Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

29 Mar, 2021

Massachusetts building electrification backers moved one step closer toward obtaining authority to restrict natural gas use in new buildings with the passage of a new Bay State climate road map.

The act directs the Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources, or DOER, to design a "highly efficient stretch energy code" for new construction that towns and cities can adopt on a voluntary basis. A coalition of climate activists and nearly 60 local governments see the provision as a means of requiring all-electric construction, after efforts to adopt California-style building gas bans failed.

Brookline, Mass., adopted the East Coast's first ban in November 2019, but the Massachusetts attorney general's office struck down the bylaw in July 2020, ruling that state utility law preempts a local government's authority to restrict gas distribution service. Depending on how DOER structures the new stretch code, which "stretches" beyond the minimum code, the state could be poised to grant that authority.

Gov. Charles Baker signed Senate Bill 9 into law on March 26, after initially vetoing predecessor legislation, expressing concern about the stretch code provision's impact on housing affordability. In a press release, his office called the provision "a key component of the administration's Clean Energy and Climate Plan."

Throughout the first year of the electrification push, a handful of towns and cities were at the forefront of the effort, while other communities awaited legal clarity. Following the attorney general's decision, about a dozen cities partnered with sustainability group RMI to form a Building Electrification Accelerator program. In February, participant cities organized a letter to Baker in support of the stretch code signed by representatives from 59 municipalities representing roughly 40% of the state's population.

"That letter was extremely influential, not necessarily for the governor ... but it was to the state legislature, showing the breadth and depth of support for building electrification and improved building performance standards," said Lisa Cunningham, a Boston-area architect and organizer with RMI who worked on the Brookline bylaw.

Stretch code to set state on path to net-zero buildings

Under the act, DOER will work with the Board of Building Regulations and Standards to develop the opt-in stretch energy code that must include, but will not be limited to, a definition of a net-zero building and net-zero building performance standards. The code must comply with the state's greenhouse gas emissions limits.

The act requires DOER to hold at least five public hearings in geographically diverse settings, including rural, suburban and urban areas, as well as at least one community that is underserved or has a high percentage of low-income households. It also directs DOER to consider developing a tiered implementation that would phase in requirements based on building type, uses and load profiles. The state must develop and promulgate the stretch code no later than 18 months from the act's effective date.

The act further directs the state to adopt a program to expand the market for efficient heat pump technology for space and water heating, funded through the Massachusetts Renewable Energy Trust Fund.

Rep. Tommy Vitolo of Brookline and Rep. Kay Khan of Newton initially sought to develop a clean heat standard, but they adapted the stand-alone legislation to work within Senate Bill 9. In a December 2020 interview with S&P Global Market Intelligence, Vitolo said a single opt-in code would marshal the expertise within state agencies for the benefit of all local governments. It would also avoid a patchwork of building electrification codes around the state that could frustrate building developers and trade unions and spark opposition, he added.

Fight over stretch code design likely to follow

Building electrification backers plan to turn their focus to the stakeholder process to ensure the stretch code clearly allows municipalities to restrict fossil fuel use in new buildings and does not broadly exempt any building types. "I think [the legislation] leaves a little bit of wiggle room — maybe a bit more wiggle room than we'd like to see — especially for municipalities that are really pushing for fossil-fuel-free new construction," RMI carbon-free buildings program manager Stephen Mushegan said.

Coalition members also expressed concern that an extended phase-in period could delay towns and cities from implementing the policy for several years. Cambridge City Council member Quinton Zondervan, who has spearheaded efforts to restrict gas use in buildings, said the stretch code created the possibility for his city to mandate all-electric small residential construction by 2022.

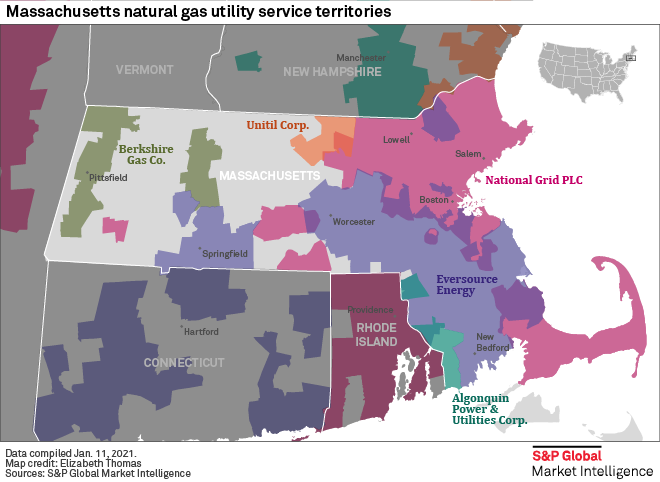

National Grid USA said it applauded the collaboration between Baker and legislators that yielded a stretch energy code that "encouraged a balanced approach to electrification without limiting the use of natural gas." The company believes decarbonizing the state's heating sector requires a portfolio of solutions, including renewable natural gas, National Grid said in an email. It added that electric heat pumps should be paired with emerging technologies like hydrogen, dual-fuel heat pumps and geothermal district heating networks.

NAIOP Massachusetts, which represents major commercial and residential developers and previously warned the stretch code could derail large-scale projects, plans to engage in the stakeholder process. Anastasia Nicolaou, vice president of policy and public affairs at NAIOP Massachusetts, said the group was pleased the act included language allowing DOER to phase-in requirements. "Generally, NAIOP believes that any discussion or policy implementation that seeks to reduce greenhouse gas emissions must include a comprehensive approach that achieves our climate goals without hurting the state's economy, or negatively impacting our residents and small business," Nicolaou said in an email.

Meanwhile, the Massachusetts chapter of the American Institute of Architects and the Boston Society for Architecture wrote Baker in support of the bill.