Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Our Methodology

Methodology & Participation

Reference Tools

S&P Global

S&P Global Offerings

S&P Global

Our Methodology

Methodology & Participation

Reference Tools

S&P Global

S&P Global Offerings

S&P Global

Apr 26, 2022

In pursuing energy transition policies, some mature petroleum jurisdictions may be on the cusp of turning old liabilities into new opportunities - if they can achieve the right regulatory balance.

In petroleum production, operators are always required to properly decommission infrastructure which is no longer required for operations. Indeed, petroleum operators must consider and plan for decommissioning from the very beginning of any operations. In order to even begin the least impactful investigations, companies must convince regulators that they are responsible, technically sound and have plans (as well as access to funds) to restore and remediate the environment in which they will operate. Otherwise, they will not be able to obtain a license to operate and nothing happens.

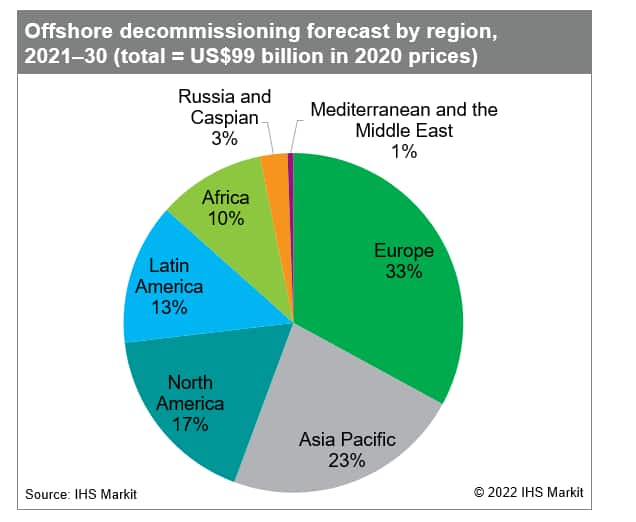

In mature offshore petroleum jurisdictions such as the North Sea and Gulf of Mexico, where production is winding down in many fields, such decommissioning obligations are increasingly falling due. Already, global offshore decommissioning activity has increased significantly over the last decade and is set to grow even further during the coming 10 years. Predicted spending on global offshore decommissioning is way up and is set to increase by orders of magnitude in the coming years. IHS Markit is forecasting such spending to reach almost USD100 billion for the 2021-30 period (an increase of over 200% compared to the previous ten-years).[1]

Figure 1: Offshore decommissioning forecast by region

Figure 1: Offshore decommissioning forecast by region

Leave no trace

Legally, decommissioning entails full removal of installations and remediation of the environment. The North Sea countries, through the Oslo-Paris Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic, have committed to the responsible removal and recycling of redundant platforms. While there may be a possibility in some countries for abandonment-in-place of some structures where this is shown to cause no harm or even provide some benefit (as in the case of the creation of artificial reefs on the US Outer Continental Shelf), the overwhelming regulatory impetus in this area points towards the complete removal and remediation.

The upshot is that in these mature offshore petroleum provinces there is a lot of steel and concrete that needs to come back on-shore for recycling and as such, very significant capital will be required to make that happen. While it is right - and required - that operators plan to make good on their decommissioning obligations, there is a growing realisation that some uneconomic oil and gas assets now present an enticing capital-saving opportunity for players in other industries moving into the offshore.

Money for old (repurposed) rope?

Energy transition imperatives may potentially breathe new life into otherwise moribund assets. As deployment of renewable and cleaner forms of energy accelerates, it is becoming clear that existing infrastructure may present savings opportunities in both time and capital for growing sectors in this energy transition space such as:

Reuse potential will of course depend on the location and condition of the assets and many modifications will likely be required to ensure compliance with applicable standards for their new purpose. In some, perhaps many, cases, reuse will not be possible due to HSE issues arising from the age of installations that cannot be safely or efficiently remedied. However, the potential capital savings for these new energy activities may be considerable and in the case of carbon capture and storage (CCS) any synergies may be pivotal in making the enterprise economic.

CC…Yes, if possible

Building CCS infrastructure is expensive. Where carbon injection into reservoirs is not used for enhanced oil recovery (thereby generating additional revenue from a field) this has been a large stumbling block to adoption of the technology. Upfront capital expenditure for a transport and storage network is relatively high (although once built, the operating costs are expected to be relatively low). It is hoped that the potential reuse of depleted oil and gas reservoirs, onshore and offshore pipelines, compressor stations, injection and monitoring wells and subsea manifolds will go some way to softening the upfront hit.

There is related upside on those installation savings in the shape of potential cost-savings on oil and gas decommissioning obligations which may be shared with, or transferred to future offshore users. With well plugging and abandonment costs representing over 50% of decommissioning expenditure for a field, the possibility to realise further value from those wells as carbon storage injection or monitoring wells will be a welcome opportunity for late-life oil and gas operators.

Not so fast

Whatever the future use, it is clear that there needs to be a regulatory bridge between decommissioning obligations and any infrastructure repurposing. In the North Sea, there are mechanisms being put in place to ensure that such synergies are not missed with potentially useful assets decommissioned before their potential future value has been considered properly. Regulators are seeing the necessity to step in to fill the coordination gap between the various disparate players. For example:

And while the will to capture this opportunity is evident, it is not lost on Regulators that enabling different forms of infrastructure reuse may engender new regulatory issues which require clarity. Issues that have been raised include the following:

Preserving essentially suspended assets to maximise their future potential use will certainly have cost implications for their current operators. While delaying the outlay of final decommissioning costs might be welcomed by some, the terms of any suspension will need to be clarified as this will present an ongoing risk of liability and additional, if comparatively less significant, costs.

Even where infrastructure cannot be feasibly reused, pushing a regulatory pause button on some decommissioning may be an attractive option in any event. Further coordination of decommissioning efforts between fields can bring savings as multiple operators may be able to achieve economies of scale by bundling individual assets into a broader decommissioning campaign.

However such issues may be resolved, it seems logical that a more collaborative ethos across different offshore participants may increasingly be infused into regulatory processes. The UK provides an innovative approach to upstream regulation in requiring operators to consider much broader concerns beyond just their own assets. The OGA recently revised its key strategy and places renewed obligations on operators to act in accordance with the UK's maximising economic recovery strategy. Legislation now explicitly requires operators to considering alternative measures to abandonment or decommissioning such as re-use or preservation.

This kind of facilitative regulatory and policy framework may provide a model for other Regulators in seeking to bring about the potential gains in this area. We would expect further such regulatory developments in maturing oil and gas jurisdictions which may present synergy opportunities of this kind in their energy transition trajectories. IHSM Markit will continue to monitor and provide insight on evolving regulatory frameworks around the world as countries seek to triangulate the obligations of outgoing petroleum producers, the interests of new offshore entrants and the constant imperative to properly regulate environmental concerns.

Learn more about IHS Markit energy transition policy and regulatory monitoring.

[1]IHS Markit, Decommissioning will be the growth sector in the offshore oil and gas industry, 11 January 2022

Posted 26 April 2022 by Benjamin Morel, Consultant Associate Director

This article was published by S&P Global Energy and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.