product benchmarks trading close to negative levels suggests lasting damage may have been done.

“I think OPEC by flooding the market, in an oversupplied market, that was what spoiled the market, and then you had the pandemic on top of that,” said Qatar’s energy minister, Saad al-Kaabi, in an interview with S&P Global Platts. “It was like the Americans say, a double whammy, and will take the market a long time to recover.”

What will emerge from this mess is uncertain. Saudi Arabia and its OPEC partners are under huge pressure again to rein in their output further. But these countries, which in many cases require oil prices trading above $80/b to balance their budgets, are facing mounting economic problems at home.

Meanwhile, international oil companies such as Shell, BP and Exxon Mobil are cutting their investment spending on new production and hunkering down for a prolonged period of economic uncertainty. Some have already cut their dividends.

As in previous down cycles the collapse in spending across the industry and lower returns for investors will leave consumers exposed to more price volatility once the crisis abates. Uncertainty is about the only thing oil markets can be certain about in the future.