Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Our Methodology

Methodology & Participation

Reference Tools

S&P Global

S&P Global Offerings

S&P Global

Our Methodology

Methodology & Participation

Reference Tools

S&P Global

S&P Global Offerings

S&P Global

Oct 09, 2023

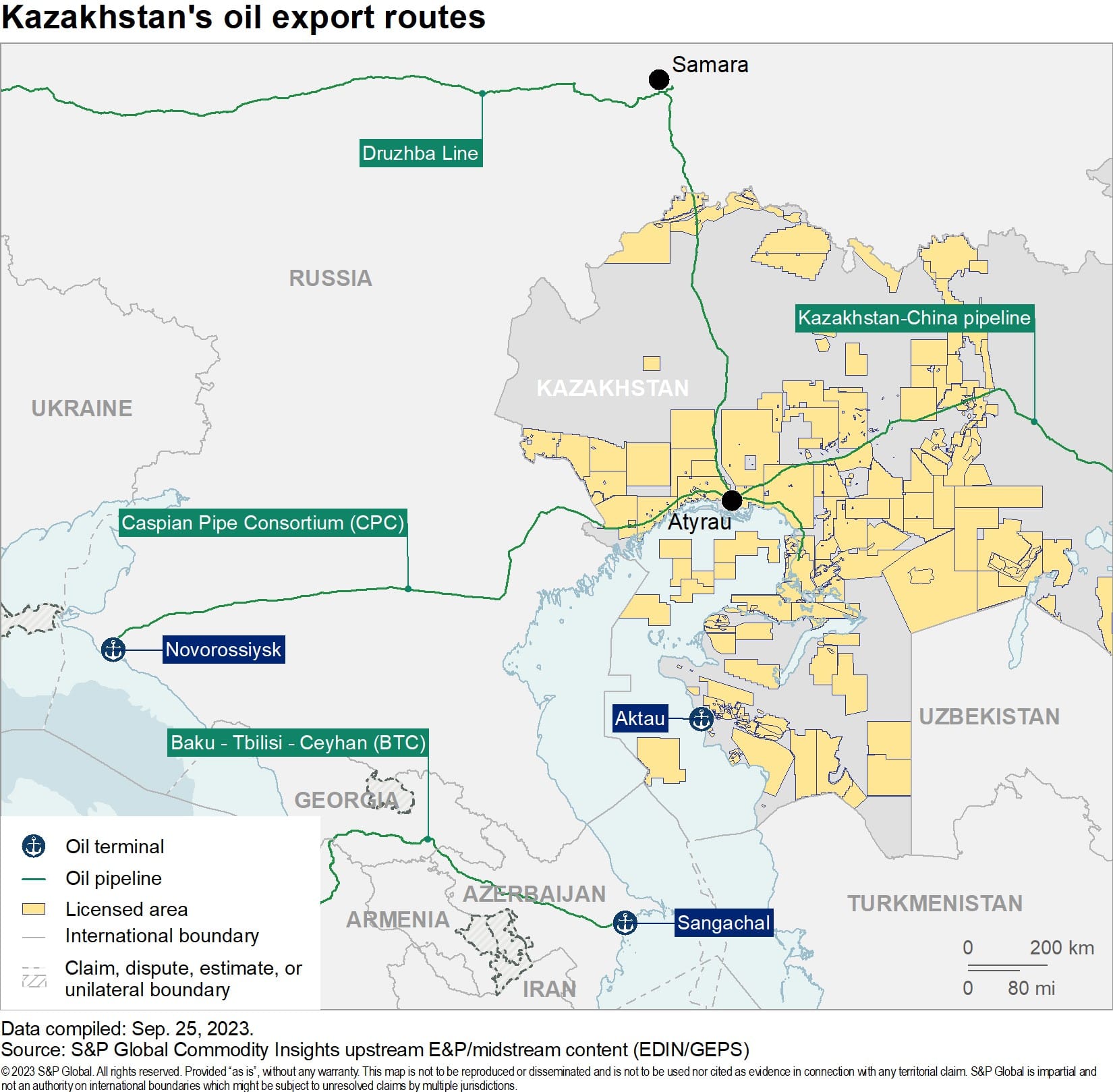

In 2022, Kazakhstan produced 84.2 million tons of oil and exported 64.3 million tons. Of this export volume, 52 million tons were transported through the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), and 8.4 million tons went through the Atyrau-Samara pipeline. Additionally, smaller export quantities were sent via the Kazakhstan-China pipeline system, maritime routes across the Caspian Sea, and a railway route to Uzbekistan. However, these alternative routes accounted for relatively low export volumes. Specifically, 2.3 million tons were transported through the Aktau port, 1.2 million tons via the Atasu-Alashankou pipeline, and only 0.4 million tons by rail. The CPC pipeline constituted up to 80% of the total exports. Nevertheless, due to geopolitical tensions and issues at the Novorossiysk terminal, Kazakhstan is actively exploring alternative export options.

Trans-Caspian route

The most appealing direction is the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline, which reaches the Mediterranean Sea, avoiding the Black Sea waters. The National Company "KazMunayGas" has agreed with the shareholders of the oil pipeline to transfer 1.5 million tons of oil annually. In March 2023, Kazakh exporters started supplying a portion of their products in this direction.

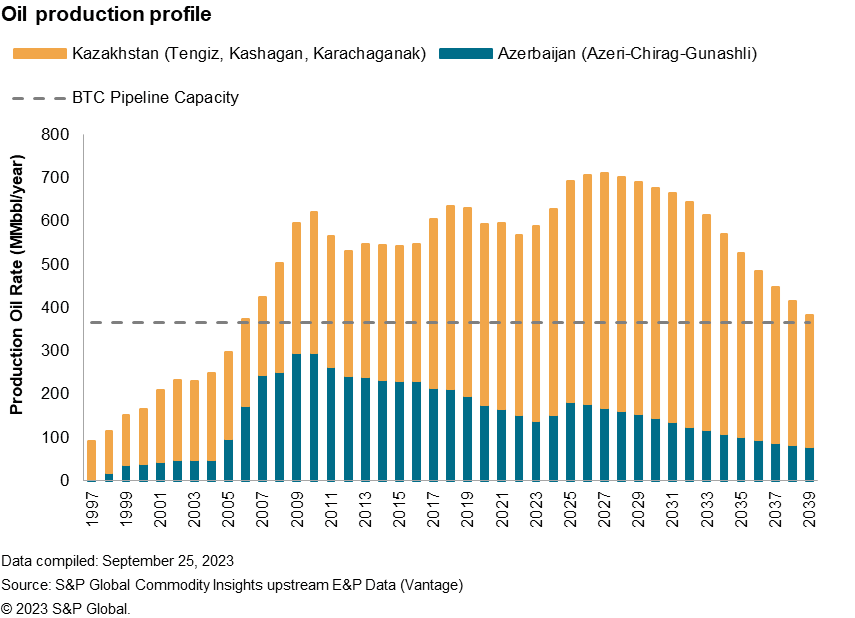

In recent years, due to declining oil production in Azerbaijan, the pipeline is not operating at full capacity, and Kazakhstan could utilize the remaining capacity. However, challenges arise due to differences in oil quality and costs. Azerbaijan exports high-value Azeri Light crude oil, while Kazakh oil is heavier and less valuable. To use the BTC pipeline for Kazakh oil, adjustments to its composition are needed to match Azeri oil's quality. Additionally, Kashagan oil contains sulfur and hydrogen sulfide, requiring extra processing and expenses. Given the relatively high transportation costs via this route, increasing export volumes using the BTC pipeline raises significant concerns about the feasibility.

Currently, only tanker shipments are available through the Caspian Sea. Expanding the Trans-Caspian route would require Kazakhstan to acquire new tankers. However, the Caspian Sea is becoming shallower, and large tankers are unsuitable. Their maximum carrying capacity should be around 10,000 to 12,000 tons. The Caspian Integrated Maritime Solutions company (CIMS) has acquired two new tankers, each with a deadweight tonnage of 8,000 tons. These tankers are set to arrive in Aktau in the autumn of 2023. The combined transport capacity of these two acquired tankers on the Aktau-Baku route will only amount to 800,000 tons per year.

To consider the Trans-Caspian route for oil supply diversification, a comprehensive program to modernize Caspian Sea ports is crucial. Apart from expanding the tanker fleet, this includes increasing the oil loading capacity at the Aktau terminal from its current 12 million tons per year, constructing an oil pipeline linking the Tengiz field to the loading terminals, and conducting dredging operations at the Aktau port to enhance vessel tonnage capacity. These factors significantly increase the cost of oil transportation along this route, potentially exceeding $100 per ton of oil. Even in the most optimistic scenario, it's unlikely to replace the CPC pipeline fully.

Russian transit

Kazakh oil is transported through the Atyrau-Samara pipeline, currently at 70.6% capacity, with a max of 17 million tons per year and actual transport of 11-12 million tons. An expansion project aims for 25 million tons annually. It represents a growth potential of approximately 13-14 million tons annually. Subsequently, the oil can be delivered to Europe via the "Druzhba" system or transported in the direction of the Baltic ports of Primorsk and Ust-Luga or the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk for global tanker shipping.

Germany and others are considering buying Kazakh oil through Druzhba. Initially, 1.2 million tons were planned for 2023, but only 20,000 tons entered in February 2023. By July 2023, KazTransOil had transported 290,000 tons to Germany. In August 2023, Kazakhstan planned to deliver 100,000 tons of oil to Germany from the KPO resources (Karachaganak Petroleum Operating). Kazakh oil will be supplied to an oil refinery located in Schwedt with a capacity of 12 million tons annually. The Druzhba oil pipeline is also the cheapest transportation route. Oil deliveries to Germany through this route cost $29 per ton. But the potential volumes are not so high.

Transporting oil through the Baltic ports, on the other hand, comes at a significantly higher cost. Also, there is no guarantee that the Russian side will have available tankers in the ports for additional volumes of Kazakh oil.

Reorienting oil supplies to Asia

Kazakh oil can be transported through the Atasu-Alashankou route (Kazakhstan-China pipeline), which currently operates at half capacity, primarily with Russian oil (about 10 million tons). The challenge is that foreign companies with Kazakh oil fields prefer selling their products to European refineries due to their investments there. Additionally, China's western regions, bordering Kazakhstan, have their oil production, while the eastern and central areas, with major industries and consumers, favor maritime oil routes. China is also increasing oil purchases from Russia, benefiting from substantial discounts, making it challenging for Kazakh oil to compete.

Conclusion

The existing options for increasing Kazakhstan's oil exports, first and foremost, are incapable of replacing the volumes handled by the CPC pipeline. Secondly, they face significant pricing and infrastructure limitations. Even if all the medium-term plans described above are implemented, the combined increase in Kazakhstan's export capacities would reach 44 million tons per year. This is far below the existing capacity of the CPC pipeline and almost half of the planned 80 million tons per year for 2023.

This article was published by S&P Global Energy and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.